Ngukurr to Newcastle: The best ‘from little things, big things grow’ story

Elder and Aboriginal activist Vincent Lingiari, Singer Ted Egan, and a 1960s University of Newcastle’s linguistics student, Nona Harvey all crossed paths with a Nunggubuyu man from the Northern Territory called Dexter Daniels. They described him variously as him as “stand-out”, “a very imposing figure” with “film-star looks”, “austere and very focused”, “clearly a leader who had lots of respect”. Although, none knew him well, Dexter Daniels changed their lives.

So why was he buried in an unmarked grave at Ngukurr, a very remote Indigenous community in the Northern Territory’s Arnhem Land, and known by his own community as another old man?

To begin to answer this question, we need to step back in time to 1999 and join the University of Newcastle’s Co-Director of Purai’s Global Indigenous History Centre, Professor Kate Senior, before she was a co-director and professor, beginning her PhD journey in anthropology at Ngukurr Community.

One of the first things she did when she moved to Ngukurr, 750kms southeast of Darwin, and home to about 1000 people, was to attend a funeral, of an “old man” with her new colleague Daphne Daniels.

Jump forward 21 years and Professor Senior makes a surprising discovery in the Merv and Janet Copley Collection held at the University of Newcastle’s Auchmuty Library.

Merv and Janet Copley were Novocastrians who played a significant role in the development and expansion of the Newcastle Unionist Movement from the 1940s to the early 2000s.

As keen amateur historians, the couple were heavily invested in recording the history of the world around them, and this collection provides a snapshot of the events occurring in their everyday lives.

Lives that foreshadow a community’s on-going pursuit of justice, equality, and recognition.

