Researcher Highlights

Solving real-world problems with microbial discoveries

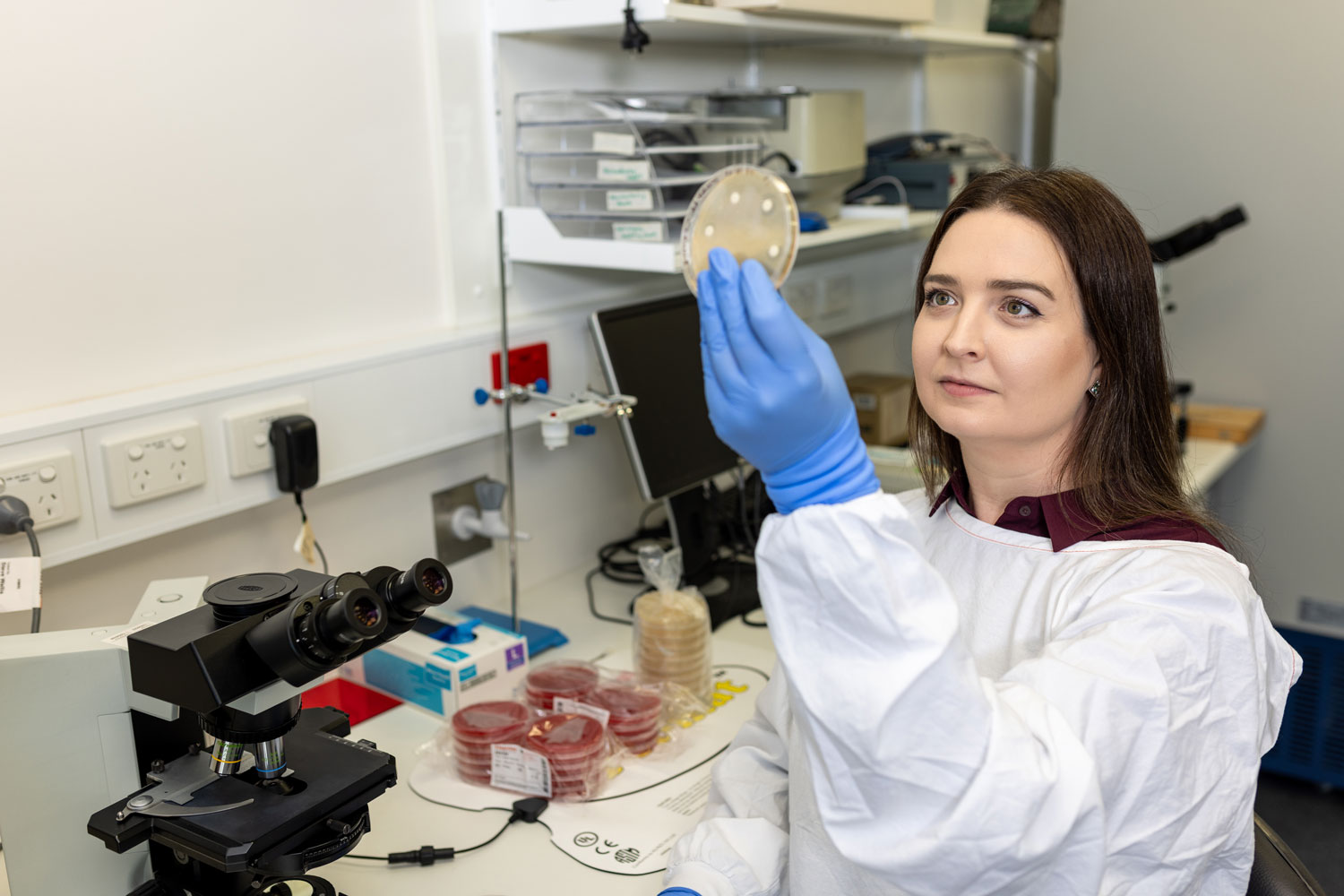

Dr Emily Hoedt

Biotechnology graduate and research fellow Dr Emily Hoedt is making exciting discoveries in the field of microbiology. From optimising soldier cognition to improving surgical outcomes, she's showing what a big difference small things can make.

Emily is a trained microbiologist examining microbial communities with computer-based analyses (metagenomics) to study the diversity, roles, and responses of microbes in different environments, focusing on how they function and adapt under various environmental conditions.

She currently works at the University of Newcastle as a member of the Centre of Research (CRE) in Digestive Health team, overseeing all aspects of microbiome research.

The present focus of her efforts is on attempting to understand how to manipulate microbiome ecosystems through nutrient and/or community dynamics.

