Teaching and research

Sustainable Feedback

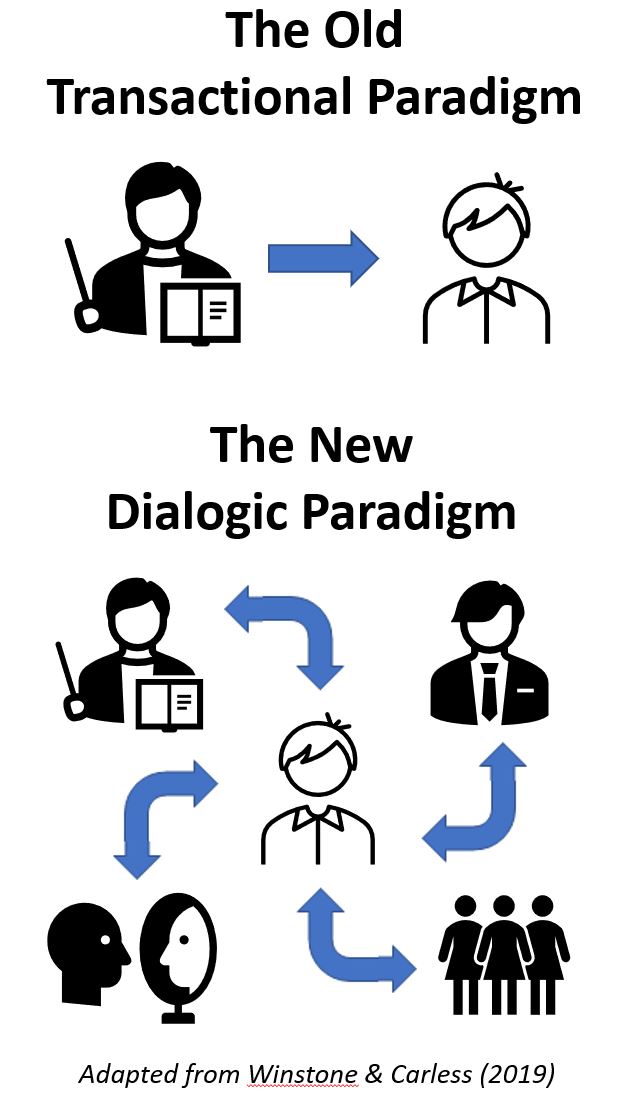

In recent years there have been increasing challenges to the top-down approach of academics ‘giving feedback’ to students. Over-reliance on this transactional approach has the potential to place the student as a passive recipient of feedback, rather than developing students’ skills as an active agent in seeking and making sense of feedback. A newer approach instead encourages the development of feedback literacy by integrating multiple sources of feedback and adopting a multi-directional dialogic approach which more closely reflects the conditions students will face in their post-university careers. The aim of the newer approach is to support sustainable feedback practices where students develop skills in feedback seeking, evaluation, and application that will serve them throughout their careers and support their lifelong learning. This new approach also provides multiple opportunities throughout a course for comments to be made on student work to improve learning. This is key for student understanding of what form feedback can take in your course.

Student Feedback Literacy

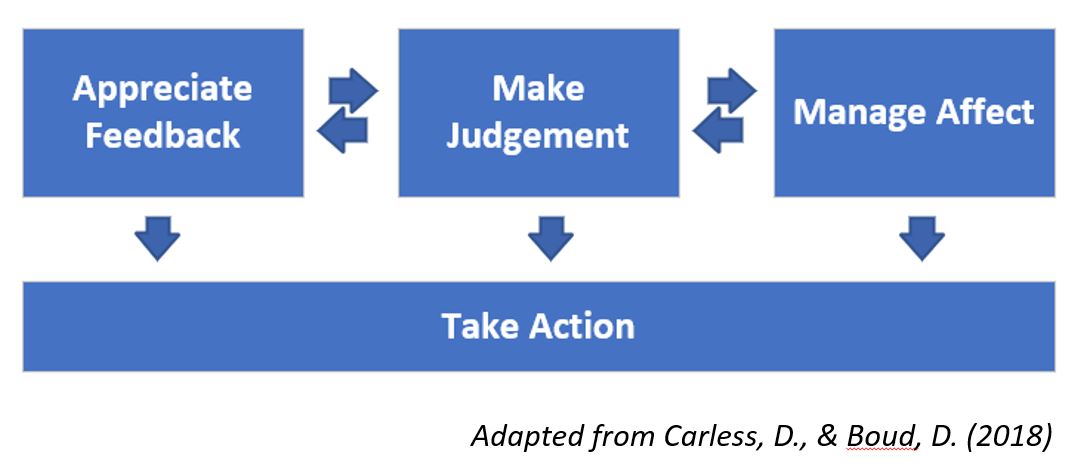

It has been argued that feedback is only effective when it is applied by the student. However there are a number of hurdles that must first be overcome before a student can apply feedback to their future work. Like any academic skill, the ability to understand, make sense of, and apply learning from feedback is a skill that can be developed. Carless and Boud (2018) break down feedback literacy into four interconnected behaviours shown in the diagram below. This shows that in order for students to receive the benefits of feedback they must first have the skills, motivations, and opportunities to:

- Appreciate Feedback – understand feedback information and seek clarification where needed

- Make Judgements – determine the potential for feedback to improve performance

- Manage Affect – manage their emotional response to feedback and take responsibility for action

- Act on Feedback – apply their new understanding to future work produced

Developing feedback literacy in the classroom

Classroom teachers, including our tutors and demonstrators, are in a unique position to develop student feedback literacies. Some of the methods that can be applied in the classroom to develop feedback literacy include:

- Engage with grading criteria – reviewing rubrics in class can help students develop an understanding of what is or was required in an assessment.

