Being in lockdown isn’t cricket. Or is it? First year anthropology students learn through play

Playing cricket – Trobriand style – has provided first year anthropology students with the opportunity to have a six-week authentic ethnographic experience.

Originally played face-to-face, this component was ingeniously adapted the following year when the pandemic put staff and students into lockdown by Dr Hedda Askland, A/Associate Professor Daniela Heil and Professor Kate Senior collaborating with staff from the Learning Design and Teaching Innovation unit, Dr Michael Kilmister and Adrian Mereles.

The team have bought these islands in the Solomon Sea, off the coast Papua New Guinea, and their history into contemporary students’ experience through a programme that blends traditional ethnographic research with technology.

Askland says that the team piloted the component in 2019 and tried different ways of integrating participant observation into the course, which to date had been limited.

Teaching ethnography and giving the students a first-hand experience of fieldwork is a challenge in normal times but when COVID hit these challenges were further exacerbated.

“It acted as a real fuel injection. We need to solve this, and we need to solve it straightaway,” she said.

The result is a programme where students are asked to create their own playing field and league for Trobriand cricket after watching a classic 1973 documentary, Trobriand Cricket: An ingenious response to colonisation by filmmaker Gary Kildea and anthropologist Jerry Leach.

The film outlines the adaption of cricket by Trobriand Islanders after it was introduced by British missionaries in an attempt “civilise” them and is used as a springboard to explore ideas of resistance and expressions of identity, belonging and ritual.

“This so-called ‘gentleman’s sport was supposed to replace tribal warfare but, rather than becoming a tool for the colonists, it became a tool for resistance and also ensured some level of cultural continuity within the changing colonial context,” Dr Askland said.

“It really became a space where the Trobriand people were able to maintain inter-ethnic alliances and collaboration and trade.”

“So what we then tell the students to do is … to engage in a similar process,” she said.

Trobriand Cricket: The UoN way

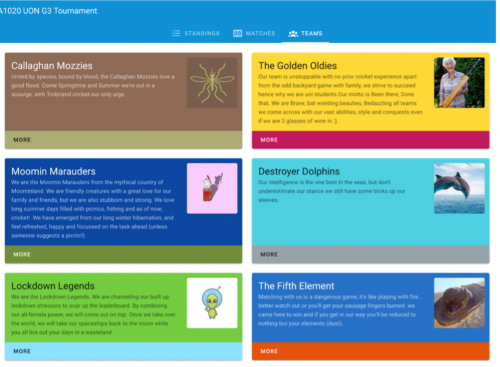

Now in its fourth year, this six-week component is part of a core course with an average enrolment of approximately 200 students across two campuses and online.

Leading up to a final cricket match, students are asked to draw on aspects of identity, ritual, symbols and resistance outlined by the documentary, as they move from “innocent anthropologists” embedded in the field site of their class and opposing teams to “novice anthropologists.”

Leading up to a final cricket match, students are asked to draw on aspects of identity, ritual, symbols and resistance outlined by the documentary, as they move from “innocent anthropologists” embedded in the field site of their class and opposing teams to “novice anthropologists.”

It is designed to reflect the anthropological experience of moving from the stability of what students know and the logic of the university’s conventional learning frameworks, through a period of confusion and unease, to the moment of reintegration.

In the unfolding cricket tournament, lasting six weeks, students study the social structure of their class examining aspects relating to alliances, networks, hierarchies, relations and cultural symbols.

Askland recognises that, at the beginning, students struggle with a lack of direction.

Askland recognises that, at the beginning, students struggle with a lack of direction.

“We purposefully don't tell them too much, because part of the purpose is for them to seek a cultural logic as they will when conducting ethnographic fieldwork in a community to which they are newcomers,” she says.

