Truth Telling: The role of Purai Global Indigenous History Centre in the shaping of an equal future

Let’s take away the buildings, peel back the tarmac, silence the thrum of industry, fill in the tunnels that undermine the City of Newcastle and begin with what was.

Awabakal Country. Cared for and managed by the Pambalong Clan.

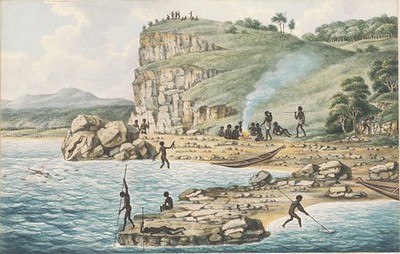

Convict artist, Joseph Lycett’s watercolours and Emeritus Professor, John Maynard’s critique of them provide an accurate perspective of traditional life, pre-contact.

A Worimi man from the Port Stephens area, Professor Maynard’s book, True Light and Shade: An Aboriginal Perspective of Joseph Lycett’s Art provides a critical Indigenous perspective on Lycett’s art.

According to Professor Maynard, Lycett’s depictions of economic, cultural and ritual activities of the First People of Newcastle have become an important source of Australia’s pre-colonial history.

According to Professor Maynard, Lycett’s depictions of economic, cultural and ritual activities of the First People of Newcastle have become an important source of Australia’s pre-colonial history.

“The Pambalong, like all of the Aboriginal clans, lived in a virtual paradise of plenty,” Professor Maynard writes.

“They had the added rich resources of the swamp and wetland areas within their clan territory,” he says referring to the University of Newcastle’s Callaghan campus.

“Their already rich diet of the marine and marsupial variety was supplemented with mud crabs, wild duck, waterfowl and an endless variety of other birdlife.”

Professor Maynard is also the Co-Director of the Purai Global Indigenous History Centre which moved from Callaghan Campus to University House in the City Precinct late last year.

University House in the City Precinct late last year.

While Purai still maintains a close affiliation with the Wollotuka Institute, it has also had a collegiate shift from the university’s Academic Division to the College of Human and Social Futures, under the auspices of Pro Vice Chancellor Professor John Fischetti.

It is fitting that a centre that aims to generate new and ground-breaking interdisciplinary research methodologies for the study of Australian and global Indigenous histories has relocated to a building also steeped in its own history.

Purai’s office now sits in the old Mail Distribution office on level two of the Newcastle Electrical Supply Administration building (NESCA House), now University House and is listed on the NSW’s State Heritage Register.

The building was designed in 1937 by artist-architect Emil Sodersten who was disillusioned with the world’s fascination with skyscrapers.

Sodersten worked alongside a local architectural practice, Pitt and Merewether, to design a building which drew on English perspectives and the streamlined functionalism of contemporary architecture in Europe.

Sodersten worked alongside a local architectural practice, Pitt and Merewether, to design a building which drew on English perspectives and the streamlined functionalism of contemporary architecture in Europe.

Built in the Art Deco style, it was often referred to as “Ocean Liner style” because of the curving on the building’s corners, including the ground floor windows and its clean, simple lines, making it cost-effective to build.

“It shows modernism coming to Newcastle and there was very little modernism at the time,” says architect Barney Collins.

The sandstone used to build the exterior walls was sourced from Wondabyne Quarry, one of NSW’s oldest and most remote quarries at the time, situated at the mouth of the Hawkesbury River.

Not naturally yellow in colour, like much of Sydney’s preferred Yellowstone sandstone, it was artificially coloured which, in part, contributed the building’s increased rate of deterioration.

NESCA House accommodates unique internal features such as travatine floor surfaces (terrestrial limestone deposited around mineral springs), a lovely open staircase, and Italian polished plaster, like a faux marble, on the walls.

There are complex ceilings with up-lighting in spaces like the ground floor’s Demonstration Theatre, popular for cooking shows at the time.

Located next to UoN’s Maker Space, the theatre consisted of three stages, on the outer edges, viewed from one inner seating space constructed on an electrically-driven turntable.

Completed in 1939, just before the advent of the Second Word War, NESCA House was promptly wrapped-up for fear that it would come under attack.

Over the years, this building has supplied electrical light to five Shires, featured in a Superman movie, provided the canvas to a stunning mural and is, most recently, supporting the development of the University of Newcastle’s life-ready graduates.

Senior Manager for the University’s Strategy and Operations (Pathways and Learning Support, PALS), Cheryl Burgess worked for the electricity commission, known then as the Shortland County Council, for 15 years.

Between 1980 and 1986, she worked in the same office as the Purai Global Indigenous History Centre or, the “Distribution/Drawing Office” alongside 15 other young women, who were all employed at the same time.

“I was 16 when I first walked those stairs,” Ms Burgess said, “I got great marks at school but the commission offered a nine-day fortnight and great pay at $68 a week, so I took that.”

During those days, everything was done in-house and Ms Burgess was initially employed as a clerk whose job it was to print out thousands of bills, fold and put them into envelopes.

“Like me, four of those 15 girls went on to work at the Uni,” Ms Burgess said.

Now, what remains of those days are the old signs and the shadowy outlines of old Bundy clocks where workers, like Ms Burgess, clocked in and out.

In 2006, NESCA House was also used in the scene of a bank robbery as “Newhart Federal Bank” in the film, Superman Returns, its grand edifice fitting perfectly into Superman’s hometown of Metropolis, Illinois.

It was the biggest piece Inari had ever attempted and, by mixing spray painting with brush work, her primary aim was to show the subject (rather than the public) her own inner beauty.

“I want to express the feelings that I find in that person,” Inari said.

The stories generated by NESCA House and the Awabakal Country on which it stands are a small part of the history of Muloobinba or Whibayganba, where Nobby’s Lighthouse now stands, or a handful of Awabakal names which comprise the City of Newcastle.

Cultures need these stories to inform and nourish but they also need them to challenge so that people can make sense of the world, understand their past and imagine a better future.

The time to listen to the challenging stories that Australia’s First Nations people have been telling for years is long overdue.

We have all heard the once-celebrated stories of this continent’s colonisation but now it is time to embrace a period of truth-telling where we now hear about what this colonisation brought: massacres, dispossession, surveillance, stolen children, deaths in custody.

Stories also of resilience, survival and success.

Purai is an Awabakal word meaning “the world, earth, land” and, as the only research centre of its kind in the world, it offers the means by which transformative and empowering global Indigenous histories can be built.

Mines cannot be undug. The tarmac has been laid and the buildings, for the meantime, remain.

What can change is our thinking particularly the way we, as a nation, face-up to historical truth, acknowledging what was and, more importantly, imagining what will be.

Contact

- Jacqueline Wright

- Phone: 0428 393 801

- Email: jacqui.wright@newcastle.edu.au

Related news

- Healthy recognition: Dietitian earns prestigious Australian science honour

- Nine Newcastle teams secure $5.4m in ARC Discovery grants to unearth new knowledge

- Nine Newcastle teams secure $5.4m in ARC Discovery grants to unearth new knowledge

- Heart of the problem is short lifespan of disease prevention programs

- University of Newcastle commemorates graduate excellence

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.