Research uncovers the historical experiences of the earliest global domestic workers

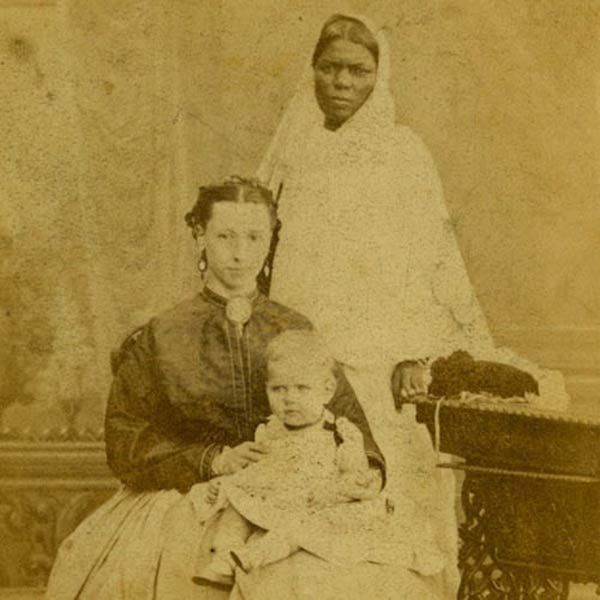

A new research project will bring to life the experiences and histories of the world’s first travelling global domestic workers, the Indian Ayahs and the Chinese Amahs who were employed by colonial families during the period of British colonialism.

Ayahs and Amahs: Transcolonial Servants in Australia and Britain 1780-1945, brings together prominent historians from Australia and the US to conduct internationally collaborative research on the transcolonial origins of global migrant domestic work. University of Newcastle historian, member of the Centre for 21st Century Humanities and expert in domestic service and colonialism, Professor Victoria Haskins, is leading the project and joins with Dr Claire Lowrie from the University of Wollongong and Professor Swapna Banerjee from Brooklyn College of the City University of New York.

Professor Haskins said the project aims to understand and articulate the historical connections between colonialism, carework, and labour mobility as related to female domestic care workers from India and China.

“Accompanying colonial families along circuits of empire between Australia, Asia, and the UK over two centuries, the Ayahs and Amahs were extraordinarily mobile women. By exploring the historical experiences and cultural memories of these earliest global domestic workers, the project aims to illuminate a broader transcolonial history of domestic work.”

Victoria said the Indian nursemaid, or Ayah, occupies a cherished place in the imaginary of imperial and colonial histories.

“Individual recollections of British colonisers in South and South-East Asia have been compiled into the one abiding childhood memory of the devoted native nursemaid.”

Ayahs first emerged as a distinctive occupational group in India with the arrival of British wives from the late eighteenth century, to become the mainstay of childcare work for the British in India.

“In Singapore, Indian and Malay Ayahs were also present during the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. By the 1930s, however, childcare in the Straits Settlements, and in Hong Kong, was the domain of Chinese Amahs,” she said.

But these Indian and Chinese women workers were not only employed in households in South and South-East Asia. They also accompanied British families, in considerable numbers, across oceans between Asia, Europe, and Australia. And as they journeyed, the cultural symbolism of their role was also transported across and between nations and colonies.

“Their cultural representations, as exotic emblems of empire, were as mobile as the workers themselves.”

The project will make a major historical contribution to international scholarship on domestic work, colonialism, and gender while adding significant new knowledge to Australian histories of labour and migration in global context.

“There are continuing resonances of this rich and little-known history of mobile domesticities for present-day debates in Australia, Britain and Asia, on the legacies of empire and colonialism,” Victoria said.

The project is expected to result in several publications and a website, plus offering social and cultural benefits by advancing our historical understanding of the entangled cross-cultural relationships that have shaped our world today.

Related news

- Advancing Human-Agent Collaboration Through Agentic AI

- Translating compassion: a linguist's commitment to social inclusion

- From Research to Reality: New Algorithms Revolutionise Geotechnical Design

- Scientists find a fast, new way to recover high-grade silver from end-of-life solar panels

- University of Newcastle’s I2N takes out top honours

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.