Researcher Highlights

Turning data into music

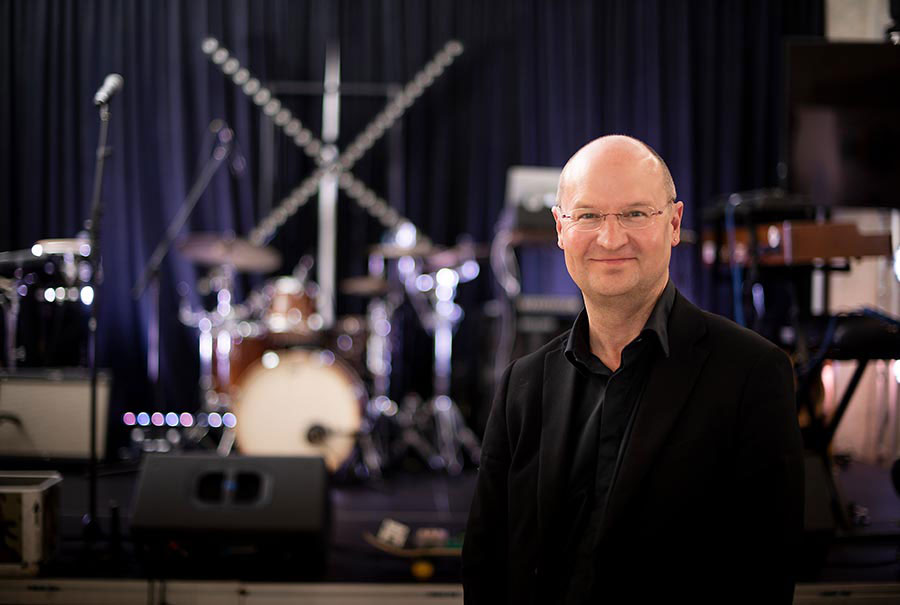

Associate Professor Jon Drummond is transforming art, nature and data into music to highlight scientific discoveries in a way that is accessible and creative.

Associate Professor Jon Drummond’s research, which combines music with computing, is helping less accessible scientific research come to life and reach a wider audience.

Drawing on the skills of sound design, composition and software design, Drummond collaborates with other artists and scientists in the field of sonification and data visualisation. His research looks at the ways that the world of data we live in can be represented in both sound and digitalisation through creative coding.

“I work primarily in the arts/science domain so my work is about how sonification can help tell the story of science,” Drummond said.

The composer and sound artist began his studies at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music as a classically trained musician studying piano performance and composition

when he discovered the potential of working both in the music studio and with computers. He went on to do a Masters of Science in computer engineering to the develop software skills needed to create and manipulate sounds and use software to compose music. His PhD examined interactive electro-acoustics, sonification and visualisation.

Highlighting the demise of the bumble bee

Across Northern Europe the fields are an eye catching green, however the lack of flowers means the landscape is as barren as a desert to the bumble bee.

Drummond was one of the researchers on a large-scale project rolled out across the Netherlands and North Germany, known as ‘Oratorio for a Million Souls’.

Collaborating with thousands of bees, this project created three architectural structures, in the form of traditional bee ‘skeps’ in botanical gardens in Buitenpost (Fryslan) and Oldenburg and Emden (Germany). To generate empathy with the dire state of bees in the face of commercial farming, pesticides and global warming, these three ‘Oratorios’ contained Bumble Bee nests equipped with audio and data sensors that created a multi-channel real time opera audiences could participate in. In a unique inter-species situation visitors could experience the uncanny sensation of being located in the heart of a massive bee city.

“Multiple stories of sustainability and environmental impact could be told through this process. The public could go in and see and hear the visualisation of the data, hear the bees and open up a dialogue with the scientists who have been researching the plight of the bumble bee,” Drummond said.

“One of the best moments of that project was when we installed the skeps in the garden and the general public came through and we could sit back and see the conversations unfold about the environmental situation and hear people talking about how they could make a difference and help save the bees.”

Drummond also turned the data and sounds recorded in the hives into music that brass bands played to local audiences, further enhancing public interest in the project.

“The beehive entry and exits were heard as pulses in the music. The bees would have a slow start to the day then activity increased as the day wore on then slowed down, so that provided a rhythmic framework for the musical piece. We used the frequency of their buzz to provide a scale,” Drummond noted. “The brass band performances of the bee soundscape invited further discussion around the environmental situation.”

Interpreting art as sound

Another of Drummond’s projects brings to life musically the artworks of Arthur Boyd. In a collaboration with scientists, artists, media and communications academics the project tells the history of Arthur Boyd’s Bundanon property which was gifted to the Australian people following his death in 1999.

Scientists conducted a mineral analysis of the soil at the property and discovered when human habitation began in the area and also revealed the story of Arthur Boyd’s use of paint.

“The mineral analysis showed the use of lead and cobalt in the art studio. We analysed the mineral data and produced a unique visualisation in conjunction with a Geiger counter inspired soundscape that played individual notes. Low notes for the heavy elements and high notes for the lighter elements,” Drummond said. “Visitors to the site were invited to use an app on their phones to access the data and soundscape while walking around the property. The app also provided multimedia material on the history of the property.”

Drummond collaborated with artist Nigel Heyler on another project that brought to life Boyd’s artworks. He invented a camera vision system to read the minerals in Boyd’s paintings and interpreted this data as a compelling sound composition. The resulting installation, Heavy Metal, invited visitors to interact with Boyd's paintings in his old studio at the Bundanon homestead to discover a hidden world of elements and minerals in an experience that was simultaneously chemical, visual and musical.

“We used a camera on Arthur Boyd’s paintings to get a colour measurement which we could then correlate to a pigment which we could then correlate to a mineral spectrum. It was a playful installation that allowed you to ‘play’ the painting with music. We were able to access Boyd’s piano and turned the piano sounds into painting sounds,” Drummond explained.

Using sonification to relieve stress

It’s Drummond’s fascination with the way that humans can be both moved and inspired by sound and music that lends itself to his collaboration with Dr David Cornforth, a computing researcher at the University of Newcastle. They are testing the potential of sounds and sonification to relieve stress.

“This project will undertake a study of simple to use, commercially available Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) devices and music, sound design, and environmental soundscapes for a personal health biofeedback system,” Drummond said.

“We’ll be using the BCI device to measure the patient’s brainwaves while also delivering sound to their ears,” he said. “We know anecdotally that music and soundscapes can help with relaxation and reducing stress but we are aiming to measure scientifically what impact the sound has on the patient’s heart rate, respiration, brainwaves, temperature and blood pressure. We’ll also ask the patient to complete a depression and anxiety questionnaire.”

“By measuring their physiological response to sound we can clinically report what effect the music has on a patient’s emotional state.”

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.