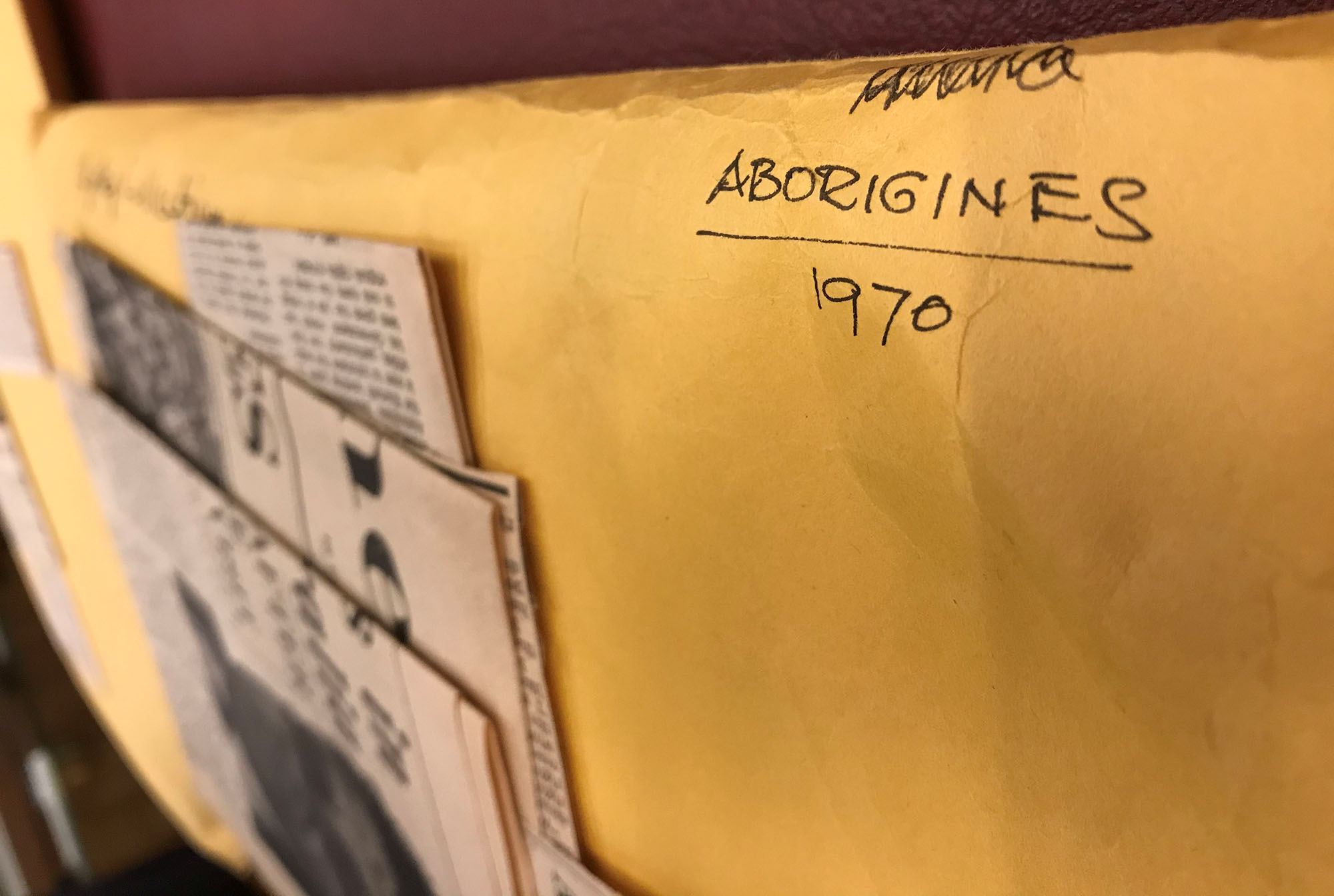

Buried in the archive, in an envelope marked “Aborigines 1970”, Kate found multiple newspaper clippings about people from the community of Ngukurr, where she had worked as an anthropologist for many years.

The clippings sketch out an extraordinary story of a man who put his life on the line and worked extensively to raise awareness about Aboriginal workers’ rights, equal pay and land rights on national and international platforms.

That man was Dexter Daniels.

The story emerging from this archive has reinvigorated people’s understanding of this “old man”, both in his own community and the Newcastle community in New South Wales.

It has also attracted three-year Australian Research Council funding to make sure Dexter’s efforts are not forgotten.

From Ngukurr to Newcastle: Exploring the activism, impacts and legacy of Dexter Daniels explores the intercultural connections between Ngukurr and Newcastle, particularly the strong association and support from the Newcastle trade unions who raised money to support this fight for equality and encouraged their members to recognise and engage with Indigenous Australians challenging racial and economic oppression.

In collaboration with Kate’s Ngukurr colleague and Dexter Daniel’s niece, Dr Daphne Daniels, this project also works to reconnect the archives to people and communities.

By bringing this material back to the community, Daphne feels she can now properly honour the memory of her uncle.

“Like my family before me, I am now a senior leader in Ngukurr. In all that I do, I try to honour my ancestors respecting past and present, and work together with other leaders of the seven tribes to create a safe, strong, vibrant and sustainable community for future generations,” she said in her Honorary Doctorate speech at the University of Newcastle in 2022.

But the Ngukurr to Newcastle project doesn’t stop there.

Harnessing a swag of creatives – playwrights, musicians, visual artists and writers – the project aims to retell the story of Dexter Daniel’s leadership and vision to the communities of Ngukurr, Newcastle community and the rest of the country, reinstating him into the national narrative.

This creative adaption of academic research enables findings to be more accessible to broader audiences in its exploration of how the course of history can be changed and why a regional centre became a hub for Indigenous activism and awareness.

Kate’s serendipitous finding in the Copley Archive is not just one-off.

Now in its second year Ngukurr to Newcastle researchers have discovered more surprising connections.

The Vincent Lingiari Connection

Dexter grew up on Ngukurr Community (or Roper River as the missionaries called it then). In the 1960s, the community was particularly inaccessible with deeply corrugated dirt roads and two river crossings to negotiate.

It’s important for the reader to consider how difficult it was to navigate country like this without 4-Wheel-Drives. Without telephone coverage or portable refrigeration. Little to no petrol stations. Scant resources. A few shillings. If you were lucky.

It’s important to remember this, because the obstacles that Dexter experienced fighting the good fight for his people make this story all the more extraordinary.

Communication was by word-of-mouth, letter or telegram. The roads were rough, even by Aboriginal standards, the trucks that drove on them old. With leaf springs and drum brakes all around, they were usually loaded up to the hilt with provisions travelling hundreds of kilometres, at little more than 60kms/hour.

There is also this – the Northern Territory was called the “Far North” then, by people living on the South-eastern Seaboard.

To the majority of Australia’s population the Far North, in the 1960s, was as far away as a fairytale.

The trouble with fairytales is that nobody quite believes that they are real. But the story that is about to unfold is as real as it gets and, as Dexter predicted, “very big”.

Playwright of the Dexter Daniel’s story, Brian Joyce believes that, while the infamous Gurindji Strike was significant, this story extends beyond Wave Hill to a collective struggle that endures as a living framework for justice.

In 1960, Dexter drove away from the strict discipline and segregated dormitories he was forced to sleep in in order to access a western education.

He navigated that deeply corrugated road, negotiating those river crossings to work firstly as a stockman at Oenpelli Mission before joining his brother, Davis Daniels, in Darwin where he lived on Bagot Reserve.

Dexter worked for Trans Australia Airlines (TAA) washing planes and also as an orderly with his brother at Darwin Hospital.

Dexter’s brother was also active in the recently established Northern Territory Council for Aboriginal Rights, travelling to Kenya in 1964 to study its independence struggle with another Ngukurr activist, Phillip Waipuldanya Roberts.