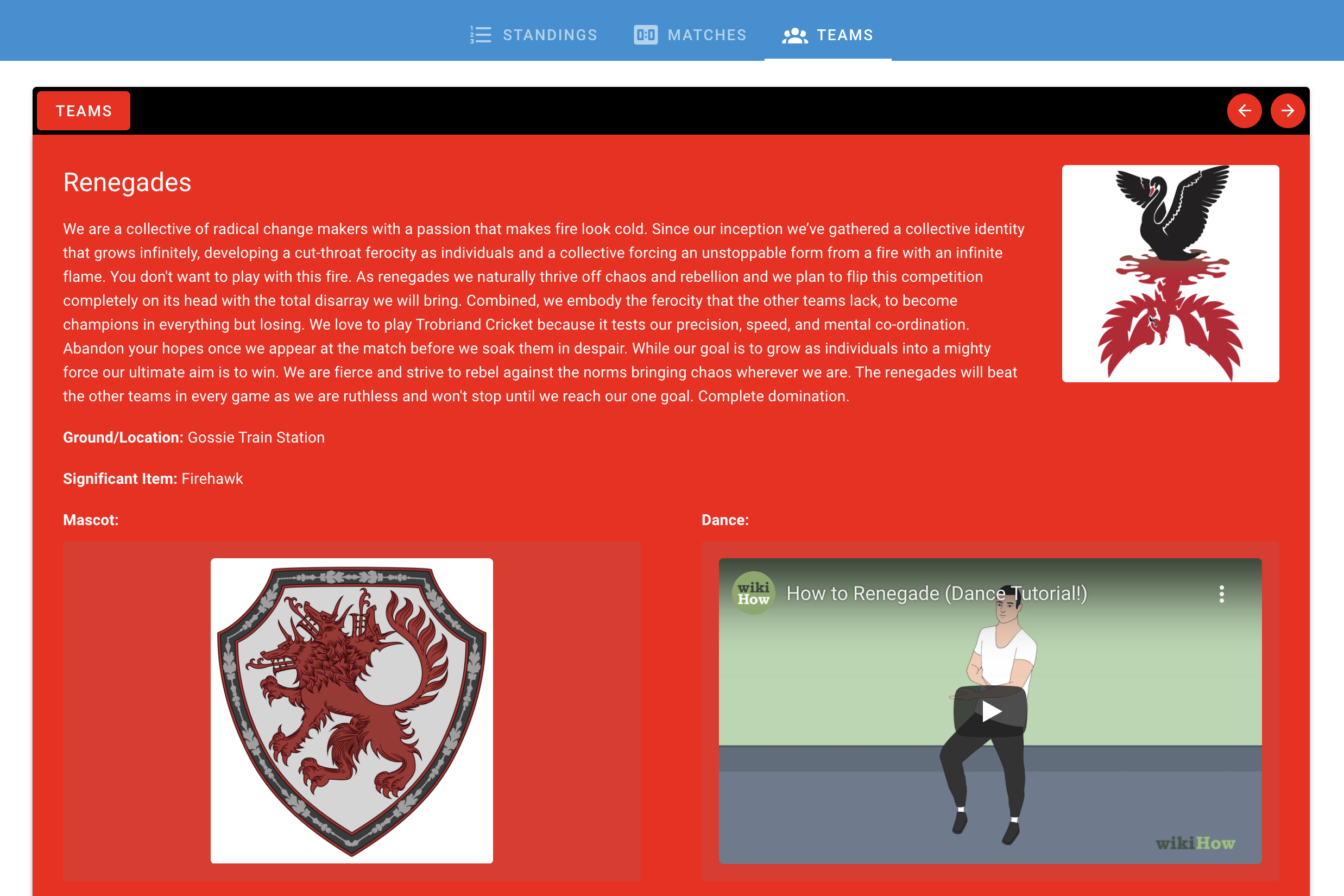

The students are challenged to create an emblem for their team and their home ground as well as devising team colours, a chant, a dance and a symbolic object to represent them.

Askland and her team have developed an array of learning resources, including an app to facilitate this leaning process.

Over the years, the team have included material and online artefacts, such as: cricket bats, a trophy and a hall of fame which both showcases the teams’ material artefacts as well as providing a window for prospective students to get an idea of their previous cohort’s work.

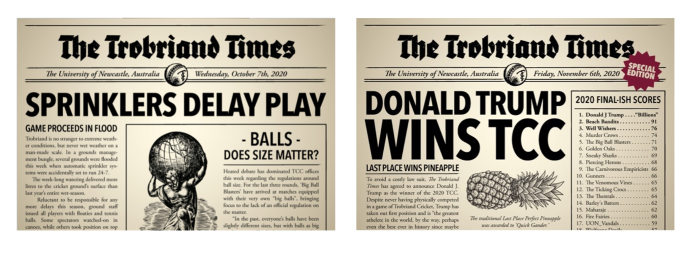

The fictionalised The Trobriand Times features weekly comedic headlines inspired by teams’ actions and is distributed to students through the learning management system, with the aim of generating extra enthusiasm.

There is also a five-minute video that provides context to set exercises, and an app on which the teams display their identity and where weekly matches are organised and “played”.

The app is used as an online fieldwork site and an engagement tool where virtual “matches” are played every week, before the eventual play-off in the final week.

The learning process includes group discussions and posts in addition to writing fieldnotes, which encourage students to observe and reflect, and culminates in a reflective essay about the experience, including the final “match.

An awards ceremony completes the course, where each team votes for their favourites in the categories of best symbol, best dance, best chant, most intimidating and best overall team and best and fairest player (or team).

Students are encouraged to dress up in their team colours and display aspects of their team’s identity recognising this final online celebration as a rite of passage, both in having completed their first anthropology course and concluded and survived a six-week Trobriand cricket tournament.

More than just simulated fieldwork

In developing the component, Askland and her team were acutely aware that many of their students were socially isolated and often very lonely.

“As first year students, they had not yet had time to develop strong cohorts at university and having been in lockdown for months the sense of isolation this can create was even stronger than normal,” Askland said.

“Students are often very reluctant to undertake groupwork, but in this case Trobriand cricket had the effect of bringing people together and building relationships that may extend past the life of the course.”

The fieldnotes certainly reflect this sentiment with one student noting, “We told stories and showed off our pets and plants, it seemed like the first real connection of the semester.”

Askland admits that the student feedback has been very heart-warming.

“They were saying, it was the only thing that brought some joy in the lockdown weeks,” Askland said.

Askland believes that the challenge now is to try how to “future-proof” the component.

“We need to figure out how we can … make it sustainable without the level of involvement from the technical staff that we currently require … advancing it into its next iteration,” she said.

This involves a level of coding expertise from academic staff as well as sandboxing an alternative app, a cybersecurity practice designed to prevent threats from getting on the network.

According, to Askland the extra work is absolutely worth it, and she and her academic team are looking forward to the next big “bash”.

“I would say that it’s the best thing I've ever done in my teaching career,” she said.

Contact

- Jacqui Wright

- Phone: 02 4921 7408

- Email: jacqui.wright@newcastle.edu.au

Related news

- Nine Newcastle teams secure $5.4m in ARC Discovery grants to unearth new knowledge

- Nine Newcastle teams secure $5.4m in ARC Discovery grants to unearth new knowledge

- University of Newcastle commemorates graduate excellence

- Community collaboration takes flight in bird opera workshop

- Community collaboration takes flight in bird opera workshop

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.