Researcher Highlights

Supporting Research Excellence in the Hunter

Professor John Attia

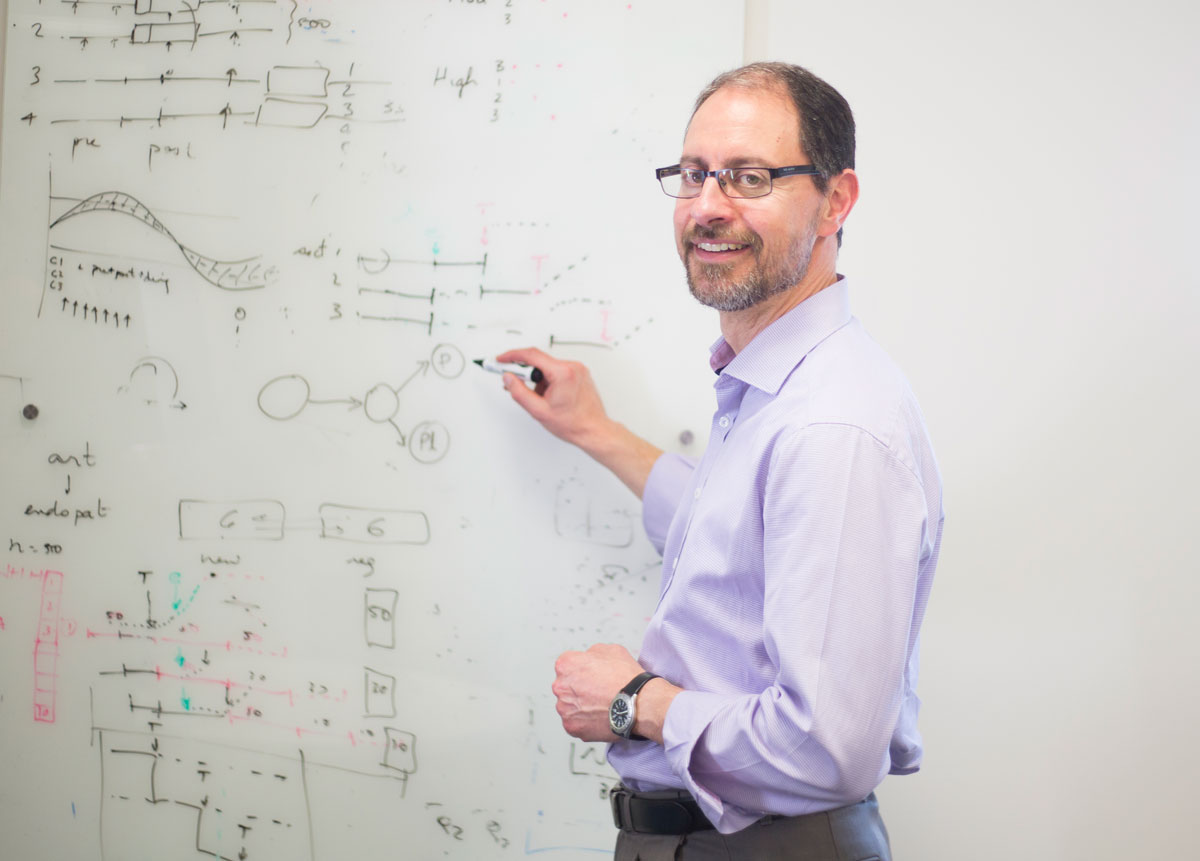

Although he’s not quite where he imagined he’d be, Professor John Attia admits that there’s never a boring day as Director of the Clinical Research Design, IT and Statistical Support (CReDITSS) Unit.

“When I first came across epidemiology, I thought it was probably just going to help me with my own research.

“A major turning point was when I realised I really enjoyed the methods part of it. It’s a really creative process.

“When we sit down with a researcher, we’ll listen to what their question is, what their budget is, what data they have – and we have to think about what's the best way to answer this question within the confines of what is feasible.”

It's not exactly brain surgery ...

As well as working alongside researchers in a consultation capacity, John is not only a researcher himself, he is also a medical doctor. He works at the John Hunter Hospital for three months out of the year as a general physician.

“I always wanted to be a doctor when I was growing up - I really wanted to become a brain surgeon, and I wanted to run a lab too."

“So I went into medical school at the University of Toronto, where they had a joint MD/ PhD program."

“For my first two years at medical school, we studied all the basic sciences, and then I went off and did my PhD in neurobiology."

“After that I did my clinical study years and then went on and did clinical internship."

“Then when I finally got the chance to do a rotation in neurosurgery - I hated it.”

The research environment had also failed to win John over – or so he thought.

John’s PhD project had been entirely lab based, wherein he spent his time searching for an elusive protein thought to be involved with Multiple Sclerosis. Despite trialing a number of scientific methods in his search for the protein, John’s search was fruitless.

“I was working for five years, got nowhere, found nothing and I thought - I'm never going back to research again.”

Evidence-based medicine

Little did John know, there were big changes on the horizon of traditional clinical practice, and those changes incorporated the very field he thought he was finished with.

“Just at the time I was graduating medical school, the whole field in genetic epidemiology was opening up.

“When I did my internship and residency at McMaster University, where the evidence based medicine movement began, I found that I really enjoyed epidemiology and that whole way of approaching and interpreting evidence.

“In hindsight, I recognise now how things work out – the fact that I couldn’t find that protein I was looking for in my PhD, forced me to try all of these different methods.

“That exposure to molecular biology was just what I needed to be able to understand genetic epidemiology.”

“So I brought my basic science and my MD together.”

Around that time, UON was looking to establish epidemiology courses with an emphasis on molecular epidemiology. They had sent out recruitment emails for a Senior Lectureship position via McMaster.

“I applied for that and I got it and things couldn’t have worked out better.”

Vaccination and atherosclerosis

“In 2003, I read a paper in Nature Medicine that really piqued my interest.

“It was looking at the pneumococcal vaccine in mice and how it protected them against the mouse equivalent of atherosclerosis.”

“I looked at it and thought – this is amazing!”

The researchers had found that the “bad cholesterol” which characterises atherosclerosis has molecular similarities to a lipid in the cell wall of the pneumococcal bacteria.

In response to the vaccine, the immune system produces specific antibodies which recognise not only the bacteria but also the fatty deposits in the arteries. Both are marked for degradation by immune cells. Theoretically therefore, the body is protected from infection, and the risk for heart attacks and strokes is reduced at the same time.

“But I looked in the literature and there was nothing on humans.”

Atherosclerosis occurs when fat builds up on the interior walls of blood vessels, causing their diameter to decrease. This increases the risk of heart attack and stroke.

Since this initial publication in Nature, there have been a number of observational studies which find this same connection between the vaccine and heart attack and stroke risk in the human population. But, as any epidemiologist will tell you, correlation does not equal causation.

“I decided that every two years I would put in a grant to the NHMRC, trying to get the money to look at this in the context of a randomised control trial.

“It’s the only way to answer our question– it could be that people heavily invested in their own well-being would want the vaccine and therefore experience these effects, and this would bias the results.”

In 2013, after ten years of trying, John finally got the research grant he had been hoping for.

“We’re now working on a full scale randomised control trial with 6000 patients across five Australian states and territories.

“If we can prove this benefit is real, then one vaccine will work as well as a lifetime of statins or beta blockers - it's the same magnitude of effect in terms of protection.

“Those things cost thousands of dollars plus trying to remember to take your pill every day."

"This is the biggest thing I’ve ever worked on in my career."

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.