Researcher Highlights

Translating research into practice and policy

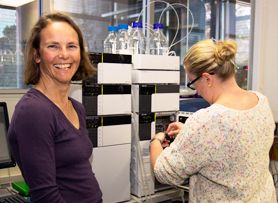

Professor Jennifer Martin

Optimising choice, dose and timing of medicines for a particular patient are the focus of Professor Jennifer Martin's clinical work and research career.

Professor Jennifer Martin is the Chair of the discipline of Clinical Pharmacology in the School of Medicine and Public Health at the University of Newcastle.

Working in the Hunter New England Local Health District, Jennifer leads a team of pharmacy and medicine experts together with pharmacoepidemiologists and pharmacoeconomists, who work across a number of areas including cancer.

Most often centering on therapeutic drugs, the team look at everything from the design and development of drugs, to the clinical trials process, through to the post-marketing phase, where data is collected on how effective those drugs are in practice, and any side effects they might have.

MEDICAL CANNABIS TRIALS

In July 2015, the NSW government announced Australia's first medical cannabis trial for terminally ill adult cancer patients. The Hunter will serve as a recruitment hub for this study and the UON clinical pharmacology group will lead the dose-finding study in the Hunter, together with UON's Conjoint Professors Stephen Ackland and Katherine Clark.

Although likely to polarise opinion, the study could significantly improve the well being of terminal patients at the end of life.

To be conducted in two phases, the trial will assess the ability of cannabis to relieve symptoms including fatigue, low appetite, altered taste and smell for food, low mood, weight loss, nausea, insomnia and pain relief.

Jennifer believes the team was chosen to run the pharmacology aspects of the cannabis trial due to the long history of excellence in the UON Clinical Pharmacology department (previous Chairs include Emeritus Professor Tony Smith and Professor David Henry), and the high level of analytical support offered by the University of Newcastle, led by Dr Peter Galettis.

In line with her focus on optimising the therapeutic benefits of medication, Jennifer sees this trial as a vital opportunity to assess and quantify a drug already being used by many extremely ill patients.

The first phase of the trial will produce world-class pharmacokinetic analysis and sophisticated modelling to inform drug dosage and frequency of administration.

CHALLENGING CONFOUNDERS

Jennifer dismisses the notion expressed by certain quarters of the community that this trial has more to do with political agenda than patient quality of life.

"At the end of the day, we want our patients to access this drug if it proves effective."

"Identifying exactly what helps, how it helps, how much a patient needs and possible side effects is vital," she says, "especially if those side effects are worse than the symptoms being treated."

The team is sourcing pharmaceutical grade cannabis from commercial suppliers overseas who complete rigorous testing, which rule out contaminants such as mould, and authenticate uniform potency.

To further ensure consistency throughout the trial, vaporisers have been chosen as a method of delivery.

"We know that when you eat cannabis in food, there is a huge variability between the amount that you eat and how much you actually need to feel good," Jennifer explains.

"This depends on what meal you have eaten, other drugs you have taken and how well you are."

"But if you inhale it, it goes straight through the lining of your nose or mouth into the bloodstream," she continues.

"If we can be sure the equipment and potency of the cannabis are uniform, we don't have any confounders muddying our understanding of the relationship between dose and effect in a particular person."

THE ROAD TO RHODES

Jennifer spent her childhood in Wellington, New Zealand, where her initial interest in medicine grew from a love of sport. She decided early on that she would become the doctor who travelled with the New Zealand Olympic team.

While studying at the University of Otago, changes to tertiary funding forced medical students to take out large loans, with interest accruing during their student years. Upon graduating, many began work as doctors in New Zealand, but then moved to the United Kingdom or Australia, to pay off their increasing debt.

"By that stage, my eyes were opened to the issues of unequal access to tertiary education, health care and user pays," she recalls.

In 1993, keen to further understand the consequences of inequity in healthcare access, Jennifer was awarded a prestigious Rhodes Scholarship to study politics, philosophy, and economics at the University of Oxford.

Returning to New Zealand, Jennifer trained as a specialist in pharmacology and internal medicine.

"I like that pharmacology is the study of drugs across all areas."

"You get very broad training, but it is also closely related to those wider issues of access to health care resources and drugs," explains Jennifer.

In 2000, Jennifer went to Melbourne to undertake her PhD from Monash University, examining innate immunity in Type 2 diabetes. Subsequent postdoctoral work at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute focused on the function of macrophages with high fat diet. A stint at the University of Queensland as Head of the Southside Clinical School followed. Here, Jennifer became involved in medical curricula as a method of broadening the experiences and understanding doctors have about medicine and healthcare.

The opportunity to apply for the Chair of Clinical Pharmacology at the University of Newcastle combined with encouragement from leaders in the field to do so, convinced Jennifer to pursue the clinical pharmacology leadership position in 2013.

TEAM COACH

Jennifer is quick to point out that the entire Pharmacology team is working toward the improvement of patients' lives, not just on the cannabis trial, but on a range of research and community leadership roles in medicines' use.

She sees herself not as someone who must actively manage the work of those she leads, but more of a coach helping her team to reach their goals.

"We have a general understanding that people in this group contribute to clinical and medicines research and service."

"They are in charge of pursuing their own research agenda but we need to provide support and opportunities for that," she explains.

Postgraduate students under Jennifer's supervision are developing a mass spectroscopy library and clinical validation for synthetic drugs of abuse, and developing programs to optimise dose and timing of cancer therapies.

Future research will continue to focus on drug individualisation using drug phenotype data, and developing evidence around biosimilars.

Members of Jennifer's team also have a focus on generating evidence to guide the deprescribing of medications - particularly in people with a lot of comorbidity or at the end of life.

MOTIVATED TO RIGHT WRONGS

An intuitive and award winning teacher, Jennifer's style in the classroom is somewhat unconventional.

"My classes are very interactive because I want the students to think," she says.

"We do everything on the whiteboard so they have to interact."

She laughs as she reflects on her propensity to be diverted by tangents in class, but solemnly states her belief that teaching well involves admitting to past errors to prevent students from repeating them.

"I think one of the most important functions of being a professor is mentoring and training the next generation. I think it is a shame that the university system rewards you so well for research but not for teaching."

Not that Jennifer could ever be accused of lagging in research, or any other aspect of her career.

The practicing physician, teacher, researcher, multiple committee and editorial board member, and mother of four wants you to know she is not as intimidating as she looks on paper.

"I am very aware of the impression I make when I say things like 'I was a Rhodes Scholar'," she reflects.

"I just applied for the scholarship, had a vision of what I wanted to do and I got it. So I don't think of it as any badge of achievement, it was just what I did."

"The experience has cemented a responsibility to do something helpful for the community," Jennifer adds.

"I am motivated, but my motivation is to try and ensure equity of access to opportunities based on merit in a society of entitlement, where some people get preferential treatment."

"I know I can't override thousands of years worth of inequity, but I'm doing it in my own small way and I hope that it eventually has some benefit in terms of access to medicines."

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.