Researcher Highlights

Studying brain changes to better treat mental health

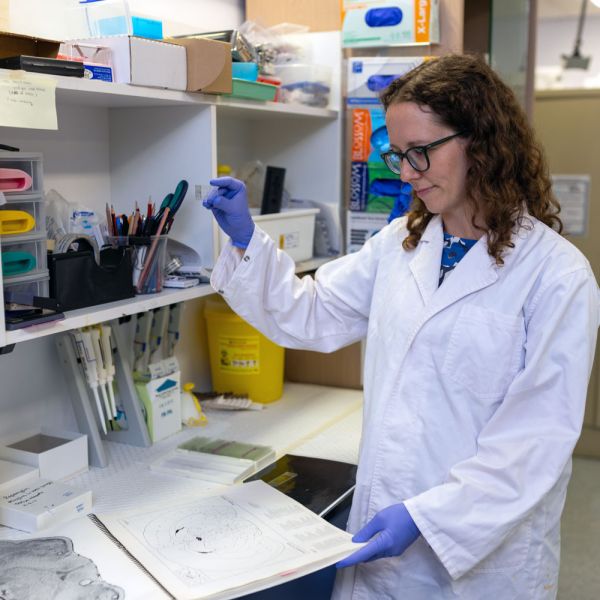

Dr Lizzie Manning

Neuroscience researcher and senior lecturer Dr Lizzie Manning is big on the brain, particularly its role in mental health. By carrying out research to understand neural activity, she hopes to create a future with more effective treatments.

Lizzie has always had an interest in how the brain works and mental health, in part sparked by having a sister with autism. She also saw friends and other family members go through mental illness and how difficult it is.

It was this interest that sent her on a journey into neuroscience research back in 2009.

After completing an undergraduate degree in Biomedical Sciences and a PhD in neuroscience at The University of Melbourne and the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health (The Florey)—the largest brain research centre in the Southern Hemisphere—she headed to the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh in the US to do her postdoc.

The department was very mental health-focused, and it was here that she began working in the translational obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) laboratory run by psychiatrist A/Prof Susanne Ahmari.

“I learned a lot from Susanne and how to bridge the translational gap between preclinical and clinical work”, says Lizzie. “I also gained new skills in in vivo calcium imaging and optogenetics, preclinical OCD models and operant cognitive paradigms.”

Developing an understanding of OCD

One of the unique angles they focused on in the US was how different aspects of inflexible behaviour arise in OCD.

“The obsessions in OCD can be understood as inflexible thoughts. These are anxiety-provoking thoughts that are really intrusive; people can’t just ignore them. Similarly, the compulsions are inflexible actions: patients can’t stop themselves from doing them. When you give people with OCD a psychological task, this can also be used to measure inflexibility in different aspects of decision-making,” says Lizzie.

To understand whether these different aspects of inflexibility in OCD share a common basis in the brain, they looked at animal models in her preclinical research to see if the brains of OCD models look different in terms of dysfunctional cells. As a result, they found mostly different patterns associated with repetitive, compulsive behaviours and decision-making.

After returning to Australia in 2020, Lizzie began working at the University of Newcastle. Two years later, when she was appointed to a continuing lecturer position, she started building on this research in her new lab.

To aid this work, she secured a sizeable Ideas Grant of $644,000 from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

But while in the US, she was focused on cells in the cortex (the grey matter or outer layer), she’s now headed south into the subcortical region, an area that’s really important for flexible control of behaviour.

Lizzie shares: “There are two subcortical pathways: one that tends to promote movements or actions, and another opposing pathway that tends to inhibit action. We’re trying to understand how balance between these two pathways is involved with different aspects of inflexible behaviour in OCD.”

The goal now is to dig a bit deeper into this.

Inflexibility across the mental health spectrum

The whole idea around inflexible behaviours is something Lizzie says is fairly broadly applicable across mental health, and her focus isn’t solely on OCD.

“For example, I’ve worked on other projects around inflexible behaviour, such as Tourette’s syndrome, a condition of the nervous system that’s closely related to OCD. People with Tourette’s have tics, which are difficult to control behaviours, so the way to understand it is similar.”

In another vein (or cerebral pathway!), she also points out the rigid, inflexible patterns of behaviour and decision-making seen in people with clinical depression. It’s not just an energy and motivation thing, she says.

“It can actually be a fundamental neural and decision-making change that happens.”

Stress and the hypothalamus

Her work around depression is linked to other research Lizzie is carrying out alongside Professor Chris Dayas, Assistant Dean Research and Innovation in the College of Health, Medicine and Wellbeing.

Chris’ interest is in the body’s central nervous system, which involves a lot of work on stress and the hypothalamus—a part of the brain that controls our stress hormone system, as well as hunger, body temperature, heart rate and mood.

“Together, we’re looking at what aspects of the brain control our responses to stress— how they become maladaptive—which contributes to stress-related mental illness, and how we can make them more adaptive. In other words, which brain changes underlie it”, she says.

In the group, they’re also looking at substance use disorders, such as illicit drugs and alcohol (see DECRA fellow Erin Campbell), and other inflexible behaviours involved in these disorders.

Digging deeper with other disciplines

These types of scientific collaborations are of huge value when it comes to digging into the brain. However, working with others doesn’t stop in the research lab.

Lizzie shares that understanding the organ in our heads isn’t just the job of neuroscientists. It also involves working with people with advanced skills in complex mathematics, engineering and other disciplines.

One such collaboration Lizzie and her team are involved in in Newcastle is with psychiatrist and computational neuroscientist Professor Michael Breakspear, who works at Hunter Imaging Centre. They also have a co-supervised PhD student.

“The benefit here is that they can help understand the brain and its complexity. It’s a mathematical understanding, modelling how the brain works and how neural activity changes give rise to behaviour changes.”

By working together, we hope to solve these big problems that haven’t yet been solved.”

A view to better treatments—and lives

The end goal for Lizzie and her teams of collaborators is to help people suffering from mental health-disorders that have traditionally been treated more superficially at a behaviour level rather than being treated as a disease of the brain.

“The hope is that we’ll be able to develop more targeted treatments that actually impact symptoms through specific neural activity changes. Currently, we tend to use things like antidepressants, which are fairly non-specific. While they do have some indirect effect on helping symptoms, they don’t cure people and are often associated with off-target side effects.”

By understanding the brain activity patterns that directly underlie these behaviours, they hope to develop drug treatments or brain stimulation therapy to normalise it.

In fact, some of the new research in Lizzie’s lab is interested in understanding how non-invasive brain stimulation, with a method called ‘transcranial magnetic stimulation’ (TMS), can impact the cells and pathways in the brain involved in inflexible behaviour.

Reducing stigma; increasing diversity

While the main part of Lizzie’s work is focused on the neuroscience side, she’s keen to share that she’s also committed to working on the stigma and misunderstandings surrounding mental health—something that can be a huge barrier to getting good treatments.

“We might develop the best treatment, but if there’s still some stigma and misunderstanding, it’s not going to get to the people that need it.”

In pursuit of this, she continues to ensure that new advances in understanding mental illness and the brain are shared more broadly with the community. For example, in the US, she helped establish an annual art exhibition featuring works from people with mental illness alongside works from scientists studying the brain. This helps get conversations happening.

In addition to the stigma, another challenge Lizzie mentions is the overall goal of improving academic equity. People from different backgrounds, including First Nations people, can bring fresh perspectives and experiences to research.

This is improving, and the University of Newcastle is a leader in equity and diversity in academia in Australia. But Lizzie hopes that by contributing to programs that allow a broader spectrum of people to do research looking at the brain, even greater progress can be made.

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.