Readers are advised that this feature contains confronting and distressing information.

In her small and quaint Cooks Hill apartment, its walls overflowing with books from floor to ceiling, renowned historian Emeritus Professor Lyndall Ryan, AM takes a moment to reflect.

For the past eight years the 79-year-old and her research team have upheld an unwavering commitment to uncover and confirm the truth about Australia’s early colonial history.

It’s been an endeavour that has unearthed confronting and deeply disturbing details of the colonial frontier massacres of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The research project’s fourth and final stage’s recently released findings now estimate more than 10,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s lives were lost during at least 414 massacres committed during the period 1788 to 1930.

Evidence also shows around half the frontier massacres were carried out by colonial officials, such as police and soldiers, either solely, or in conjunction with settlers and/or their employees.

And unexpectedly, the attacks during the spread of pastoral settlement in Australia did not decrease as the decades passed; they intensified. More massacres occurred in the period 1860 to 1930 than in the earlier period of 1788 to 1860.

It’s a very different version of early colonial history from the one older Australians were taught during their school days.

However, it’s a truth that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have always known – and a truth that has produced lasting trauma.

“It's clear that my generation has been protected from this kind of information and when I do talk to people of my generation about these events, they're incredibly shocked,” University of Newcastle researcher Professor Ryan said.

“Some people don't want to know any more, but many others do.

I find that a younger generation of school children do want to know what happened and do want to make amends.”

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia research

Truth-telling education for Australia’s next generation

The prime focus of the Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia research project has been to map massacres with supporting historical evidence and make it publicly available.

The map is now on permanent display at the Australian Museum in Sydney and is starting to appear in a number of other public locations. Journalists, authors, primary and high school teachers, universities and university students; and Aboriginal people and organisations have asked to re-use the map and its data.

For Professor Ryan, it is a video message from a group of South Australian school children, who studied the map and filmed their visit to a local massacre site, that demonstrates the project’s important truth-telling role in educating the next generation of Australians.

“We're finding that this new information in the map project is becoming embedded in the school curriculum. So that’s a big step forward and I think it's helping us to change our understanding of the past,” she said.

The project’s online map and database records details of each verified frontier massacre in Australia between 1788 until 1930, including the massacre site locations and the sources corroborating evidence of the events.

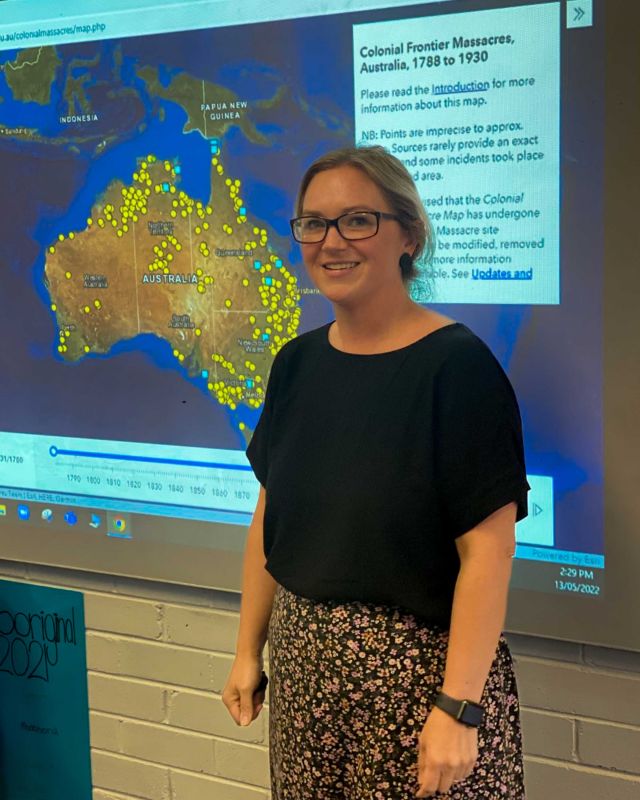

When Gorokan High School Aboriginal Studies teacher and proud Dharawal woman Jessica Sanchez learned of the massacre map project through a colleague, she instantly recognised the role it could play in the classroom.

“As teachers we're always looking for more information, resources and knowledge. I think the map’s an invaluable resource. Because I have a strong focus on the impact of colonisation within my content, it just works brilliantly with it, giving it a visual aspect.

“We'll look at it together and study the different massacres around Australia, talk about the different mobs, the impact, how many people died - from both sides, and then they'll do some additional research.”

For some students, learning the extent of the truth is confronting.

The map triggers varying reactions from students, many of whom are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people.

“The very first thing they're always confused about is ‘how did it happen?’ Why and how did it get to a point where so many people died and what was the background behind it?

“It sparks a lot of responses like ‘I can't believe that happened’.

"They're very shocked and very disheartened that something like that would occur.”

Mrs Sanchez said Aboriginal community members from the school’s Aboriginal Learning Engagement Centre were often in the classroom to offer extra support when difficult discussions surfaced.

