Scientists breed hope for endangered Littlejohn’s frog

For the first time, scientists have successfully bred the Littlejohn’s tree frog (Litoria littlejohni) in captivity. This marks a major milestone in the conservation of the endangered species.

Littlejohn’s tree frog survives only in a handful of small, isolated and inbred populations in New South Wales, Australia.

University of Newcastle conservation scientist, Dr Kaya Klop-Toker, said it was an exciting breakthrough.

“Male and female frogs from the Watagans, in the Central Coast Ranges, were carefully paired in breeding tanks. Two separate pairs bred, producing about 200 eggs each. From these, around 90 grew into healthy tadpoles,” Dr Klop-Toker said.

The success follows years of persistence and refinement by the University of Newcastle team.

“It’s incredibly difficult to replicate the natural habitat in the lab.

“Tadpoles are extremely sensitive, with temperature and water chemistry all needing to be carefully balanced,” Dr Klop-Toker said.

These two clutches mark the first time Littlejohn’s tree frogs have been bred in captivity, representing a vital step forward in their conservation.

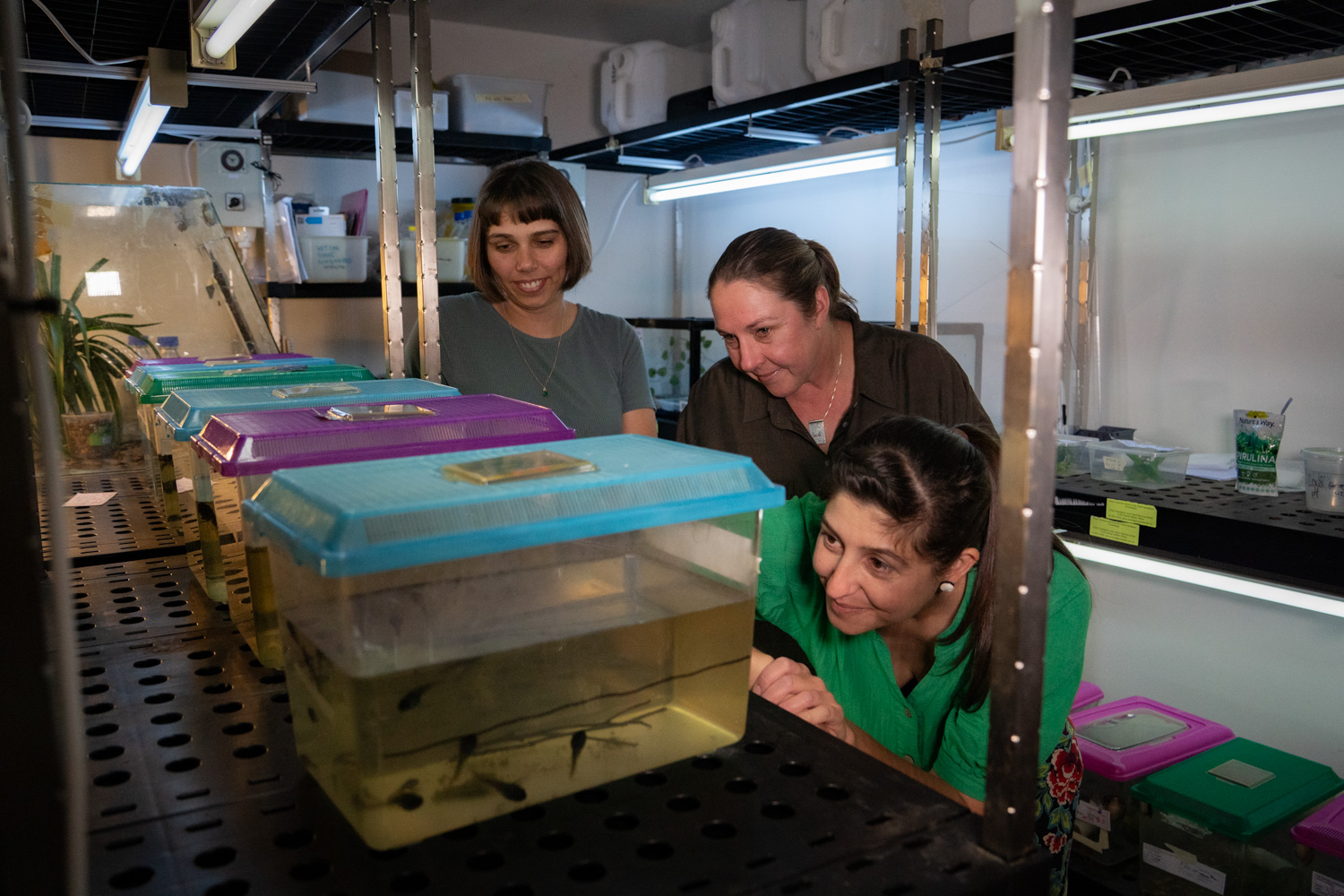

(L-R) Dr Rose Upton, Dr Alex Callen and Dr Kaya Klop-Toker with the first clutch of captive-bred Littlejohn's tadpoles

