When Daryn McKenny walks through the bush at night, he isn’t just exploring – he’s searching for “tree stars.”

“Their eyes are bright white, and they look just like blinking stars in the trees,” he says.

“Kewala!” Gualawin!” he calls, peering up at the canopy of a eucalyptus tree.

“I’m introducing myself to the koalas. That’s when they look down and you get to see those tree stars,” Daryn says, smiling.

Watch the full story

Kewala means female koala in Awabakal Indigenous language

Gualawin means male koala in Awabakal Indigenous language

A Gamilaraay and Wiradjuri man, Daryn grew up in Killingworth, a suburb which borders Sugarloaf State Conversation area in NSW.

“Sugarloaf was practically my backyard as a kid,” he recalls.

“We were always riding our bikes around the bush. I never saw koalas though…because we never looked up.”

It was five years ago when Daryn first spotted a koala in Sugarloaf. From that moment, he was captivated by these mysterious marsupials. Now, as an Indigenous scientist, he spends hundreds of hours observing the secret lives of the Sugarloaf koalas.

He sets up discreet, motion-activated trail cameras, capturing glimpses of the animals as they move high in the trees but more often, surprisingly, roaming the bush floor.

Daryn recalls he was at home, trawling through hours of footage when he realised he’d captured a koala at Sugarloaf on camera – for the first time.

“I live in an apartment building, I’m pretty sure my neighbours on all levels would have heard me screaming.

“It was a mother with a baby on her back. That made it even more special,” Daryn says.

Daryn's trail camera footage captures rare glimpses into the lives of Sugarloaf's koalas

As his monitoring continued over the years, Daryn began to recognise individual koalas, especially the mothers who he spotted on camera, year after year. One female, in particular, became unforgettable.

“I named her Tankaan, an Awabakal word honouring her as a mother, after observing her raise at least three joeys across subsequent years,” Daryn recalls.

Watching Tankaan move through the seasons – carrying a tiny new joey one year to guiding a confident youngster the next – offered Daryn a rare glimpse into the generational storylines unfolding in Sugarloaf.

Little did he know, Sugarloaf would turn out to be home to an estimated 292 koalas – an amazingly large population that had never been officially documented.

Eager to learn more about the koalas he was uncovering, Daryn reached out to a team of conservation scientists at the University of Newcastle.

Dr Ryan Witt admits he was surprised by the extent of Daryn’s evidence which pointed to a potentially large, even stable, population in Sugarloaf.

“There had been a few sightings here and there, but no official records of a large koala population in Sugarloaf,” Ryan says.

“The nearest koala population we’d found was small – in Stockrington State Conservation Area which borders Sugarloaf,” he says.

Koalas are notoriously hard-to-detect, hidden high in the tree canopy.

“That makes understanding their populations incredibly difficult,” Ryan explains.

But it hasn’t deterred Ryan and his team. Since 2020, they’ve spent more than 250 nights – or 10,000 hours collectively – surveying for koalas to monitor and track populations.

Before thermal drones, researchers searched for those elusive “tree stars” on foot at night with a spotlight – a slow, painstaking process, and that was often impossible in steep, rugged terrain like Sugarloaf.

“Accessibility is a real challenge in areas with sloped terrain, which makes tracking koala populations difficult,” Ryan says.

