Researcher Highlights

From computer science to neuroimaging

Research Assistant Aaron Wong

Dr Aaron Wong was initially spurred into the world of computing science thanks to the foresight of his parents – who enrolled him into coding workshops when he was just seven years old. Today, his interdisciplinary research journey is motivated instead by a love of learning and collaboration.

Although Aaron dabbled in a number of extra-curricular activities throughout his primary years, including attempting to learn Chinese, coding was the one that stuck. Aaron admits that his Chinese language skills may have suffered as a consequence: “My accent is terrible,” he confides

But although the lack of language skills may have disappointed his RoboCup team-mates at the 2008 World Championship in Suzhou, China, the NUbots couldn’t have had too much to complain about when Aaron’s well-refined coding practise helped launched them to global victory.

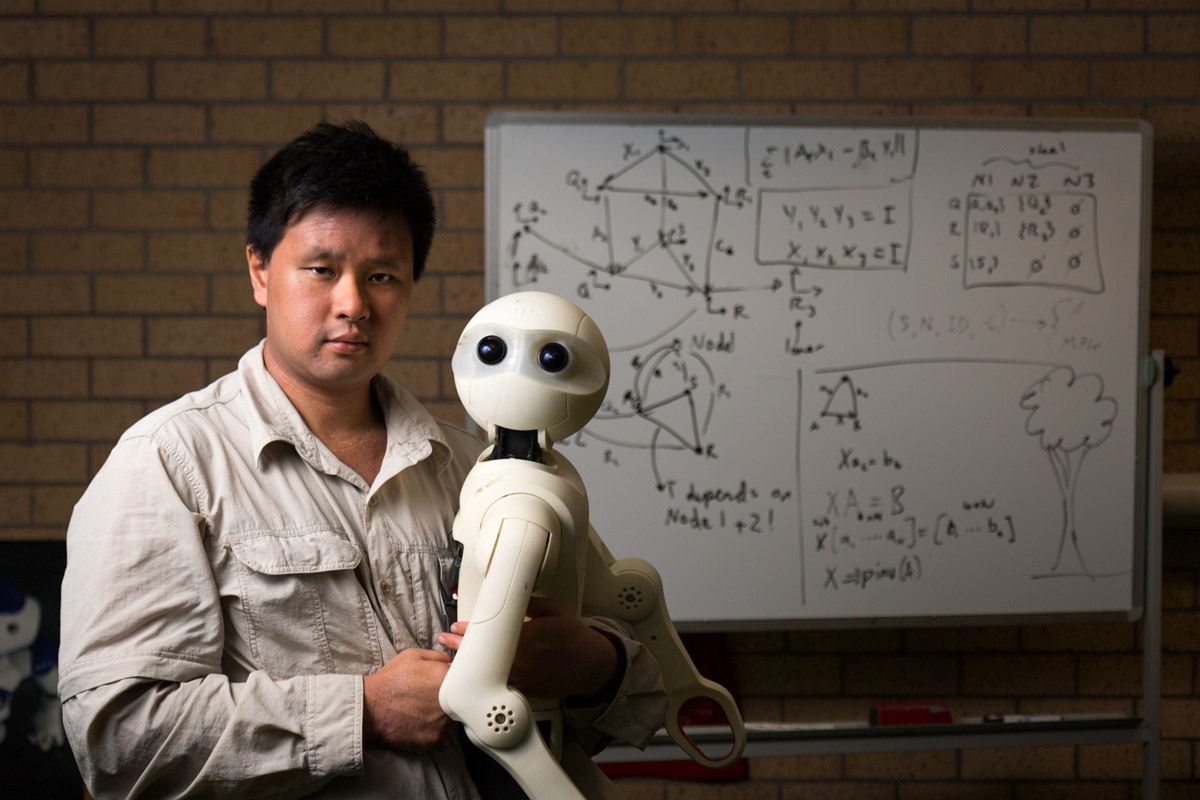

NUbots are autonomous, football-playing robots who compete across the globe in soccer matches. While they seem like just a cute bit of fun, the aim of RoboCup and the footy-playing robots is to combine artificial intelligence and robotics to develop solutions in the broader AI and robotics fields.