A world-leading integrated approach to conservation

This captive breeding success is part of a broader strategy that combines multiple conservation actions – in the wild and in the lab – to maximise the recovery of the endangered frog

Conducted through the University’s Centre for Conservation Science, the research forms part of its Amphibian Integrated Conservation Unit.

Assistant Director for the Centre for Conservation Science, Dr Alex Callen, said their focus on integrated conservation work over the past decade had been crucial to success.

“Rather than focusing on a single conservation method, our combined approach creates the best outcome for the species because we can address challenges at both the biological and habitat levels,” Dr Callen said.

“The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recently announced a best practice ‘One Plan’ approach to species conservation,” Dr Callen said.

“This reflects the integrated work we have been doing since 2018, combining habitat creation and manipulation strategies with reproductive biology, conservation physiology and biotechnology strategies.”

‘Aquatic stepping stones’ bridge populations two kilometres apart

Working with NSW Forestry Corporation and NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, the scientists helped create more than 40 new ponds in the Watagans ranges to bridge two populations of Littlejohn’s tree frog.

“We discovered there are two sub-populations of Littlejohn’s, living two kilometres apart.

“By building aquatic stepping stones, we’ve connected frog populations that were previously cut off from each other,” Dr Callen said.

The Amphibian ICU identified areas that were ideal to create breeding ponds.

“Frogs rely on ponds for breeding, and aquatic environments to live in. By creating more pond habitat, we encouraged breeding and provided refuges during drought,” Dr Callen said.

By using genetic analysis, the team was able to prove the habitat corridor did improve geneflow and strengthen genetic diversity in the frog populations.

Threats to survival

Dr Klop-Toker said the Littlejohn’s frog is threatened by disease and habitat destruction.

“New infrastructure development, such as the proposed energy transmission lines in the Hunter, also threaten its habitat, making integrated conservation strategies crucial.

“The Hunter Transmission Line project, which will help support the future use of renewable energy, is currently proposing to clear a 60 m wide corridor alongside the new breeding habitat, with a proposed switching station to be built on top of key breeding ponds.

“This is a difficult situation because we want accessible renewable energy, but if we are breeding animals here in captivity to release back into the wild, we need to ensure that there is appropriate habitat to release them into.”

“The Hunter Transmission Line project is open for public feedback until the 24th of September,” Dr Klop-Toker said.