“It is hard for some students to hear the truth.

“I don't think anyone could put their hand on their heart and say they knew the extent of the massacres across Australia,” Mrs Sanchez said.

The extent of the truth

When the debate about frontier massacres began in the media about 20 years ago, Professor Ryan said the questions included, “were frontier massacres widespread across colonial Australia, or were the massacres few and far between, that they were an aberration; they very rarely happened?”

Professor Ryan began her research testing that hypothesis.

“I've found many more massacres than I ever imagined happened.

I thought there might have been a couple of hundred at the most and that each had not only its own story, but each was very different. And each, in a sense, happened because of very strange circumstances.”

The research project confirmed the massacres were widespread, followed the frontier across Australia, and were very carefully planned.

“They weren't an accident. They were designed to get Aboriginal people out of the way, whether it was to ‘teach them a lesson’, or to make them so timid that they were easier to turn into slave labour,” she said.

For example, a large massacre that occurred in western Queensland around 1900 targeted a ceremony of Aboriginal people. The perpetrators gathered several days beforehand and as the ritual was ending, they ambushed and shot as many Aboriginal people as they could.

A massacre in the Kimberley in the 1890s saw Aboriginal men captured and secured with neck chains. The men believed they were being taken off to town. Along the way, it was decided the group would camp for the night.

“Even in their neck chains they were sent out to gather firewood,” Professor Ryan said.

“When they brought the firewood back, the perpetrators poured kerosene or some other fuel on the fire and threw the Aboriginal people into it. That's a frightening massacre, and certainly one of the worst we've ever come across,” she said.

“So, they're becoming better organised, they're becoming more brutal, they're becoming more frightening to read about, and, I feel, more frightening for the survivors as well,” she said.

“The overall purpose was to reduce the population of Aboriginal people in Australia and keep them away from infrastructure such as telegraph lines and natural features like large water holes, so that cattle and sheep would have ready access.”

Evidence versus the code of silence

The historical records reviewed by the team, including colonial diaries, newspaper reports, Aboriginal evidence and archives from State and Federal repositories, often included archaic terms that were both racist and offensive, as well as themes and content that were highly distressing.

Throughout the investigation the research team received hundreds of messages via the map’s website providing feedback on the data published at each of the project’s four stages, and in some instances, crucial family archives that contained proof of massacres.

Yet it was Australian newspapers, stored on the online resource Trove, that formed the major source for the project, with more than 90 newspapers from every colony, state and territory consulted. Professor Ryan said newspapers often provided the first reports of a frontier massacre and reports of official inquiries into a ‘possible massacre’.

“They can also provide, many decades later, the voices of the attackers and survivors who tell their story long after the event.

“For this reason, the most reliable sources of evidence are often found in secondary sources, when fears of arrest or reprisal have long passed.”

While some frontier massacres were widely publicised, in most cases a code of silence was imposed in colonial communities in the immediate aftermath. Frontier massacres were only referred to indirectly.

According to The Queenslander, 1 May 1880, p.560, the ‘bush slang’ word ‘dispersal’ was often used as a convenient euphemism for ‘wholesale massacre’. Other euphemisms such as ‘clear the area’, ‘pacify’ ‘teach them a lesson,’ ‘affray’ or ’fell upon’ were also used.

Investigating events in Western Australia, Professor Ryan said newspaper reports were far more reliable than official police reports.

“The police report will tell you how many people were in the group, when they went out and when they came back, but they won’t tell you very much about what happened in between. But they will say how much ammunition they expended.”

However, a member of the perpetrating group would often write a report that's published in a newspaper far from where the massacre occurred, sometimes across the country.

“The report will often say ‘we set off with Constable X and we came across these groups and we fired at them – we decided to attack the camp early in the morning’ or ‘we decided to attack that camp at night because they were having a ceremony’.”

Professor Ryan said a number of large massacres in the southwest of Queensland were organised well ahead of the arrival of Aboriginal people who came in from a wide area to have a major ceremony.

“And they shot them all. They are getting pretty gruesome and often those newspapers are quite open about it. I was astonished,” she said.

What was learned about frontier massacres?

- A frontier massacre was usually a planned rather than a spontaneous event

- The attackers and victims often knew each other

- A frontier massacre was a one-sided event in that the victims were relatively undefended

- Frontier massacres were usually carried out by a group of attackers, rather than a sole attacker.

- A frontier massacre was usually carried out in secret with no witnesses intended to be present.

- In the immediate aftermath, a code of silence was imposed by the attackers, making early detection extremely difficult. The attackers and their supporters usually denied that a frontier massacre had taken place or that they were involved

- The most reliable evidence of frontier massacre is often found in sources long after the event when fears of arrest or reprisal have long passed

- In some cases campaigns of mass killing by a specific group of attackers against a particular group of Aboriginal people were carried out over a wide area over several days or longer and so are part of a group or series of massacres. These series of massacres, carried out by the same group of attackers, have the intent of eradicating Aboriginal people from the area.

