Researcher Highlights

A good egg

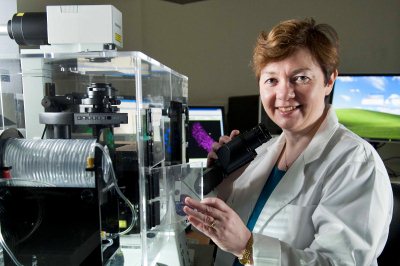

Professor Eileen McLaughlin

The mysteries of conception are this researcher's passion. As a young biologist, Professor Eileen McLaughlin produced her first test tube baby in 1983, just five years after Louise Brown was heralded as the world's first IVF birth.

It was a case of 'right time, right place' for McLaughlin, who graduated from the University of Glasgow to research positions involving assisted reproduction at the universities of Birmingham and Bristol at a time when Britain was the international hot spot in this emerging field.

That experience was the foundation for what has become a distinguished research career in reproductive science. McLaughlin's work has been recognised with awards from the British Fertility Society and the Society for Reproductive Biology in Australia and has been published in esteemed medical journals including Cell and The Lancet.

Since joining the University's reproductive science group in 2001, a focus of McLaughlin's research has been the fertility prospects of older women.

She says her research has reinforced the theory that declining egg quality, rather than quantity, is the major hindrance to conception in women in their late 30s and older.

While science has not delivered a magic formula to improve the quality of mature eggs, McLaughlin is researching the way oocytes, or immature egg cells, are 'woken' to be released from the ovary. The aim is that better understanding this process could lead to new ways of harvesting or prolonging the life of good eggs.

"The attrition rate of eggs is very high," she says. "A female has about 1 million eggs at birth but by the time she is in her mid 30s she is down to about 20,000. By the age of 40, she will have a few thousand," she says.

"She will only ovulate 400 eggs in her life, so the vast majority of them are wasted. The challenge is to find a way to a hold on to some of those good eggs longer."

McLaughlin's work has established that many chemicals used in everyday items such as glues, dyes and pesticides, are potentially toxic to eggs, which can further frustrate the efforts of older mothers to conceive.

"There are increasing numbers of women in their 30s who are having difficulty producing a sufficient number of good eggs to conceive. The evidence suggests that this may be influenced by lifetime exposure, probably at very low levels, to environmental toxicants," she says.

Exposure to these chemicals is a consequence of living in the modern world and McLaughlin says little can be done to reduce women's susceptibility. But the research underpins the importance of her work in trying to extend the life of healthy oocytes and improve outcomes for couples trying to conceive later in life.

Professor Eileen McLaughlin researches in collaboration with the Hunter Medical Research Institute's (HMRI) Pregnancy and Reproduction Program. HMRI is a partnership between the University, Hunter New England Local Health District and the community.

Visit the Centre for Reproductive Science website

Visit the HMRI website

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.