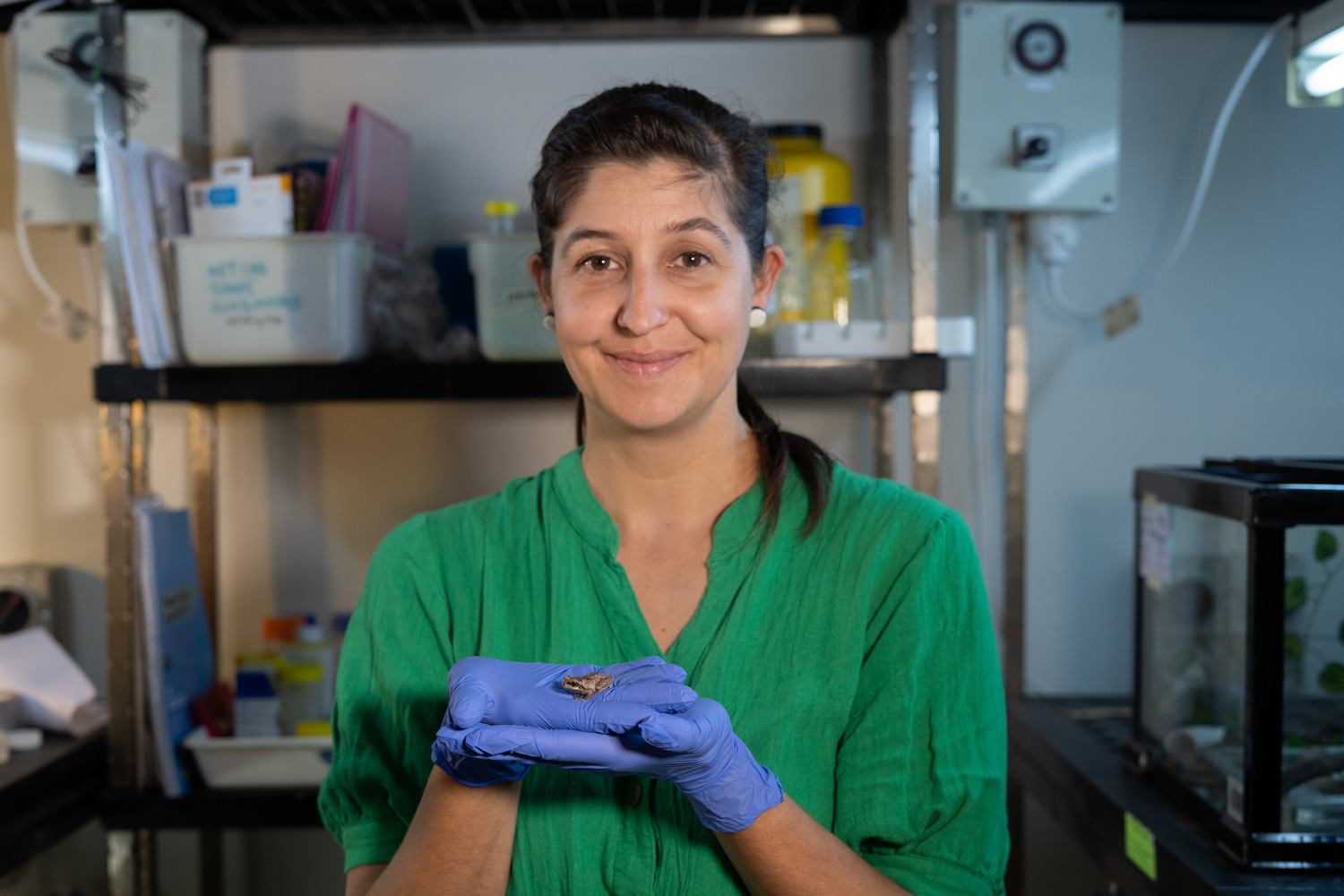

Littlejohn's tree frog. Credit: Krishna Komanduri

Giving frogs a head start

In addition to habitat restoration and captive breeding, the team runs a head-starting program where eggs are collected from ponds in the wild and reared in controlled conditions until they reach froglet stage.

“This gives the eggs a much better chance to reach maturity by shielding them from predators and disease,” Dr Klop-Toker said.

When the frogs are released, it’s important to identify and monitor individuals.

“Unlike with other species of frogs where we can use a tiny microchip to identify individuals, Littlejohn’s tree frogs quickly reject them. Instead, we insert a tiny polymer tag under the skin that glows under UV light and lasts a few days to monitor newly released frogs,” Dr Klop-Toker said.

The team also uses genetic sampling for longer-term monitoring.

“We take genetic samples of our head started frogs, so even years later we can track their contribution to the population,” Dr Klop-Toker said.

Dr Kaya Klop-Toker pictured with a juvenile Littlejohn's tree frog

Restoring lost genetic diversity

DNA analysis forms part of a "genetic rescue" project, aiming to not just increase population size but to restore lost genetic diversity.

The Littlejohn’s tree frog populations are not only small but also increasingly inbred.“This is a dangerous combination for long-term survival,” University of Newcastle conservation biologist Dr Rose Upton said.

Dr Upton is leading research into sperm and reproductive biology using IVF, ultrasound and sperm cryopreservation.

“Sperm cryopreservation has the potential to boost genetic diversity within both captive and wild populations of threatened frogs. It can even help reintroduce genetic diversity that has been lost,” Dr Upton said.

Dr Upton and her team have improved sperm cryopreservation protocols for Littlejohn’s tree frog, and have leveraged IVF to help with the genetic rescue of Littlejohn’s tree frog.

“IVF is a powerful tool – we can combine the genetics of frogs from different populations, without having to remove frogs from their already small groups,” Dr Upton said.

A film by Mhairi Fenton

Contact

- Media & Communications Specialist, Penny Harnett

- Email: penny.harnett@newcastle.edu.au

Related news

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.