Researcher Highlights

From neurons to networks to behaviour

Associate Professor Chris Dayas

A contemporary contributor to understandings of the central nervous system, Associate Professor Chris Dayas is proving – and, at times, disproving – ideas about the brain’s structure and its influence on motivation and emotion.

Mapping the brain is akin to playing Connect the Dots – without the helpful alphabetical and numerical hints. Indeed, in the neuroscience version, the large and obvious points are replaced by much smaller, microscopic cellular arrangements numbered in the billions, and the lines, though similarly serving to join each salient feature, represent the technical and nuanced instead of the sublimely superficial. It’s an almost incomprehensible maze of pathways telling us how and what and why and when we think and act, as intricate and delicate as the organ itself. Associate Professor Chris Dayas, an expert in this interdisciplinary field, is meeting this challenge head-on.

“My research focuses on the brain’s motivation and emotion centres,” he elaborates.

“While they are separate regions, they are highly interconnected and talk to each other.”

I’m interested in exploring these connections, right down to the molecular and cellular changes that occur.

Originally planning to pursue a childhood interest in marine biology, Chris credits several “inspiring” mentors for his rewarding and fruitful switch to neuroscience. Singling out high school teacher and marine biologist Ted Brambleby and university Professors Trevor Day and Janet Keast, the avid surfer and ocean enthusiast speaks of successful crossovers into psychiatry and public health as well.

“I’m passionate about finding better outcomes for pathologies of motivation and emotion, such as drug addiction and depression,” he asserts.

Before we can do this we need to gain a better understanding of the neuroanatomical and neurochemical interactions between key components of brain circuitry that are thought to be responsible for provoking relapse to these conditions.”

“Although much progress has been made in identifying individual brain regions that elicit reward-seeking behaviour, there are presently very few effective therapies available to treat pathological reward seeking – a core symptom of addiction and obesity – as well as depression, where the opposite occurs, you see low motivation and reward seeking.”

Getting specific

Chris’ research career began in 1997 when he undertook a PhD at the University of Queensland. Chiefly concentrating on the emotional side of the brain, the four-year probe sought to investigate how the brain responds to different types of stress.

“At the time, there was general consensus among scholars that the brain responds to all types of stress the same way,” he recalls.

“I identified, however, that psychological stresses, or ‘perceived threats’ important for the onset of neuropsychiatric conditions such as depression, activated a different part of the amygdala compared to physiological stresses, such as hypoxia and haemorrhage.”

“I found that psychological and physiological stress elicits distinct activity ‘footprints’ within this subcortical structure as well as sub-populations of catecholamine cells, like noradrenaline and dopamine cells within the brainstem.”

A stubborn problem

Awarded a prestigious CJ Martin Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) after receiving his award in 2001, Chris relocated to the United States to undertake postdoctoral training at The Scripps Research Institute. Principally focusing on alcohol addiction, the 2002-2006 stint in California’s sunny and surf capital ended up “intellectually fusing” two of the Brisbane native’s primary interests.

“The parts of the brain that deal with stress connect to the hypothalamus, which reacts to drug abuse,” he explains.

“I endeavoured to bring these two interests together.”

Aspiring to help build a solid knowledge base around the neural pathways that control reinstatement of alcohol relapse, Chris published his overseas findings in the high profile journals Biological Psychiatry and the Journal of Neuroscience.

“We showed that cells in the hypothalamus, which people used to think were important solely in food-seeking, are involved in drug addiction too,” he reveals.

“Hypothalamic peptide systems, better known for their role in feeding behaviour, may therefore be significant neurotransmitters in the brain circuitry that trigger alcohol-seeking behaviour.”

“We’re still studying them very closely.”

Creative and scientific in equal measure, Chris employed a number of different methods to shed light on these connections.

“We used antibodies to bind to the cells and immunofluorescence to look at their structure,” he shares.

“Markers of activity were also established to help analyse how the cells changed over time.”

“I was lucky enough to work with Associate Professor Brett Graham, an electrophysiologist, and Dr Doug Smith, a molecular biologist, as well.”

