Dust settled on the hot bitumen as Emma Austin and her PhD supervisor, Associate Professor Anthony Kiem pulled into the small town of Birchip in the Buloke Shire in western Victoria. After a 12 hour drive the heat engulfed them as they stepped out of the car.

“It was during that trip that we got chatting to the town’s school principal – a fella called John Richmond. He is a real champion for his community, the type of guy who brings people together,” Emma said.

In a town with a population of less than 800, John, unsurprisingly, wore a few hats and was also a coach for the local football club.

“He told us about a time at footy training with a team of kids aged around 8 or 9 years old.

“They were kicking the ball around the brown grass field. It started off just like any other training session.”

Confusion then trickled across the kids’ faces as expressions of fear sunk in.

Why?

It was raining.

"It was the first time in their lives that these kids had experienced rain."

"It was the first time in their lives that these kids had experienced rain. John told us they were genuinely terrified,” Emma recalled.

Buloke was one of the most drought-stricken regions across eastern Australia when Emma and Anthony visited in 2014. The ground had become so dry that there was not enough moisture in the soil to grow basic pasture to feed livestock.

"Farmers are faced with a devastating situation where they’re forced to slaughter their own cattle."

“When drought reaches that point, farmers are faced with a devastating situation where they’re forced to slaughter their own cattle. You can’t begin to imagine the toll this would take on their mental health,” Anthony said.

This scenario was one of many confronting stories that Emma and Anthony heard during their travels to towns in rural Australia. On a quest to understand the relationship between drought and wellbeing, the pair sought answers from the people who shoulder the burden of Australia’s harsh climate extremes.

They listened to and gleaned information from hundreds of farmers at the frontline whose livelihoods are determined by rain - or lack thereof.

Now, Emma and Anthony are funnelling that information into a tangible tool to help farmers get ready for drought – psychologically and financially.

They have teamed up with researchers from Southern Queensland University to create an Employability and Wellbeing Toolkit to support people in drought-prone areas.

Emma and Anthony are determined to harness the voices of farmers into a tangible tool

Dr Emma Austin's PhD research has helped inform the Wellbeing Toolkit

Associate Professor Anthony Kiem is the Director of the Centre for Water, Climate, and Land at the University

Turning the faucet on: a multifaceted challenge

Associate Professor Anthony Kiem is a hydroclimatologist and Director of the Centre for Water, Climate, and Land at the University of Newcastle. Based at the Newcastle Institute for Energy and Resources (NIER) – one of the University’s flagship research institutes – the Centre aims to understand and deal with the impacts of climate change and variability.

Anthony established the collaborative centre after the Millennium Drought when most of eastern Australia ran dry for close to 10 years – the worst drought on record for southeast Australia. It had become clear that hydrologists, meteorologists and land surface experts needed to work together – not in isolation – to give farmers the best chance to prepare for the next, inevitable drought.

“Drought is multifaceted and requires a multidisciplinary approach. Our centre brings the right mix of expertise and minds together,” Anthony said.

One of those minds is Dr Emma Austin.

During her PhD study at the University of Newcastle, Emma found that young farmers who lived and worked on farms in isolated areas, and were in financial hardship, were the most likely to experience personal drought-related psychological stress.

“We’re trying to reduce the stigma about mental health problems and overcome barriers that prevent people in rural areas from seeking professional help,” Emma said.

"It is the small, subtle things we notice which can provide clues that someone might be struggling."

“It is the small, subtle things we notice which can provide clues that someone might be struggling.

“A farmer might realise that a friend hasn’t been coming to social activities or church anymore. Or perhaps a neighbour has given up maintaining their property or repairing fences for example,” Emma said.

In these instances, Emma hopes the Wellbeing Toolkit will point to potentially life-saving resources on how to best approach and support people who are struggling.

A crippling catch-22

For people living in a farming or rural community, the majority of their income depends on the productivity of the farming sector.

“When a drought takes hold, the productivity in that town goes down. Then income goes down and often financial problems start to creep in,” Anthony said.

“Low employability affects mental health but if your mental health is already poor that affects your employability.”

Anthony hopes with the right resources and tools in place, they can help relieve farmers of this cruel catch-22 when drought strikes.

The toolkit’s key aim is to improve mental health and improve the diversity of income in rural communities.

Being an island continent, Australia is uniquely vulnerable to large-scale climate modes from the surrounding ocean. El Niño, which was officially declared by the Bureau of Meteorology on 19 September 2023, brings hot, dry conditions with below-average rainfall for most of eastern Australia.

"We can’t stop drought in Australia. We're always going to have droughts."

“We can’t stop drought in Australia. We’re always going to have droughts,” Anthony said.

“What we can do though, is learn how to better prepare for droughts.”

Thanks to advances in technology, Anthony explains that scientists can better foresee climate variability.

“We know several months in advance when a drought is going to happen so farmers can better predict if a crop will be successful,” Anthony said.

“This presents an opportunity for farmers to diversify their employment. Our toolkit will provide resources to do so.”

With mental health and employability closely intertwined, Anthony said diversifying sources of income helps strengthen mental wellbeing and increases an individual’s overall resilience to drought.

The Employability and Wellbeing Toolkit is one of 13 targeted projects which will form the Southern Queensland and Northern New South Wales Drought Resilience Adoption and Innovation Hub.

It’s one of eight Drought Hubs in Australia, each funded by the Commonwealth’s Future Drought Fund.

"Drought is not one size fits all. It occurs differently in different parts of the world, and especially in different parts of Australia."

“Drought is not one size fits all. It occurs differently in different parts of the world, and especially in different parts of Australia,” Anthony explains.

The strategic location of the hubs across Australia acknowledges that agricultural productivity differs immensely across the land, and drought resilience strategies need to be tailored accordingly.