- Class discussion of feedback – generalised feedback in class can allow all students to benefit from each other’s approach to assessment.

- Peer feedback – informal review of fellow student’s work can provide benefits to both the reviewer and reviewee. Students receiving feedback can develop skills in receiving and integrating feedback from multiple and sometimes contradictory sources as will occur in the workplace. When providing feedback students benefit from seeing varying qualities of work, and can develop skills in the critical assessment of both their and others’ work.

- Modelling - Tutors and demonstrators can model how they respond to and benefit from the feedback inherent in the academic peer review process or the workplace. Discussions about how to handle frustrations and disappointments, or how to manage conflicting feedback messages can demonstrate that feedback skills are not only relevant to academic pursuits, but relate to all career stages.

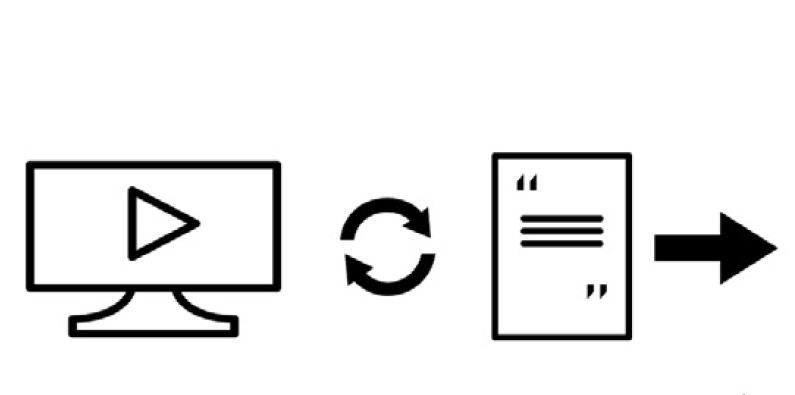

- Explicit Feedback Instruction or Support – students may be provided with guidance on how to interact with the feedback they receive. Winstone and Nash (2016) provide a toolkit to support student feedback literacy, including a glossary to guide students on the meaning of specific academic or disciplinary terms used in feedback, and a flow chart outlining what to do with feedback (pictured below).

Feedback Flow Chart for Students

Adapted from Winstone & Nash (2016)

Designing for feedback

Feedback should be considered in the design of assessments for the course. In designing this process, it is recommended that you consider:

- Authentic Assessment – How well an assignment reflects a real world task should be considered in assessment design. Students will be more interested in obtaining and applying feedback that is directly related to a skill they will apply in the real world.

- Encourage Dialogue – assessments with peer review inbuilt exposes students to varying quality of work while also guiding student self-evaluation. Assessments that have peer review inbuilt, such as observation of peers, or viewing or interacting with work on exhibition (e.g. scientific posters, creative works, etc), can provide this opportunity. Ascertaining student feedback preferences as part of assignment submission can create dialogue by guiding the marker to prioritise feedback effort, while priming students to self-reflect on their work and engage in the feedback as dialogue (Bloxham & Campbell 2010).

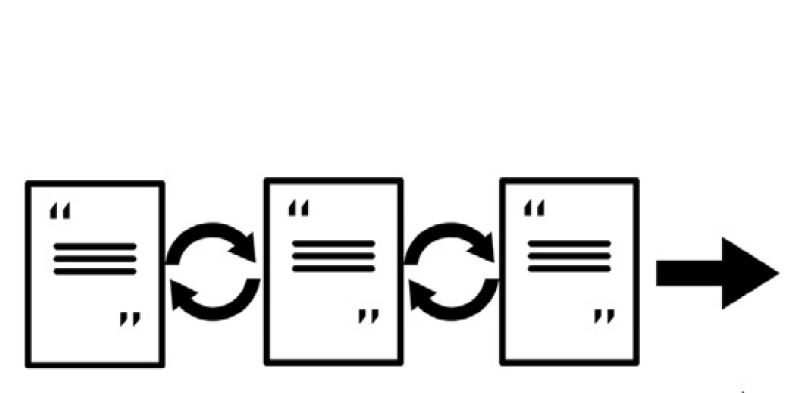

- Opportunity to apply feedback - Where possible students should be given opportunities to apply feedback from early assessments to their performance in later assessments. The format of the assessments need not be the same. As shown below a series of linked assessments can provide opportunities for application, despite being structured across a variety of tasks.

Assessment Task Designs to facilitate update of feedback

| 1. Task Series | Students complete a series of similar tasks (eg. a series of lab reports) where each provides feedback that can be applied to the next task. |

|

|---|---|---|

| 2. Two-Part Tasks | Students complete a first task (eg. presentation) where feedback can be used to inform a second related task (eg. a written report) |

|

| 3. Draft-Plus-Rework | Students receive detailed feedback on a draft before submitting the final assignment. Marks may be awarded for demonstrating how feedback has been applied (eg through reflective submission) |

|

| 4. Pre-Task Guidance | Students engage with rubrics, criteria and exemplars before completing their own assignment. This dialogue with peers and teachers serves as pre-task feedback. |

|

Winstone & Carless (2019)

References

Bloxham, S., & Campbell, L. (2010). Generating dialogue in assessment feedback: Exploring the use of interactive cover sheets. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(3), 291-300. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02602931003650045

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment and evaluation in higher education, 43(8), 1315-1325. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Winstone, N., & Carless, D. (2019). Designing Effective Feedback Processes in Higher Education: A Learning-Focused Approach (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi-org.ezproxy.newcastle.edu.au/10.4324/9781351115940

Winstone, N.E & Nash R.A. (2016) The Developing Engagement with Feedback Toolkit (DEFT) Higher Education Academy https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/developing-engagement-feedback-toolkit-deft

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.