Dexter stayed at home in Darwin organising marches and mass meetings to raise awareness of Aboriginal Rights issues.

The May Day March, acknowledging International Workers’ Day, made newspaper headlines in 1964 who reported, “400 Aborigines March in Darwin; Make History”. Men, women and children marched, mothers nursing babies.

In 1965, following the failure of the Commonwealth Arbitration Commission to immediately grant industry award wages to Aboriginal stockmen, Daniels began a series of trips to Victoria and NSW to raise awareness of the rights of Aboriginal workers.

In August 1965, he became the first Aboriginal person to win a trade union election for the position of organiser for the North Australia Workers Union (NAWU).

The following year, he was elected president of the Northern Territory Council for Aboriginal Rights.

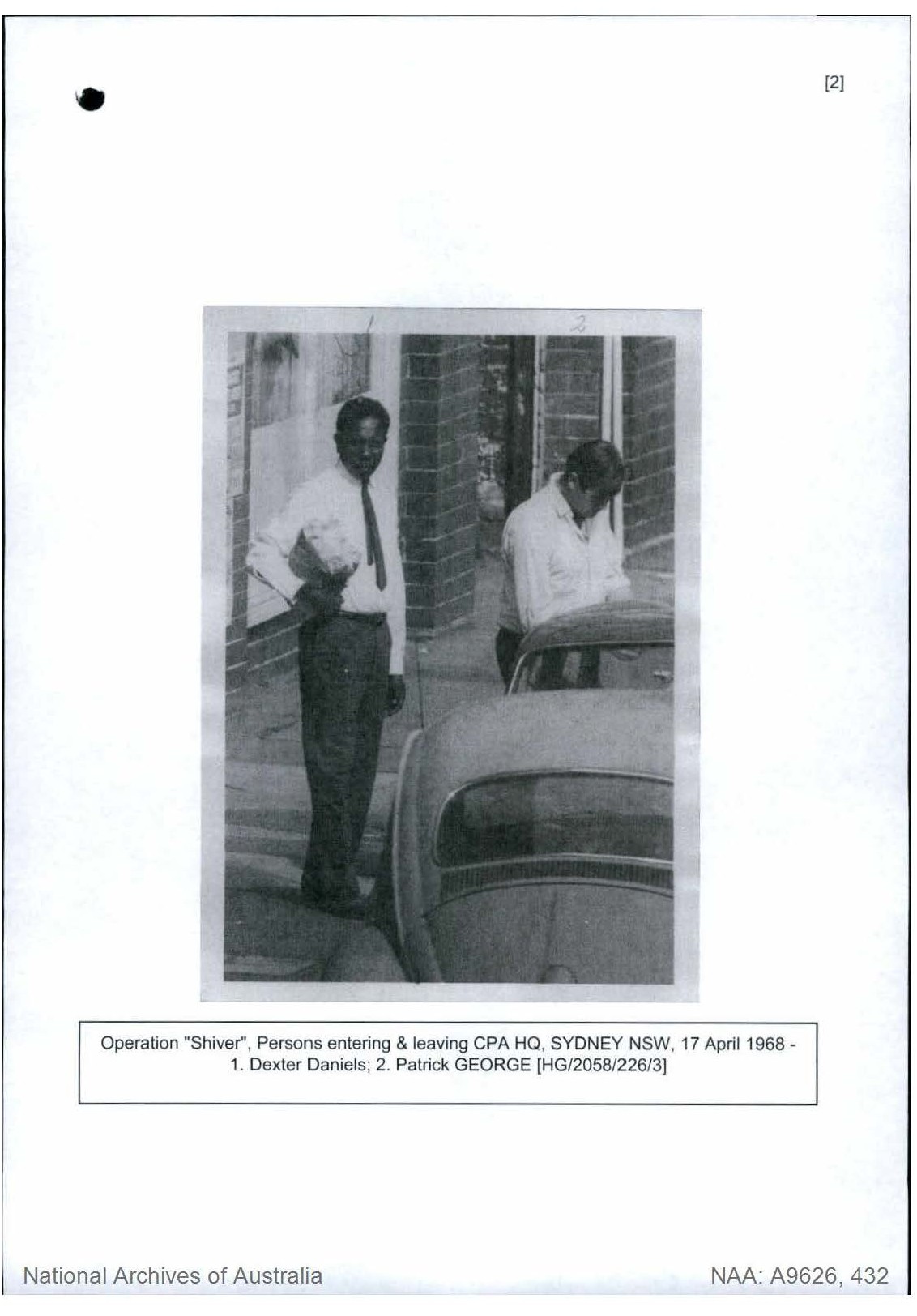

As former union organiser, Daniels was closely aligned with the Australian radical left and supported by members of the Australian Communist Party (ACP).