Although most students get involved with the NUbots projects within the Newcastle Robotics Laboratory, led by Associate Professor Stephan Chalup, as part of coursework or summer scholarship programs, Aaron was invited onto the team because of his natural programming flair.

He had been enrolled in a double degree in Computer Science and Computer Engineering at UON– a career choice which had been a long time in the making.

“I always knew I wanted to do something in the field of computing - I had a knack for programing because I started really young.

“I was interested in the foundations of mathematics, so coding was just the way that I applied that skill set - I found it easy and I took off with it.”

Once Aaron progressed to high school, he became fascinated instead with computing hardware. He began fixing computers for fun when he was just eleven years old – a hobby which he explains was merely a consequence of the natural progression of his interests.

Of robots and rescues

Throughout his undergraduate studies, Aaron become engrossed in the field of artificial intelligence (AI), and continued in his machine learning research throughout his Honours and PhD projects.

“I started off programming a rescue robot to compete in the RoboCup Federation – it was an autonomously driving wheeled robot designed to find victims in a disaster scenario.

“I concentrated on sound recognition and localisation. Because the robot was so low to the ground, sound was pretty much the only way of finding people.”

From there, Aaron moved on to acoustic and image processing for his PhD. Then, through a roundabout series of research questions and aims, he found himself specialising in the unusual task of teaching of emotions to robots.

“We were combining together all the sensory and effective processing.

“So we’d pull out all the visual features we were interested in - like colour, fractal dimension and facial perception (paredolia) – then feed that into a learning algorithm to get the robot to learn by itself via user feedback.”

When Aaron was offered a part time technical support position within Associate Professor Frini Karayanidis’ Functional Neuroimaging Laboratory, his new working environment saw this emotional learning aspect truly came into focus.

“There was definitely an overlap – and it helped me with my writing too, that I was able to concentrate on the biological and psychological perspective of the project.

“That general integration of sensory input which is basically what our brain does. We don’t know exactly what happens there but we’ve got lots of bits of ideas.

“What I could then do was build those ideas into my engineering project.”

Combining collaboration with innovation

Since finishing his PhD, Aaron has moved on to work with a number of research groups from across the University, including with the team at his old PhD stomping ground, the Functional Neuroimaging Laboratory.

“I’m really open to collaboration – I’m flexible and have found I can work with just about everyone.”

At the moment, Aaron is involved with UON’s PRC for Stroke and Brain Imaging’s streamlining of patient assessment techniques. They are hoping to minimise the need for number of pricey MRI scans performed in the clinic.

“To infer brain function from MRI costs much more and takes a lot longer, when compared with an EEG.”

By building a model which feeds EEG and MRI data together, patterns between the two types of data can be used to predict MRI results from EEG scans.

“The project is a massive data mining process - but it should eventually save clinics a lot of time and money.”

STEM outreach solutions

Aware of the difference an early start can make to a child’s attitudes to science and learning, Aaron is now invested in primary school workshops much like the ones he benefited from as a child.

Aaron initiated UON’s RoboCup Junior project in 2011 when he was approached by a parent at a RoboCup event.

“He was really keen to start something like what we were doing but for younger kids.

“It’s good for them to be able to see the practical applications of engineering from an early age, and to realise it’s all about having a go.”

“It’s that iterative learning process - writing one line of code and sending it out to the robot. Then asking – ‘Does it move, does it not? Did I do something wrong, did I do something right?’

“You can assess that step by step, and that's the kind of logical thinking that you need to be an engineer. You need that ability to break down your jobs into tiny little steps so you can go ‘Tick, tick, tick!’ - also it builds your confidence as well.”

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.