Birabahn Cultural Trail

WALK-DISCOVER-TAP-LEARN

The Birabahn Cultural Trail on the Callaghan campus is a scenic bush walk where you can gain historical and cultural knowledge of the long association that Aboriginal people have with the University of Newcastle.

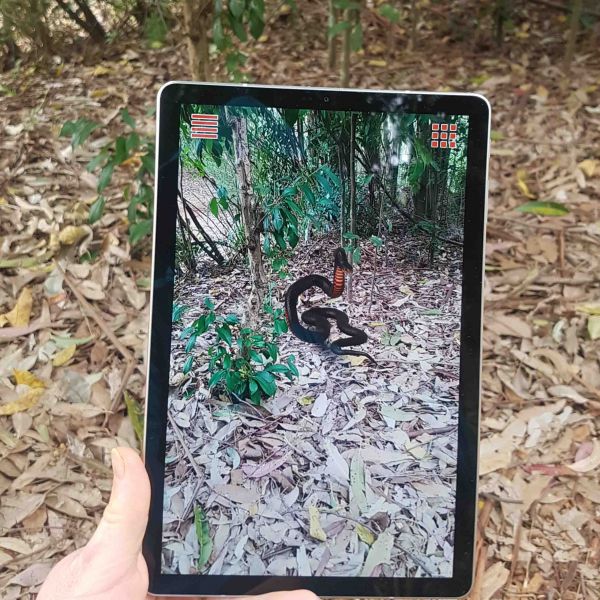

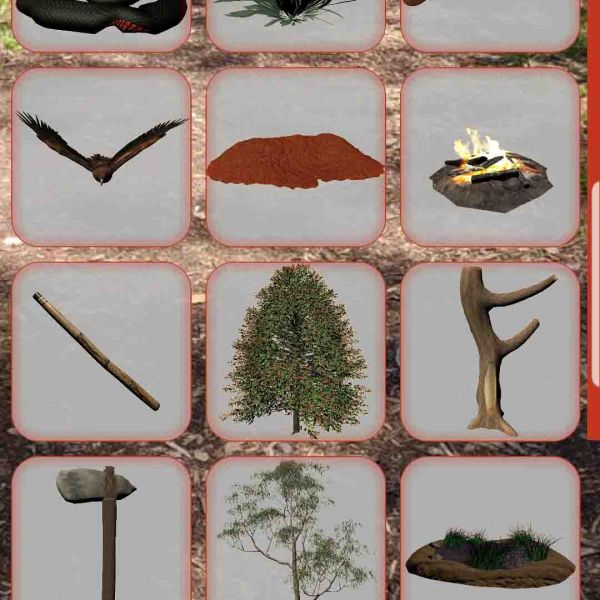

This application brings the trail to life with an abundance of hidden virtual features along the way for you to discover. The objects represent native flora, fauna, handcrafted objects and the four elements of earth, water, fire and air all within the natural environment – ready to be explored and uncovered.

The trail provides learning opportunities detailing the lifestyles and cultural practices of the Pambalong people who have occupied the landscape, living in balance with the wetlands, swamps and Hunter river.

The application features a badge collection system: Once the user has found all the objects, they unlock a completion badge.

Download the app to start exploring now!!

Available on Android and iOS (Augmented Reality)

Baiame the Creator moved across the land, developing the landscape, giving life and lore to men and women and other aspects of the environment.

Commencing on the pathway between the Chancellery and the Shortland Union Building on the Callaghan Campus of the University of Newcastle you can take a leisurely 100 metre walk amongst the bushlands of the Pambalong Clan of the Awabakal Nation. The walking trail will lead you to the Birabahn Building which houses The Wollotuka Institute.

In undertaking this scenic bush walk you will gain historical and cultural knowledge of the long association that Aboriginal people have with the University of Newcastle – Callaghan Campus site.

Campus map showing trail location.

Special thanks to Professor John Maynard for his research contributions on signposts 1 – 3 along the Birabahn Cultural Trail.

Interpretative Signage Panels

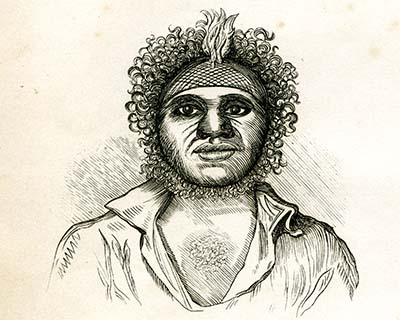

In the early decades

of the nineteenth century a local Aboriginal man was afforded the very

significant name – Birabahn. Birabahn also known as John M'Gill to the

Europeans, was a leader of the people known today as the Awabakal. His name

translates as the "eaglehawk" a much-revered totem of the people. He

was a gifted guide, tracker, teacher, singer, dancer and interpreter. He died

on the 14 April 1846.