This association, in part, may be one of the reasons Dexter’s story has been wiped from the national consciousness.

It was certainly the reason he amassed a three-volume Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) file, complete with pictures.

In the intense anti-communist atmosphere of the Cold War, a person associated with the ACP, or the “Red Peril” as communism was known in the 60s, implied disloyalty to Australian democratic values, national security and industrial peace.

Dexter was well on the way to ticking one of those boxes.

Australian author, Frank Hardy, was a member of the ACP and began working closely with Dexter after Dexter had called on him wanting to see “the bloke from Sydney who writes books.”

Frank interviewed Dexter in 1967 and this tape-recorded piece is held in the papers of Frank Hardy at the National Library of Australia,

In the interview, Frank, in his strong Australian vernacular, quizzes Dexter about how he began the first Aboriginal strike.

Dexter’s responses are eloquent and unhurried. It’s a voice that encourages the listener to lean in.

We learn that the first strike was not the Gurindji Strike at Wave Hill, made infamous by Kev Carmody and Paul Kelly’s From Little Things, Big Things Grow ballad, but at Newcastle Waters, 500kms east of Wave Hill in the Barkly Tablelands.

While this strike was the first in the Northern Territory, it was not the first in country.

That was in the Pilbara, north-western Western Australia (WA) in 1946 when around 800 Aboriginal pastoral workers across 25 different stations walked-off in an act of defiance against the state’s Aborigines Act 1905.

But if the Far North was a fairytale, WA was another country, a country beyond the Commonwealth.

About half-way through the interview with Frank, Dexter recalls meeting an old man in the hospital.

“... and I said to him ‘Old man where you from?’ and he said, ‘I come from Wave Hill.’ I said, ‘Yes, well, I might take a trip to Wave Hill one day. I might see you there at Wave Hill.’

That old man was Gurindji man, Vincent Lingiari, who staged the Gurindji Strike or Wave Hill Walk-Off.

Dexter asked Vincent how much the Wave Hill Cattle Station Manager was paying the Aboriginal stockmen.

“Only $6 AUD a week and rations; raw flour, tea and sugar ... salt beef,” Vincent had answered. This was less than one fifth of the minimum wage paid to white stockmen at the time.

Dexter visited Vincent at Wave Hill, a cattle station owned by the British company, Vestey, shortly after this meeting in his role as NAWU President.

At this stage in the interview, Frank Hardy interrupts Dexter saying that he remembers meeting Dexter and fellow trade unionist, Brian Manning on the road on their way to the striker’s camp in the dry riverbed of the Victoria River all those years ago.

They had stopped and chatted before going their separate ways. “I remember,” Frank says to Dexter in the interview, “as you went over the hill you waved, and I wondered what was going to happen to you. I was a bit worried about you that day.”

Frank had good reason to be worried. Brian Manning recounts the journey in his 6th Vincent Lingiari Memorial Lecture in 2022 and describes the road from the Willeroo turn-off to the striker’s camp as a “horror stretch”.

His small Bedford truck was overloaded with three 44 gallon drums of fuel and stores to feed 200 stockmen and their families. “We crawled along most of the way between 15 and 20 m.p.h [miles per hour].”

This would not be a one-off journey.

Frank continues in the interview, “The next day I didn’t hear any news. But two days later I heard on the radio 200 people on strike at Wave Hill!”

Frank then asks Dexter how it all unfolded.

Dexter tells him that he met Vincent at the airstrip where they spoke of the strike staged a few months ago by the stockmen at Newcastle Waters Station, 500kms east of Wave Hill in the Barkly Tablelands.

“He [Vincent] said to me, ‘We waited and wanted to see you for a long time.’”

They drove to the storekeeper’s quarters at Wave Hill where it was quickly discovered that the stockmen were at the races.

This didn’t deter Dexter who told Vincent that it was important to get the stockmen to stop work as soon as they came back.

He told Vincent, “Get the stockmen together and tell them what I tell you. As soon as you get all the stockmen together, stop work and send a telegram [to Darwin] and I’ll be back here to bring more rations ... I’ll come down for sure.”

“We’ll have to do this the same way as Newcastle Waters people did. We must stick together. This is not just a strike. This is very big. This thing will spread all over the world. People will listen to this and read about it in the newspaper.”

Vincent fought the battle on Gurindji Country, leaving Dexter to fight for them in the South.