A big fascination with tiny organisms

“I’ve always found microbiology fascinating,” says Emily.

“The fact that there are these tiny microbes working unseen to make a living in the environment around us (even in the harshest conditions) and within our bodies goes underappreciated.

“Our relationship with microbes is complex and still largely unclear. We can only grow 29 per cent of the microbes that live in our gut, so there’s so much to uncover, and this is what drew me into microbiology. Discovering a new microbe, understanding it and even naming it was very exciting.”

An influencer of microbiology

To date, Emily’s microbiology and microbiome research has influenced fundamental microbiological understandings.

Her development of methods to isolate and culture-specific microbes resulted in the recovery of metabolically novel microbes. It also improved the feasibility of shotgun metagenomics from low microbial load samples—making it easier to study the microbes when there aren’t many in a sample.

This is significant as typically small samples have presented challenges for analysing the genetic material (DNA and RNA) of complex microbial communities.

Emily has also contributed to the understanding of the functional capability of the gut microbiota, and the identification of food-microbiome interactions is influencing dietetic practice in digestive health and wellbeing.

Her work involves collecting biopsies and stool samples from the gut to profile the microbes that live there. Using computer-based analyses, she can then target them for growth and recovery and test how they interact with human cells.

One of her contributions in this area includes the identification of key microbes in Crohn’s disease, which has progressed understanding of inflammatory bowel disease.

From infant formulas to soldier cognition

In 2018, Emily relocated to Ireland to undertake work with APC Microbiome—a role that required her to plan, manage and liaise with an industry partner.

The assignment involved the molecular (DNA) interrogation (in silico-computer based) and manipulation (in vitro-testing DNA function in the lab) of bifidobacterial strains. It also included assessing potential host and microbiota (in vivo- lab model) benefits during gastrointestinal distress (antibiotic and/or pathogen) to determine the commercial viability of the bifidobacterial strains as a probiotic product.

This research contributed to the exciting development of a probiotic formulation that may recover infant gut microbiomes after antibiotic treatment. It also expanded her professional network and experience in international science.

Emily has also collaborated widely on several other projects investigating the broad impact the microbiome has in areas such as digestive health diseases and disorders and brain function and performance.

One is a joint $3.5 million project funded by the Department of Defence.

Harnessing the unique relationship between the gut and brain, this research investigates the gun-brain axis in relation to cognitive performance in soldiers.

"The overall hypothesis is that gut microbiome composition and function is associated with cognitive performance and mental fitness/resilience. And that strategies to modulate the microbiome can be developed to optimise cognitive performance under the extreme pressures of operating in contested/complex environment," says Emily.

Improving colorectal surgical outcomes

One of Emily's major focuses currently is the microbes associated with unsuccessful colorectal resections.

Colorectal resection is the mainstay treatment for many diseases that require surgery. This includes colorectal cancer, diverticular disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.

The rejoining (anastomosis) and healing of the remaining tissue is not always successful and can result in sepsis (intestinal contents escaping into the abdomen: anastomotic leak).

This event has devastating consequences for the patient, says Emily.

"Most have salvage surgery, but some don’t survive the infective insult (~16.4 per cent mortality rate). Despite progress in many aspects of surgical care, leak rates remain high, between 10-15 per cent in large series and cohort studies."

There is indisputable evidence of the gastrointestinal microbiota's role in the host's homeostatic function, gastrointestinal disease, and wound healing.

Therefore, Emily's research aims to identify biomarkers from the tissue microbiota at the site of the anastomosis that are associated with anastomotic leak and design an appropriate intervention to target this biomarker and improve colorectal surgical outcomes (anastomotic leaks).

"This will be achieved using metagenomic shotgun sequencing and metatranscriptomics to inform us of the microbiota community composition, functional capability, and specific microbial gene expression," she continues.

She was recently one of two Newcastle scientists to receive a $500,000 NSW Health Early-Mid Career Researcher Grant to fund this work.

Changing the world with her voice

A discovery Emily is most proud of is when she isolated a new type of methane-producing microbe from a kangaroo that no one else had seen before. She was the first to report on a new way to make methane (ethanol and methanol).

Unfortunately, she didn't get to name this bug.

While her work in microbiology is highly valuable in its approach and applications, Emily admits that she finds it hard to feel like she's changing the world from the lab and by publishing academic papers.

Because of this, she's always keen to accept any opportunity to present her research and excitement about the microbiome to the wider community.

In the past, Emily has spoken at events such as Parkinson's community seminars, Men's Probus Club colorectal cancer seminar, HMRI Healthy Ageing community seminar, HMRI donor events, and GP education events.

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.