In the early decades

of the nineteenth century a local Aboriginal man was afforded the very

significant name – Birabahn. Birabahn also known as John M'Gill to the

Europeans, was a leader of the people known today as the Awabakal. His name

translates as the "eaglehawk" a much-revered totem of the people. He

was a gifted guide, tracker, teacher, singer, dancer and interpreter. He died

on the 14 April 1846.

Birabahn was an Aboriginal man of high degree who today is recognised as possibly the greatest Aboriginal scholar of the 19th century. Probably born around 1800 somewhere near Mu-lu-bin-ba (Newcastle) Birabahn had been taken by the British to Sydney whilst a young boy and assigned as a servant at the Sydney military barracks. He learned to speak English fluently and had a good working understanding of the colony.

What a remarkable and gifted individual this Aboriginal leader must have been. It was he who had the foresight to relate the language to the missionary Reverend Lancelot Threlkeld in such a meticulous manner over 180 years ago. In 1839 James Agate visiting Threlkeld's mission at Bah-tah-bah on the shores of Lake Macquarie recorded a glowing testimonial to Birabahn:

He was about middle size, of a dark chocolate colour, with fine glossy black hair and whiskers, a good forehead, eyes not deeply set, a nose that might be described as aquiline, although depressed and broad at the base. It was very evident that M'Gill was accustomed to teach his native language, for when he was asked the name of anything; he pronounced the word very distinctly, syllable by syllable, so that it was impossible to mistake it. Though acquainted with the doctrines of Christianity and all the comforts and advantages of civilisation, it was impossible for him to overcome his attachment to the customs of his people, and he is always a prominent leader in corroboree and other assemblies.A broker between two cultures over a divide of seismic proportions, Birabahn remains to this day an inspirational guide for future generations of Aboriginal and non-Indigenous Australians, on how to conduct cross cultural relations based on respect and equality for all.

The traditional custodians of the land that occupies

the Callaghan Campus of the University of Newcastle were the Pambalong people.

The Pambalong lived in a virtual paradise of plenty. They had the added rich

resources of the swamp, wetlands, river and lake areas within their clan

territory. Their rich diet of the marine and marsupial variety was supplemented

with mud-crabs, wild duck and waterfowl.

The traditional custodians of the land that occupies

the Callaghan Campus of the University of Newcastle were the Pambalong people.

The Pambalong lived in a virtual paradise of plenty. They had the added rich

resources of the swamp, wetlands, river and lake areas within their clan

territory. Their rich diet of the marine and marsupial variety was supplemented

with mud-crabs, wild duck and waterfowl.

The area which encompassed the land of the Pambalong stretched from Newcastle West, extended along the southern bank of the Hunter River (Coquon), west through Hexham (Tarro) to Buttai and across to the foothills of Mount Sugarloaf (Keemba-Keemba) to the northern tip of Lake Macquarie and back to Newcastle West. The country of the Pambalong was known as Barrahineban – a 'bright place to live'. This was an extremely rich land-holding, laden with all the resources necessary for an abundant and richly rewarding lifestyle. Food was plentiful and variable throughout the year. The seasonal productivity ensured a balanced diet, which was also controlled by a totemic system of food selection at various stages of life.

Although there was no order of rank amongst them it was quite apparent that strict rules were in force and the young men gave undivided obedience to their elders. – Horatio Hale, 1846

The Traditional Pambalong University

Aboriginal people, not unlike university students, were expected to attain various stages of knowledge through initiation and ceremony before full graduation to adulthood. There were restrictions and regulations over articles of food and some commentators noted the strict protocols of control governing these processes:

The youth are not allowed to eat fish, or eggs, or the emu, or any of the finer kinds of opossum and kangaroo… As they grow older, the restrictions are removed, one after another; but it is not till they have passed the period of middle age that they are entirely un-restrained in the choice of food. Whether one purpose of this law may be to accustom the young men to a hardy and simple style of living may be doubted; but its prime objective and its result certainly are to prevent the young men from possessing themselves, by their superior strength and agility, of all the more desirable articles of food, and leaving only the refuse to the elders – Hale, 1846.

Clearly Aboriginal people of the region had established an aged care pensioners program! The effectiveness of such control is clear:

The nature and object of the institution appear to be everywhere the same. Its design unquestionably is, to imprint upon the mind of the young man the rules by which his future life is to be regulated; and some of these are so striking, and, under the circumstances, so admirable, that one is inclined to ascribe them to some higher state of mental cultivation – Hale, 1846.