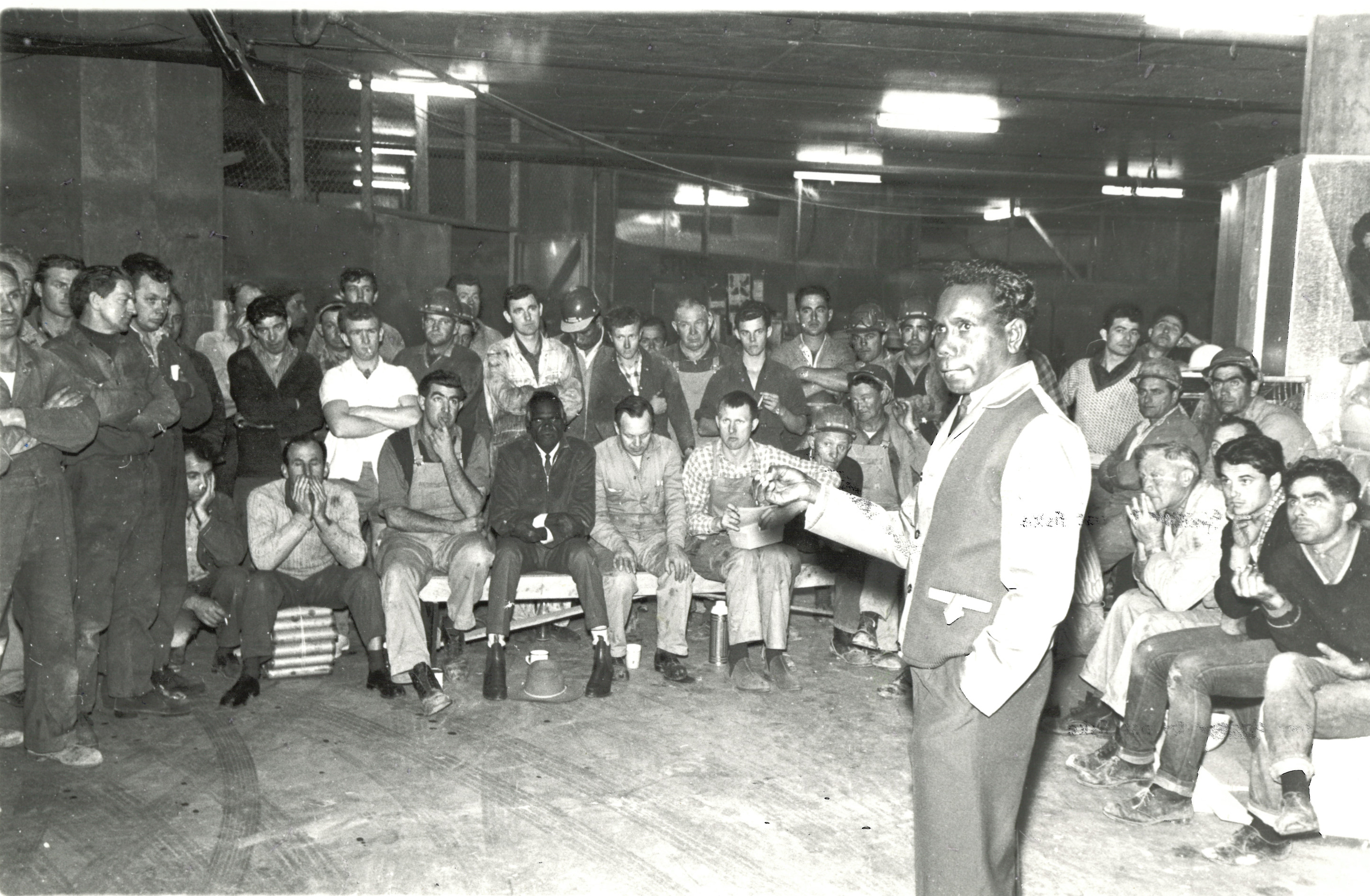

According to the Australian Trade Union Institute, Dexter, along with fellow-activist Lupna Giari (also known as Captain Major), conducted a speaking tour sponsored by the Building Workers Industrial Union and Actors Equity, addressing sixty meetings in just over a month.

Dexter spoke to Trades Unions and their members, university students and citizen and church groups.

There were demonstrations, arrests and mass meetings. Collections were made and politicians were pressured to act.

This advocacy not only raised public awareness, it also helped to raise finances and establish a nation-wide boycott on goods and services manufactured by the Vestey Group.

Donations from the south assisted striking workers and their families to set up a permanent camp at Daguragu (Wattie Creek), the camp established during the strike by Vincent Lingiari, stockmen and their families on Gurindji ancestral homeland.

They helped build fences and stockades for horses in preparation to run their own cattle station one day.

When the Vestey Group flew in scab labour to Wave Hill Station, the Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union employees refused to process beef transported to slaughterhouses by the company.

Dexter was dead right, it was reported by the national press and, importantly, the Gurindji Strike eventually led to the formation of the Northern Territory’s Aboriginal Land Act 1978, changing the course of Australian History.

