Kristen McSpadden

When I began my studies at the University of Newcastle, I never imagined that I would travel to remote coral reefs, pilot underwater drones and work alongside fishers on the Great Barrier Reef. What started as a slight obsession with the ocean has evolved into a research career focused on understanding and protecting the complex marine ecosystems.

The sea is an unpredictable and, at times, unforgiving place — yet it supports entire communities’ livelihoods, global food security, and connects nations. This paradoxical environment is essential to life on Earth, from the air we breathe to the food we eat. Whilst transport and fisheries are easily quantified in economic terms, it is equally important to value the ecological functions of the sea as well as the cultural and community connections it sustains.

For me, a career in marine science is about learning where, how and why. It’s about making science fun and accessible and includes all perspectives — from Traditional Owners and local communities to fishers, policy makers and other fellow researchers.

I learned the foundations of marine science and gained valuable hands-on experience through my undergraduate degree program at the University of Newcastle, where I completed my Bachelor of Science in 2020. My Honours research taught me the importance of asking the right questions and paved the way for a career in research. I began my PhD mid-2022 at The University of Newcastle, where I have been working to understand the population dynamics of sea cucumbers on the Great Barrier Reef, in collaboration with Macquarie University, James Cook University, Griffith University, and GeoNadir, funded by the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.

Sea cucumbers are conspicuous marine invertebrates that typically live on the sea floor, consume quantities of sediment, and excrete clean sand through a process known as bioturbation. Functioning like vacuum cleaners of tropical reef environments, they support the health of benthic habitats. While sea cucumbers are intrinsically valuable for the ecosystem services they provide, they are also a lucrative export, known as běche-de-mer or trepang. Historically, sea cucumber fisheries were small-scale, and concentrated mostly in the Southeast Asia, where they were used in Chinese pharmaceuticals and ceremonies. Since then, sea cucumber fisheries have expanded globally, with some species fetching over $500 USD per kilogram of dried product.

Image credit: Dr Vincent Raoult

Image credit: Emily Bourke. Kristen freediving on the Great Barrier Reef.

Kristen piloting an underwater drone.

Image credit: Sophie Rallings. Kristen is holding four elephant trunkfish sea cucumbers.

Kristen with a drone.

Kristen captures photo of research vessel and team.

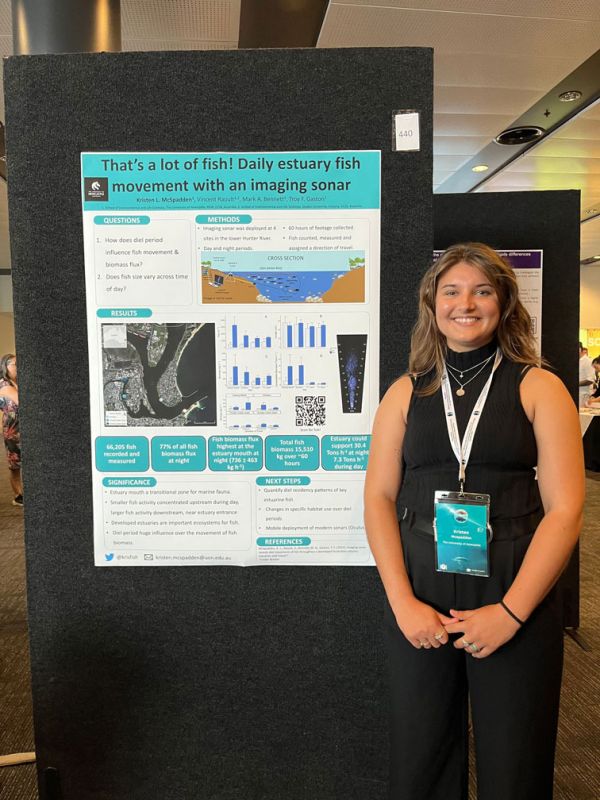

Kristen alongside a scientific poster of her Honours work titled ‘That’s a lot of fish! Daily estuary fish movement with an imaging sonar’ at the ASFB & IPFC conference in Auckland, NZ, 2023.