The impact of the British occupation in 1788 at Port Jackson and the discovery of Newcastle's fine harbour (Mulubinba) by Lieutenant John Shortland in 1797 was the catalyst for the destruction of thousands of years of Aboriginal connection with their land. The European introduced diseases had a catastrophic affect on people who had no immunities to diseases like cholera, smallpox, influenza, measles and venereal disease.

Disease was not the only reason for the sharp decline in the Aboriginal population. Reverend Threlkeld from his Mission on the shores of Lake Macquarie wrote of the atrocities committed against the Aboriginal population: 'A large number were driven into a swamp, and mounted police rode round and round and shot them off indiscriminately until they were all destroyed.'

The termination of the mission has arisen solely from the Aborigines becoming extinct in these districts... The thousands of Aborigines... decreased to hundreds and have lessened to tens and the tens will dwindle to units before a very few years they will have passed away – Threlkeld, 1841.

But Aboriginal people survived and a Pambalong presence in the local area managed to continue in varying degrees, selling fish and honey to the settlers and trading for tea, sugar and tobacco. Some of these people continued with the old ways of moving and travel in looking for means of subsistence. This meant that they looked for seasonal work and places of better opportunities for their families. In the early 1930's Aboriginal people had moved back into the Lake Macquarie district to work on the construction of railway lines.

One area in

particular, at Waratah, had a large Aboriginal population. This area became

known as Platt's estate. A former Depression camp, dozens of Aboriginal families

lived and remained there for decades after the end of the Depression.

One area in

particular, at Waratah, had a large Aboriginal population. This area became

known as Platt's estate. A former Depression camp, dozens of Aboriginal families

lived and remained there for decades after the end of the Depression.

In fact Aboriginal people occupied areas of the future University of Newcastle site as late as the early 1960s. Reporters were surprised to find in the bush-land people living on the creek and wetlands. Under the orders of the Newcastle City Council nineteen Aboriginal people were removed from their shacks on the site in 1963. Through the efforts of the Newcastle City Council, the University, the Department of Education, the Crown Solicitor and the Aborigines Welfare Board some eighteen months later these people were relocated and housed.

Twenty years after Aboriginal people were removed from living on the University of Newcastle site in 1963 Aboriginal people returned with the establishment of Wollotuka.

Wollotuka commenced its operations in 1983 as a support program for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students on what was then the campus of Newcastle College of Advanced Education (NCAE). The program not only survived the years of change – when NCAE became the Hunter Institute of Higher Education and subsequently amalgamated with The University of Newcastle – it thrived.

Growing bigger and

stronger throughout the 80's and 90's Wollotuka outgrew a number of different

office spaces and expanded its operations. In April 2002, the first students

and staff moved into the unique building which you can see on this site. The building, called Birabahn in honour of

both the eagle-hawk totem of the Awabakal and the Awabakal scholar by the same

name, was developed to incorporate aspects of Indigenous practices

and culture to present staff, students and community with a warm familiar

environment.

Growing bigger and

stronger throughout the 80's and 90's Wollotuka outgrew a number of different

office spaces and expanded its operations. In April 2002, the first students

and staff moved into the unique building which you can see on this site. The building, called Birabahn in honour of

both the eagle-hawk totem of the Awabakal and the Awabakal scholar by the same

name, was developed to incorporate aspects of Indigenous practices

and culture to present staff, students and community with a warm familiar

environment.

The spirit of Birabahn the eaglehawk is reflected in the design of the building. An aerial view reveals the roof span as the wings of the eaglehawk outstretched and soaring over its traditional lands.

The official opening was seen as an important milestone in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander education and was celebrated in October 2002 as part of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Festival.

The building's surrounding native plant landscaped gardens and ponds were constructed with the assistance of Aboriginal staff engaged through Yarnteen Aboriginal Corporation in Newcastle.

Wollotuka, now named The Wollotuka Institute centralises all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activities of the University into one operational and strategic body to ensure a culturally supportive and productive learning environment within the areas of teaching and learning; research and innovation; student engagement and experience; community engagement; and staff employment and development.

The Wollotuka Institute now operates out of the three main campuses of the University - Callaghan (Awabakal Country), Ourimbah (Darkinung Country) and Port Macquarie (Biripai Country).

You are welcome to peruse a more comprehensive history of The Wollotuka Institute which is displayed in the downstairs corridor of The Birabahn Building.

The Nations upon whose traditional lands the University of Newcastle and The Wollotuka Institute are located is respected and honoured thereby maintaining a pride in place and custodian responsibilities and obligations.

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.