As Brian Joyce writes Dexter had the ability to reframe “Aboriginal issues as national concerns” as w ell as linking “local protest to national legislative reform”.

ell as linking “local protest to national legislative reform”.

Dexter’s niece, Dr Daphne Daniels, is proud of her Uncle’s work.

“Uncle Dexter was a powerful leader. Although he was only educated through the mission to read and write, he knew how important education was. He looked for people with knowledge and skills to work with,” Daphne said.

“He was particularly interested in people with strong written communication skills, and he enlisted the writer, Frank Hardy, to help him organise the Wave Hill Walk-Off and raise interest in the southern states about the rights for Aboriginal people.”

“Together they were a powerful force,” she said.

Without support from the South, the Gurindji might never have been able to make it through the nine years it took to have a portion of their homeland returned to them.

Daphne talks about the impact Dexter had on Frank Hardy who wrote about the Gurindji Strike in the book, The Unlucky Australians.

“It has never been lost on me that people remember Frank Hardy, because he had the power of the written word, but no-one, until now, remembers Dexter Daniels,” she said.

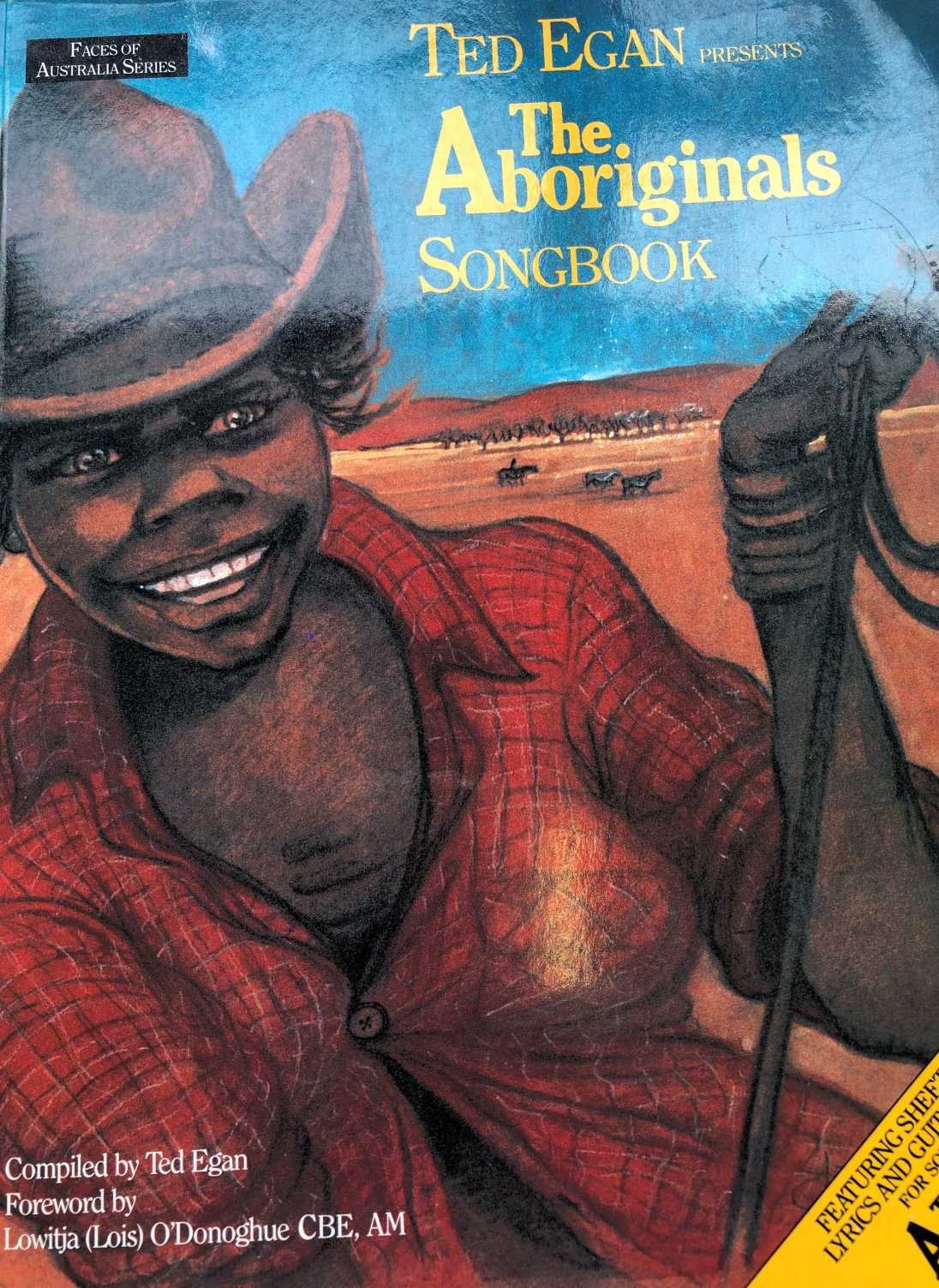

The Ted Egan connection

Musician and author, Ted Egan, first heard of Dexter’s work in 1966, when he was working as Head Teacher at Angurugu (Groote Eylandt).

