Researcher Highlights

Spot the difference

Professor Brett Nixon

An investigator of indomitable spirit, Professor Brett Nixon is pursuing the mysteries of sperm dysfunction from multiple, linked perspectives.

What do adult humans, wild rabbits, platypus and Australian saltwater crocodiles have in common? Plenty, according to Professor Brett Nixon. The esteemed educator and innovator studies all four seemingly disparate populations in his research, shedding light on the surprising connections between male factor infertility, contraception and the conservation of endangered animals.

"It's almost paradoxical," he remarks.

"If we can understand the cellular defects present in the sperm of infertile males, then we may be able to develop methods to replicate them in pest animal species to create a new form of contraceptive."

"Physiological insights provided by studying these cells can help us augment the success of captive breeding too."

Though there are "countless things" that can go wrong during the process of fertilisation, Brett is opting to focus mainly on its beginning. Comparing and contrasting samples of sperm that are able to bind to eggs with samples of sperm that can't, the proteomics expert is working to get a grasp on the structure, function and interactions of proteins that differ between the two.

"I specifically look for the proteins that are missing or appear to be behaving abnormally," he explains.

"They may hold a key role in helping to define the underlying cause of male infertility."

Spanning the life sciences and medicine fields, Brett's efforts are also concentrated on improving artificial reproductive technologies (ARTs).

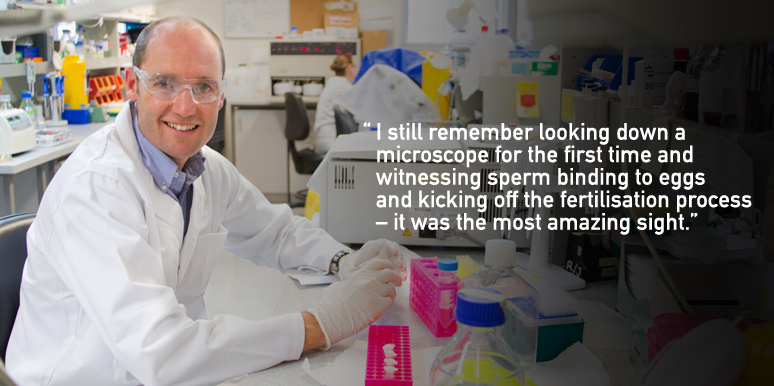

"This long term interest stems from early childhood experiences in which my family were using ARTs to improve the quality of our herd of beef and dairy cattle," the Gloucester native recalls.

"The basic idea was that we would collect eggs from the good mothers and put them together with the semen from the best bulls from around the world."

"The embryos generated were subsequently transplanted into surrogates."

"I still remember looking down a microscope for the first time and witnessing sperm binding to eggs and kicking off the fertilisation process – it was the most amazing sight."

The ties that bind

Brett's career began in 1995, when he undertook a PhD at the University of Newcastle. Completed in Canberra at the Invasive Animal CRC, the ambitious four-year probe centred on figuring out ways to sterilise foxes, rabbits and mice.

"I identified a handful of core proteins involved in a sperm's recognition of an egg and tried to raise an immune response against them to prevent fertilisation from happening," he elaborates.

"This approach was essentially trying to recapitulate a phenomenon seen in a subset of male infertility patients whereby their immune system attacks their sperm and prevents them from binding to eggs."

Seeking to continue his research on male factor infertility, Brett spent the next two years at Emory University in the United States.

"By the time I arrived, scholars within its Department of Cell Biology had developed a mouse model in which they had knocked out one of the key proteins believed to be involved in sperm-egg recognition," he states.

"So in theory, as the mouse can no longer produce that protein, its sperm shouldn't be able to recognise the egg."

"Yet it turns out they were still fully fertile."

Disheartened but not defeated, Brett and his colleagues looked to unravel this improbable twist.

"We started to dissect how a critical element could be eliminated and the sperm still retain its ability to initiate fertilisation," he comments.

"What we have since learnt is that there is likely a lot of redundancy in that initial interaction, so if one protein is removed from the equation, others are available to stand up and take its place."

"There must be a handful that participate, a reflection of the overall importance of this event in the initiation of a new life."

Mechanics and Mother Nature

Brett returned to Australia in 2001, signing on to work alongside Laureate Professor John Aitken at the University of Newcastle. "Too good and exciting an opportunity" to pass up, the past 14 years have been some of the Australian Research Council Future Fellow's most memorable – and productive.

"My team recently conducted a global analysis of the proteins present in fertile and infertile patients," he shares.

"Collaborating with Dr Mark Baker, I came up with a small number of proteins that change consistently between the two."

"At the moment I'm focusing on just one, however."

"We think it's the master regulator that primes the cell for its interactions with the egg."

Faithful to his pastoral origins, Brett has also put in a grant to build up research on sperm-egg recognition in other species. Currently in the process of collecting pilot data for the project, the multitasking academic is specifically interested in applying ARTs to improve the quality of saltwater crocodiles bred at Rockhampton's Koorana Crocodile Farm.

"There is an inherent danger in putting a male crocodile with a female."

"They may fight, resulting in the loss of one or both animals."

"It would be a real advance for the industry if we could just house the latter as is now standard practice in other livestock industries."

Additionally concerned about conservation, Brett is also teaming up with Taronga Zoo on this project.

"We might be able to contribute to improving the success of captive breeding of crocodilian species, many of which are currently threatened or endangered," he suggests.

Asking the big questions

Brett is simultaneously endeavouring to understand why mammals have developed such a "complicated" fertilisation process. Fascinated from an "evolutionary point of view," he's particularly intrigued by the similarities and differences in sperm maturation events that happen in species such as platypus and echidnas versus that of higher mammals and other vertebrates.

"In our own species, sperm maturation takes place over several weeks!" he declares.

"The cells that leave the testes are functionally immature and do not gain the ability to engage in fertilisation until they travel through the male and female reproductive tracts."

"We don't yet know why this is and it is particularly curious given that in species such as the birds, sperm come out of the testes ready to go."

Always willing to lend a helping hand, Brett is not short of praise when it comes to talking about his predecessors and successors either.

"Laureate Professor John Aitken, Conjoint Professor Russell Jones and Professor Eileen McLaughlin have been inspiring mentors," he muses,

"They've pointed me in the right direction when things were wavering."

"I also count myself very fortunate to work with a wonderful group of students, research assistants, and academics."

"One of the most rewarding aspects of my job is the interaction I have with these individuals and watching my students develop research careers of their own."

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.