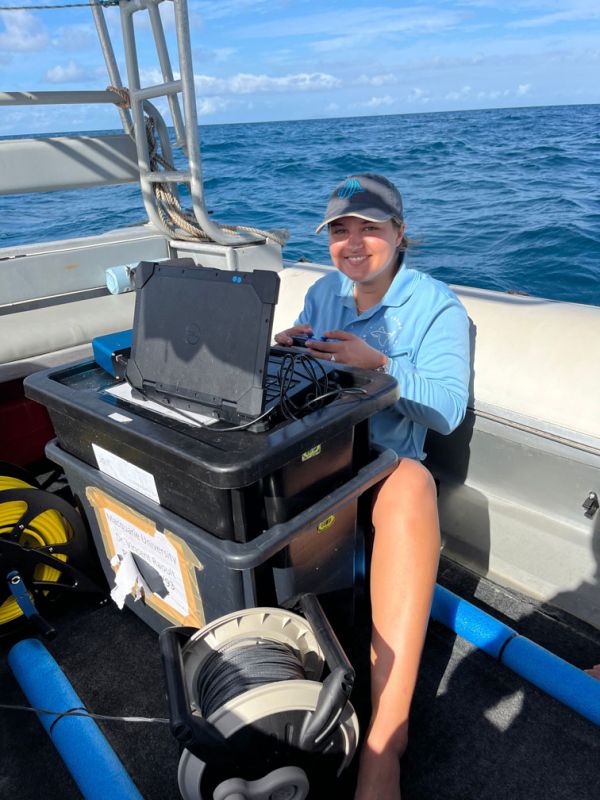

Kristen piloting an underwater drone through a laptop on a boat under a clear sky.

Sea cucumber research team smiling on a boat at sunset, while on a field expedition on the Great Barrier Reef.

Kristen captures image of a white tip reef shark swimming over a sea cucumber, with a researcher snorkelling above the reef.

Kristen holding a sea cucumber.

Kristen holding a large prickly redfish sea cucumber.

Image credit: Harold Bowen

Kristen captures a photo of a large prickly redfish sea cucumber, Thelenota ananas.

Underwater view of a vibrant coral reef, with a curryfish sea cucumber, Stichopus herrmanni, on the sand flat.

A large component of my PhD research examines the trends and sustainability of Queensland Sea Cucumber Fishery, on the Great Barrier Reef. Engaging with the fishery, building relationships and learning from the fishers has been fundamental in understanding the dynamic nature of this industry. Fishers hold invaluable knowledge, and when fishers and scientists collaborate, researchers are better able to inform models, reduce data deficiencies, and improve the overall long-term sustainability of a fishery.

An unexpected branch of my research career has been piloting and servicing underwater robotics. Alongside our research team, I have spent many weeks at sea over the last three years, where I have used underwater drones, known as Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs), to rapidly survey vast areas of the marine benthos. This method allows us to gain high-resolution species level data for sea cucumber populations. These data have numerous applications but broadly support scientists and fishery managers to improve the sustainable management of sea cucumber fisheries.

In my short career as a marine ecologist and fisheries scientist, I’ve had the opportunity to travel to Spain, Indonesia, New Zealand, the Torres Strait and the Great Barrier Reef — researching some of the most exquisite habitats and learning from incredible researchers. It has been an honour to visit some of the most remote coral reefs in Australia and to document the extraordinary species found there.

I carry a growing awareness that climate change may outpace our understanding of many marine ecosystems, altering them before we’ve had the chance or resources to fully document their value. Understanding what we stand to lose in the face of climate change is essential to developing and implementing appropriate marine protections.

I hope to see science continue to grow as an accessible and inclusive space. Informed people are change-makers, and the power of community is a driving force in the movement for environmental protection.

Inspired by Kristen's story?

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.