Confessions rise to the surface

The code of silence that surrounded colonial frontier massacres appeared to weigh heavily on some who later confessed, sometimes decades after the acts of violence were committed.

In the 1850s a wealthy Victorian settler wrote a letter to the governor explaining how he and a number of his workers were ‘suddenly surrounded by Aboriginal people early one morning and they had to shoot their way out’.

“About 40 years later, a journalist from the Melbourne Argus is following a Victorian politician out to the Northeast, where there's talk about where the new railway line will go. Everybody wants the railway line,” Professor Ryan said.

“He lands in town and goes into the pub where someone says a retired shepherd wants to talk to him. He arranges to meet the shepherd and he says, ‘I want to tell you what really happened’. Obviously, he wanted to get it off his chest.

“In his anxiety to actually tell the truth, he points out that it was a very well organised event in which it wasn't about self-defence; it was about killing people and getting them out of the way.

“You do get people having the need to tell later on. They kept quiet at the time.”

In 1827 a group of Aboriginal people near a NSW property on the Patterson River were corralled into a swamp and shot.

“It is reported in the local press at the time, and it's almost word for word in the official report that goes down to Sydney. However, in the early 1870s the Maitland Mercury interviews the man who was the overseer of the property. The property owner had just died, and the overseer felt he could now say what really happened.

“So, there’s this constant hiding. This code of silence is universal throughout Australia,” Professor Ryan explained.

Findings confirm what our people have always known

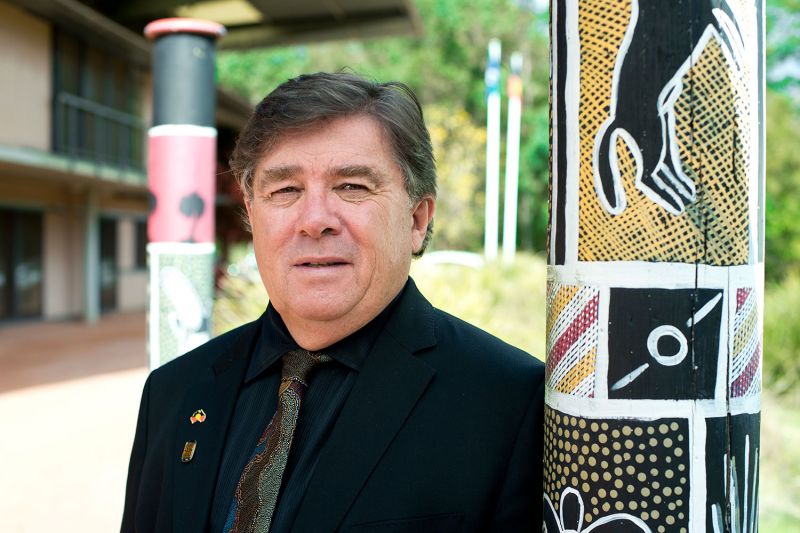

Worimi man and Aboriginal historian at the University of Newcastle, Emeritus Professor John Maynard, said the 414 massacres confirmed through the project was the tip of the iceberg.

“It was important these events were substantiated and brought into wider understanding. However, it is something our communities and people have always known,” Professor Maynard said.

“There was a deliberate process of erasing these events from Australian history and memory.

“I came through a school system of the 1950s and 1960s where we were not in it. In saying that, it is critically important that all students can understand these events and then hopefully, down the track, we can join hands and walk on to a shared future that recognises all Australian people.”

Professor Maynard believes lessons about colonial frontier massacres should be embedded in schools’ curriculum and given the same recognition as Gallipoli, Tobruk and the Kokoda Trail.

“It is important the project and its findings are made and promoted as widely and accessibly as possible.

“We need a balanced understanding of the past and colonial frontier massacres and warfare should be incorporated into the curriculum to aid that process.”

He said it would make a significant difference to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to have a more truthful history about colonisation taught in schools.

“I am hoping that the next government takes the important step to introduce a truth telling process for the country,” he said.

The path forward

Professor Ryan and her research team openly acknowledge the mapped massacres do not paint the full picture of colonial frontier violence.

“We know frontier massacres were often covered up and, while we only include massacres with supporting evidence, the details of accounts can vary and be imprecise. Future research may reveal further information,” she said.

“We need to know what happened. And we need to know more.”

For now, it is hoped the mapping project inspires more truth-telling and becomes part of Australia’s narrative to help find a path forward.

The Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia map is available at https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres. The project is funded by an Australian Research Council (ARC) grant investigating Violence on the Australian Colonial Frontier, 1788-1960. Professor Ryan is a member of the University of Newcastle’s Centre for 21st Century Humanities and the Centre for the History of Violence in the College of Human and Social Futures. The team also includes Dr Jennifer Debenham, Dr Chris Owen, Dr Robyn Smith and Dr Bill Pascoe.