The cost of drought

Cynthia McDonald, a farmer and councillor at Southern Downs Regional Council in Queensland shares the toll of drought in her community.

A two-way street: working with farmers to help farmers

The main aim of the Drought Hubs is to bring the latest science and evidence to the people who need it. But through years of research Emma and Anthony have found a major barrier with implementing effective drought resilience adaptation strategies is the disconnect between the information and end-users. That’s why they’re undertaking a co-design approach to develop their toolkit.

“We can write research papers until the cows come home. But they will just end up sitting on a shelf if we don’t engage with farmers and find out what’s working, and what’s not."

“We want to have genuine input from the people who are affected by droughts as to what would be helpful for them,” Anthony said.

“We can write research papers until the cows come home. But they will just end up sitting on a shelf if we don’t engage with farmers and find out what’s working, and what’s not.

Anthony and Emma will be run a series of roadshows and workshops with farmers to test and tweak the Employability and Wellbeing Toolkit.

“The hubs are like a matchmaking exercise,” Anthony explains.

“If a farmer has an idea, or a problem that they think could benefit from research expertise, there is a forum to pitch these.

“We want to hear about the problems farmers are facing, and also what they think about proposed ‘solutions’. Then we can put them in touch with researchers who have the expertise to help tackle these issues.”

A truckload ‘shipping container’ of water

While the Centre for Water, Climate, and Land is busily working on tools to help farmers psychologically and financially prepare for drought, across the road – also based at NIER – sits the Centre for Innovative Energy Technologies (CINET). Here, the team is engineering a physical tool to produce our most valuable resource: drinking water.

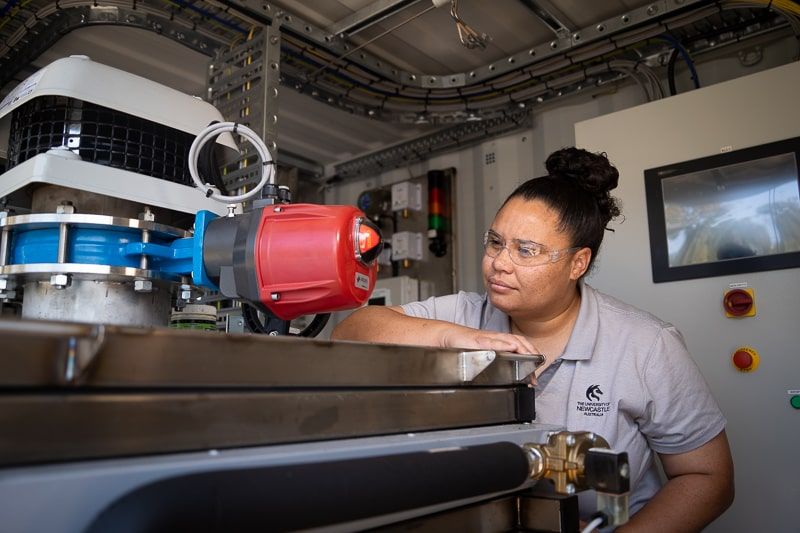

Dr Priscilla Tremain heaves open the door of an unassuming shipping container to reveal the impressive Hydro Harvester.

This machine extracts drinkable water from the atmosphere.

Bought a pair of shoes lately?

Priscilla, who is a chemical engineer, explains the Hydro Harvester uses similar particles to those found in the white packets to prevent mould in shoeboxes. You may have also spotted them in vitamin jars to protect pills from water damage.

“The particles absorb moisture from the air,” Priscilla explains.

“Solar energy or waste heat is used to produce hot, humid air – the hotter the air, the more water it holds.

“This hot air is then cooled using ambient air as a heat sink to extract water for drinking or irrigation.”

Priscilla and her team, led by Laureate Professor Behdad Moghtaderi, have secured $1.75 million in funding, also through the Future Drought Fund, to scale up the Hydro Harvester to produce 1000 litres of drinkable water a day. Their existing 100 litre model produces water at a cost of less than 5c per litre.

"Once we’re finished building the large-scale model, we’re hoping it can be deployed for use in communities suffering extreme water shortages."

“Once we’re finished building the large-scale model, we’re hoping it can be deployed for use in communities suffering extreme water shortages,” Priscilla said.

Priscilla Tremain pictured with the Hydro Harvester technology that can harvest water from thin air

The team is working on a large-scale Hydro Harvester to produce up to 1000 L of water a day

Dr Priscilla Tremain with the small-scale Hydro Harvester at the University of Newcastle

The water thief

Cynthia McDonald (featured in the video above) is a farmer and councillor at Southern Downs Regional Council in Queensland. She has witnessed how drought relentlessly steals water from cattle, sheep, crops, and people.

"When a drought takes hold, it’s almost like a creeping cancer. It starts to disable the community bit by bit by bit and grows."

“When a drought takes hold, it’s almost like a creeping cancer. It starts to disable the community bit by bit by bit and grows.

“We got to the point where farmers were out of water so they couldn’t even shower or flush their toilets,” Cynthia said.

Cynthia lives near the town of Stanthorpe in Southern Queensland, where in 2019 the town’s water supply was so dire that drinking water needed to be continuously trucked in. She’s seen first-hand how valuable a tool like the Hydro Harvester would be.

“As a farmer, I don’t think that we’d be going backwards in coming forward to accept and embrace that type of technology in the region,” Cynthia said.

“In an agricultural region I think it could be a gamechanger,” Cynthia said.

While Priscilla and her team can’t make it rain, they hope their technology will turn the tap on when it’s desperately needed. And while Emma and Anthony can’t stop drought, they hope to lighten the load of the people who shoulder the pain of Australia’s harsh climate.

It's time to turn the tide on drought.