Researcher Highlights

Honing in on her target

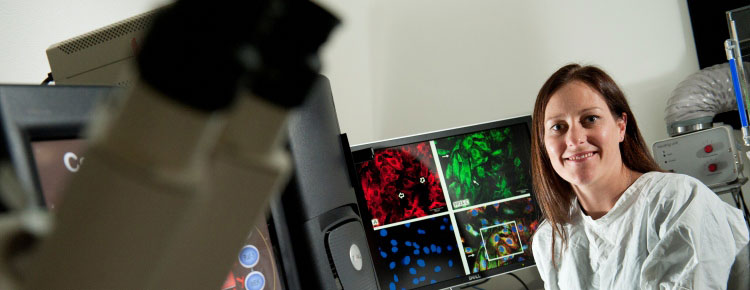

Dr Nikki Verrills

Dr Nikki Verrills' research into a key signalling switch in cancer cells could provide an important breakthrough in treatment.

As a young undergraduate studying science, Dr Nikki Verrills had intentions of transferring to medicine. Then, she discovered a passion for laboratory research and realised she could effectively fight disease on another front.

"In the end I have achieved the best of both worlds," the biochemist and cancer researcher points out. "I am still in the medical field helping patients by contributing to the development of better treatments but I am also able to pursue my interest in lab work, which I find fascinating."

Verrills has certainly found her niche. Since completing her PhD in 2005 she has worked largely full-time in academic research, collecting a clutch of early career awards, fellowships and major grants in recognition of her groundbreaking research into leukaemia and breast cancer. She studies the molecular pathways of cancer, identifying genes and proteins in cancer cells in order to make comparisons between normal cells and cancer cells. She also analyses differences between cancer cells that respond well to drug treatments and those that do not.

"If scientists can identify proteins that are different in cancerous cells, or in drug-resistant cells, then we can design drugs to target those differences – drugs that will specifically kill cancerous cells but not normal cells," she explains. "That is fundamental cancer research, but most cancer drugs work by turning off a particular protein, or inactivating it. What is novel about our work is that we have targeted a protein that needs to be switched back on."

That protein is phosphatase 2A, or PP2A, which comes from a class of proteins known as 'tumour suppressors'. Normally, they act as a stop signal to inhibit the growth of cancerous cells. In leukaemia cells, however, PP2A is inactive, so the cancer cells continue to proliferate.

In 2007, Verrills worked with collaborators in the United States to prove that the drug FTY720 could effectively switch PP2A on in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) – therefore stopping the cancer's spread without affecting the body's healthy cells. This year she was awarded a $360,000 grant from the Cure Cancer Australia Foundation and Cancer Council NSW to apply that research to a different cancer, acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), which has a very poor survival rate.

"There is a real urgency to find new treatments for AML because the vast majority of patients are resistant to chemotherapy and will die of the disease," Verrills asserts. The grant will allow Verrills and her team to test FTY720 and other drugs in different sub-types of AML, and move their work from the laboratory into clinical trials.

"Another focus of our work is establishing exactly how these types of drugs work," she outlines. "We know the end result is that they increase activity of PP2A but we want to advance the knowledge in this field by finding out specifically how they do that. Also, we know from literature that this class of proteins is important in a lot of solid tumours, so it is likely that this research will be applicable to other cancers as well."

Verrills has received ongoing support from high-profile national cancer organisations and has forged collaborations with key research groups in Australia and internationally. She also works closely with colleagues in the University's Centres for Cancer and Chemical Biology and through her links with the Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI) has established important working relationships with cancer specialists and haematologists. Her articles are published in internationally prominent journals and she has been recognised with a Voiceless Eureka Prize for Research for her commitment to minimising the use of animals in laboratory work.

Verrills' doctoral studies into chemotherapy resistance in childhood leukaemia led to a Peter Doherty Postdoctoral Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council in 2006. In the same year she was the inaugural recipient of a Hunter Medical Research Foundation grant for young cancer researchers. She is currently supported by an Early Career Researcher Fellowship with the Cancer Institute of NSW.

Verrills gained exposure during her doctoral studies to cutting-edge scientific techniques used at the Australian Proteomic Analysis Facility, in Sydney, becoming one of the first researchers in the country to use Difference In-Gel Electrophoresis (DIGE). This technique allows simultaneous analysis of proteins in cancerous, non-cancerous and control cells and vastly improves the efficiency and accuracy of testing.

The scientist admits that work/life balance is an elusive concept given her demanding research career, two young daughters and family interest in a vineyard (in which her husband Michael De Iuliis, a fellow scientist, is chief winemaker). But she praises the support of the University of Newcastle, which has allowed her to maintain the momentum of her research while juggling life's other commitments.

"Not only has the University supported me but it has also shown a lot of confidence in me, which is critical for career advancement," Verrills acknowledges. "I have my own research group and I have reached the stage of being an independent researcher much earlier than I probably would have anywhere else."

Visit the Priority Research Centre for Cancer

Visit the Priority Research Centre for Drug Development

Visit the HMRI website

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.