“I knew and admired Dexter Daniels,” Ted declared in an email to the project’s Chief Investigators, Professor Kate Senior and Dr Ray Kelly, in June 2024.

“I heard about the strike at Newcastle Waters that was inspired by Dexter and Captain Major, then the Gurindji walk off from Wave Hill.”

“I, like most white locals considered that they would be starved back into servitude within a couple of weeks. Not so,” he writes.

Ted acknowledges that Dexter, along with other members of Dexter’s family, were instrumental in maintaining the longevity of the strikes by driving long distances to deliver rations to striking communities which they supplemented with traditional food sources.

He names other supporters such as the Chairman of the Darwin Branch of the CPA, Brian Manning, and Robert Tudawali Wilson who was cast in the lead male role of Jedda, a full-length colour motion picture filmed in the early ‘50s.

By the time Ted met Dexter face-to-face he was working as a research assistant for the Australian National University (ANU).

The position was offered to Ted by Dr Harry Cole (Nugget) Coombs, the then Chancellor at ANU and Chair of the Council for Aboriginal Affairs, established soon after the 1967 Referendum where nearly 91 per cent of Australians voted to amend the Constitution, making Indigenous Australians citizens.

Harry had known of Ted’s moral struggle in his previous role as the North East Arnhem Land District Officer when the mining of bauxite was taking off.

In his role, Ted had personally witnessed the dubious tactics of the government and the mining company when engaging with the Yolngu people.

“The government intended to be totally, arbitrarily on the side of the mining company Nabalco [North Australian Bauxite and Alumina Company], rather than the local Aboriginals, betraying them in the process,” he said.

“I contemplated resigning, but fortunately Dr Coombs ... spotted my dilemma and created a job for me.”

Ted became acquainted with Dexter Daniels and the role he played supporting the Gurindji people at Daguragu (Wattie Creek).

“He certainly put his life on the line in pastoral circles that were violently opposed to the notion of land rights,” Ted wrote.

“I never came to know Dexter Daniels on a personal level, but I admire the role he played in the overall land rights campaigns.”

Ted was lucky enough to be the one to tell Vincent Lingiari of the impending victory in 1973.

He recalls that day vividly, especially the drive back to Katherine. “I thought about my involvement and decided that it was time for gadiya [white people] like me to step aside,” he said.

“I stopped the car, wrote a three-line letter of resignation on the bonnet of the car, posted the letter at Katherine and decided that I would make a living composing and singing songs about people I admire.”

Ted Egan went on to write the Gurindji Blues and later, after Vincent’s passing and with his family’s permission, Old Vincent.

“Quite a few of my songs are about great First Australians,” he admits.

Ray Kelly remembers the Gurindji Blues with fondness. “The only record I owned as a teenager was Gurindji Blues, and I played it constantly,” he said.

“It was an important entry point for me into the project ... the combination of story and song is a powerful educational tool. I wish this has been used as the basis for teaching in schools.”

The Nona Harvey connection

Nona Harvey was studying linguistics at the University of Newcastle (UoN) when she first met Dexter in May 1968, not in Newcastle, but at Roper River Mission (Ngukurr).

How Nona got to Roper River in the first place is a story that points to Dexter’s increasing influence through strategies designed to gather a nation-wide support-network.

Nona was the working as the local director of UoN’s ABSCHOL, one of the few nationally constituted bodies which raised money for university scholarships for Aboriginal people.

When ABSCHOL began broadening its focus to support the Aboriginal Land Rights movement, it sent Nona, and three other students from Sydney University on a “fact-finding mission” to learn more about the living conditions of Aboriginal people on cattle stations and the role of the Welfare Department in their lives.

On the 22nd of May in 1968, four students, Nona and three male ABSCHOL students from the University of Sydney, piled into VW Bug and drove over 8,000kms to undertake this task.

They got caught in floods at Winton and had to truck the car on a train for part of the way.

“Stopping at a roadhouse in Katherine to eat, we noticed the front-page article on the NT News titled ‘Southerners Coming to Help Aborigines Invade Towns’. When we looked at an accompanying cartoon we saw four students on a ‘bandwagon’ and realised we were the ones being referred to!” Nona recalls in an interview with Purai’s Cultural Liaison Officer, Angelina Joshua, recorded for the Ngukurr to Newcastle project.

