Researcher Highlights

The politics of history

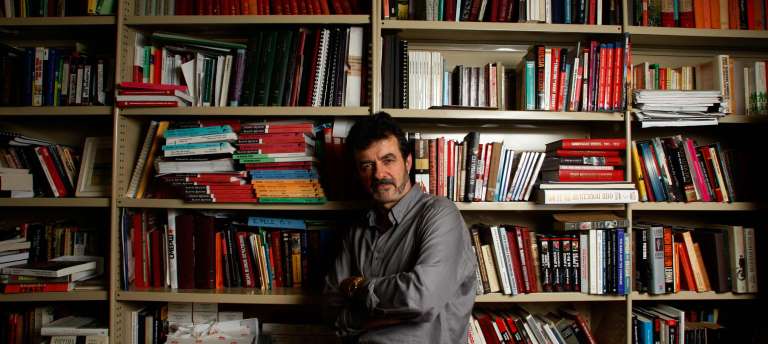

Professor Roger Markwick

Roger Markwick, Professor of Modern European History and founding member of the Centre for the History of Violence believes the way we frame our past is pivotal for our understanding of the present.

George Orwell's famous quote: "He who controls the past controls the future. He who controls the present controls the past (1984)," holds particular resonance for European historian Professor Roger Markwick, whose analysis of the role of Soviet historians and historical writing in the twentieth century has important implications for current times.

As a specialist in modern Russian and Soviet history and historiography, with other interests in European fascism, genocide, and colonial settler states, a central theme of Markwick's research is how historical discourse can influence not just the way a society views itself, but its very survival.

In studying the driving forces behind the October 1917 revolution that gave birth to Soviet society, and its subsequent demise, Markwick investigated how historiography in the Soviet Union became politicised to the extent that the party-controlled version of events became intrinsic to the longevity of the Stalin regime.

The crudest mechanisms of censorship during the Stalin era included the closure of archives, banning of original research, forced adherence to historical texts which celebrated Stalin, and the terrorising, jailing and execution of historians who did not agree with the received historical wisdom.

Under Gorbachev's perestroika, the history and the mythology that had grown up around it were challenged, playing an important part in the unravelling of the Soviet Union.

"For the first time historians began to act as independent scholars, dismantling the mythology around Stalin and, by association, Lenin – thus weakening the ideology of the system itself," Markwick said.

"What fascinates me is the degree to which history and historians can play a part in either legitimating the status quo or de-legitimating it. History was politically pivotal in the old Soviet system. It remains so today in post-Soviet Russia, particularly the traumatic history of the Second World War Eastern Front, which has now become a research focus for me.

"But much the same can be said for the way history frames national identity in other countries with a violent history, such as Germany, Italy and even Australia. Here, the Anzac legend has achieved almost sacred status and those who challenge it are met with the ire of conservative politicians and public opinion. These arguments about the past have such important implications for our understanding of the present. Often as not, patriotic narratives born of war mask dark deeds, past and present."

Approaching history from a Marxist perspective, a key theme of much of Markwick's research is the social underpinnings of Soviet society that meant, despite the appalling violence of the Stalinist state against its own people and supporters, so many remained loyal to it, especially during the Second World War.

"When people look at the collapse of the Soviet Union, they might express surprise it lasted as long as it did; considering its traumatic, violent history," he said.

"I have always been interested in the question of why this huge social experiment went so badly wrong. I have never been satisfied with answers that rested on the simple view that the socialist aspirations of the revolution were flawed from the beginning, or that it could all be explained by the diabolical character of Stalin."

One way he has attempted to answer that question is to look at the role of historical narratives, not only as instruments to stifle political thought, but also to critique or reinvigorate society.

In researching his PhD, Markwick was lucky enough to obtain extraordinary access to living Soviet historians and historical archives in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s.

Interviewing historians who had played such a crucial role under Khrushchev and Gorbachev was some of the most challenging and exciting research he has undertaken. His thesis, awarded in 1995 by the University of Sydney, focused on the role these historians had played. It also led to his book – Rewriting History in Soviet Russia: The Politics of Revisionist Historiography 1956-74 (Palgrave Macmillan 2001), which won The Alexander Nove Prize in Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies in 2001.

More daunting was the archival research required for his recent major book, the first comprehensive study of the military role of Soviet women in the Second World War, supported by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project grant.

With much of the sources involving military history, and given the centrality of 'The Great Patriotic War, 1941-45' to Russia, archival access was difficult if not impossible. However, with persistence Markwick was able to publish his book Soviet Women on the Frontline in the Second World War (Palgrave Macmillan 2012). Co-authored with Dr Euridice Charon Cardona, this book – which delves into why nearly one million women were willing to risk life and limb, seemingly in defence of such a draconian state – was shortlisted for a 2013 NSW Premier's History Award.

He has returned to this theme, this time looking at the motives and mechanisms that drove millions of Soviet women to labour in the most appalling conditions on the home front in the Second World War. Again supported by the ARC, this is a collaborative project with leading German historian Professor Beate Fieseler of Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Düsseldorf.

Markwick is passionate about history and the importance of the humanities and social sciences in general: "The humanities and social sciences not only equip people to be skilled members of the workforce but above all to be articulate, active citizens and participants in their own society."

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.