Pinpoint accuracy

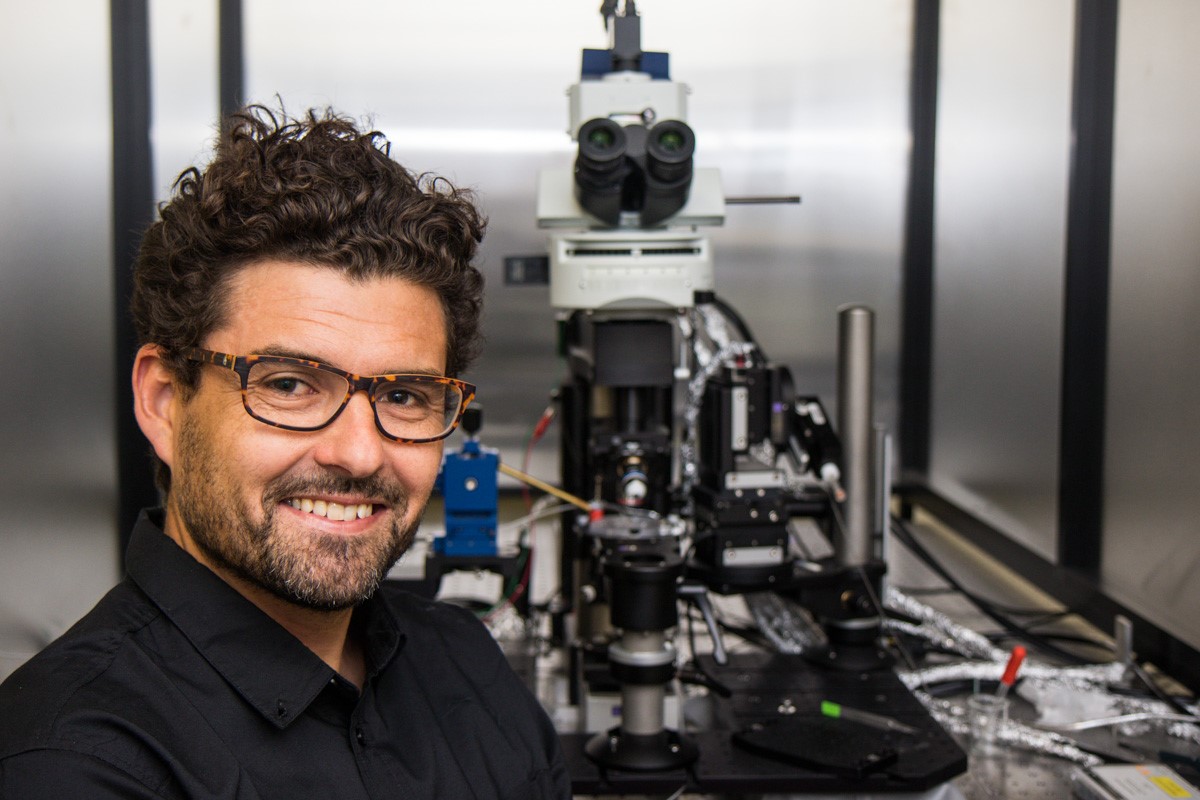

Chris moved to the University of Newcastle in 2007 to set up his own laboratory in the Discipline of Anatomy, School of Biomedical Sciences and Pharmacy where he continues to examine the role of hypothalamic peptides in driving drug-seeking and relapse-like behaviour.

“I received a generous grant from the NHMRC to commence this work,” he states.

“We’re applying new, cutting-edge techniques to see how cellular connections alter following drug abuse or chronic stress.”

Referring particularly to optogenetics, which involves the use of light to control cells in living tissue, Chris believes these new “genetic tricks” will quickly advance our understanding of the brain, and hopefully identify new treatments.

“My group is using this process of inserting light-activatable proteins from algae into various types of brain cells,” he discloses.

“This will allow us to experimentally ‘shine a light’ on connections between different parts of the brain.”

“Glencore recently awarded us a philanthropic grant to buy a specialised ‘optogenetics’ microscope specifically designed for such a purpose.”

“It’s in its early days but we’re getting some fascinating results.”

Related links

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.