Nona and her compatriots knew then that they were facing something serious. “There was a lot of antagonism in that article, even paranoia about these ‘southerners’,” she said.

“This jolted us out of our naïve complacency, and we knew we would have to proceed strategically.”

After visiting their only Darwin contact, they decided to split into two pairs.

One pair would travel with the Welfare Branch of the Northern Territory Administration (or “Welfare” as it was known as at the time), as planned. The other pair would accompany Phillip Roberts, the then President of the Northern Territory Council for Aboriginal Rights, on his routine health-check of various Aboriginal communities in the Far North.

“The idea was to try and talk to as many Aboriginal people as possible, find out their perspective on things,” Nona said.

Nona vividly recalls the clandestine nature of the tour with many detours made to avoid notice, and, at times, greeted by men with rifles at gates ordering them to turn back.

Nona’s few days with Dexter Daniels at Roper River involved detailed discussions about wide-ranging issues from implementing Indigenous language programmes to the wages, conditions and treatment of Aboriginal people working on cattle stations.

Nona remembers Dexter as one of “several impressive leaders at the community.”

It is fifty-seven years since Nona embarked on that trip and, on reflection, she now understands how Dexter cleverly framed the striking Aboriginal stockmen in a way that unions and working non-Indigenous Australians could relate to and be more likely to support.

“So Dexter came in and saw this equal wages thing could be a wedge, maybe. A wedge, a strategy, to get the attention of the white community,” Nona said.

“He was able to frame the problem in a way that white people could relate to.”

It was clear to Nona, however, that the strike was much more than fighting for equal pay, it was about land and being able to retain and maintain their own customs, Lores and traditions.

This understanding is reflected in a report Nona wrote on her return.

In it she details what she had seen and heard and this sparked a flurry of media activity including a television broadcast.

The journey to the Far North and what she had learned from Dexter Daniels and other Aboriginal people sparked a life-long collaboration with Indigenous Australians.

When asked about Dexter’s legacy, Nona answered, “I’m his legacy if you like and all the other people that worked with him that he managed to get onboard.”

“Once you see something you can’t unsee it and I’ve been obsessed for the rest of my life with trying to, where I can, support this slow but inexorable movement to improve Aboriginal Rights,” Nona told Angelina at the conclusion of the interview.

Angelina, a Warndarrang woman from the Yugul Mangi tribe and Daphne’s niece is from Ngukurr Community and also studying linguistics at Newcastle University just like Nona did, all those years ago.

She agrees whole-heartedly with Nona and, in a film about the project, narrated by Angelina in her first language Kriol says, “A nimin luk dis oulman, imin libu bigiswan stori” [Even though I didn’t meet this old man, he left a great legacy].

The first time she heard Dexter’s story was in Ngukurr when her Auntie Daphne gave a presentation during NAIDOC week and she wondered why he had been forgotten.

Apart from Dexter’s association with the CPA, there is also the inaccessibility of western archives to consider.

As Angelina explains in the film, “en sambala blekbala ma numu sabi hau ba gaji det ma enjing” [and some Aboriginal people don’t know how to get hold of these things].

Angelina admits that learning this “brabli pauwaful wan” [properly powerful one] story has been good for her because she now understands how and why she is paid equally.

Part of her inspiration for making the film is to raise awareness in her own community about this transformative leader in Australia’s social justice landscape and the power of collective action rooted in justice, equality and recognition.

“If yang pipul la Ngukurr irri dijan stori, dei gin olsou bi impauwad en inspaid laik mi. Yu garra gidjap if yu sabi im rait jaslaik det olaman” [If young people at Ngukurr heard this story, they could also be empowered and inspired like I am. You have to stand for what you know is right. Just like that old man did].

This story isn’t done

These connections sketch out a story, but the story isn’t finished yet.

There’s a play to be written and performed at Ngukurr, Newcastle and the Darwin Festival.

There’s a digital archive to be created which preserves the material the team find, making it accessible to future generations, regardless of who they are or where they live.

Articles and an illustrated book in Kriol to be written and published.

Collaborative storytelling between the Ngukurr Community members and artists and Newcastle school students, trade unions and University of Newcastle historians.

This is how to breathe life into a story that refused to be buried.

This is how to tell the truth and multiply those stories, keeping them alive.

And story by story we move forward as a nation.

It really isn’t that hard.

Contact

- Jacqueline Wright

- Phone: + 61 2 4055 1082

- Email: jacqui.wright@newcastle.edu.au

Related news

- Advancing Human-Agent Collaboration Through Agentic AI

- Open Research Newcastle Launch: Free Access to University of Newcastle Research

- Long-spined sea urchin surprisingly not on the menu for large fish

- Twenty years of ResTech: Celebrating collaboration between Ampcontrol and University of Newcastle

- University experts part of new network to reduce reliance on animals in research

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.