Finding a koala in less than two minutes

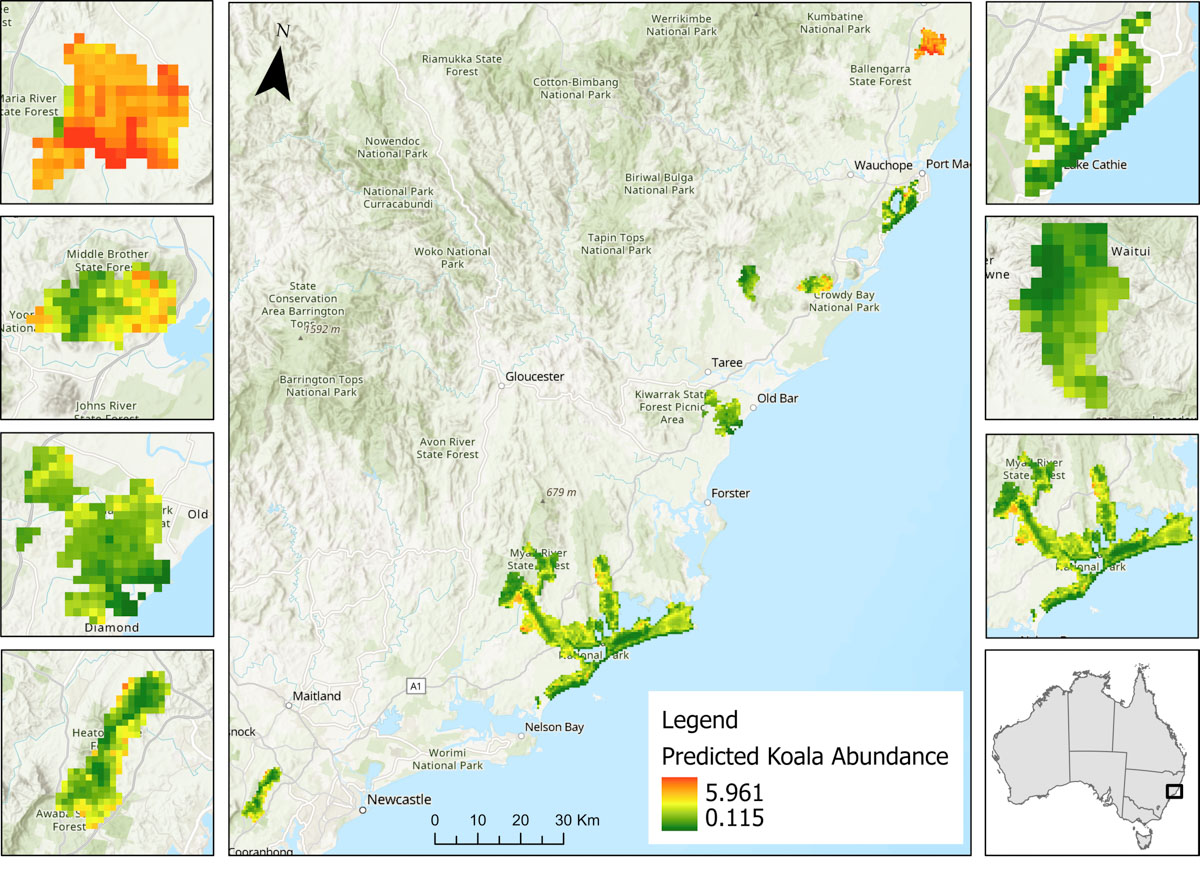

To estimate koala populations more accurately, Ryan and his team developed a new world-first approach.

To estimate koala populations more accurately, Ryan and his team developed a new world-first approach.

Shelby Ryan, a PhD student leading the study, explains how they set out to estimate the true number of koala population sizes.

“It's really important to establish a baseline because then we can understand changes to the population over time with threats,” Shelby says.

Thanks to Daryn’s insight, Sugarloaf State Conservation area was included in surveys across seven reserves in NSW. Using a thermal drone with a spotlight, the team could locate and verify a koala in less than two minutes – a process that once took hours.

They conducted surveys at night during winter, when koala’s body heat is easier to detect. A yellow dot on the screen would point researchers to potential sightings.

“We steer the drone towards heat spots and switch on the spotlight to check whether it’s a koala,” Shelby says.

Their study revealed Sugarloaf is home to an amazingly large population of 292 koalas.

“This population has flown under the radar – proving that koalas can survive, and even thrive, in peri-urban areas,” Ryan says. “These fringe habitats need protection and monitoring just as much as pristine reserves.”

Of the seven national parks surveyed, Maria National Park had the highest density with 521 koalas predicted in 3,350 hectares. But Ryan cautions “density doesn’t always reflect a thriving koala population.”

The team also surveyed two areas that were burnt in the 2019-20 Black Summer bushfires – Lake Innes and Khappinghat. They found the abundance of koalas at fire-affected sites was about two-thirds less than unburnt sites.

Combining Indigenous knowledge and Western science

The research team worked closely with Daryn to survey Sugarloaf. His deep understanding of the land helped build a fuller understanding of koalas in the area.

“Daryn has so much knowledge of the environment that we would never have learnt without working with him,” Ryan says.

“We were grateful to learn from him and in turn share our methods of finding these cryptic animals,” Ryan says.

Daryn’s targeted monitoring techniques and intimate knowledge of koalas at Sugarloaf complements the large-scale monitoring approach of the research team. And as for Daryn’s koala tracking skills, Ryan says “I’ve never seen anyone scale Sugarloaf as fast as Daryn. He had already found many koalas before our research even began.”

Dr Ryan Witt and Daryn McKenny at Sugarloaf State Conservation Area

Dr Ryan Witt and Daryn McKenny pictured with a thermal drone

The thermal drone is fittingly named 'Marcia' after a Blinky Bill character

Daryn strategically secures a trail camera next to a Eucalyptus tree to record koala movements

For Daryn, he says the collaboration was just as meaningful.

“What the University team brought to this space was incredibly powerful," Daryn says

“To now know there are 292 koalas here is just incredible,” he says.

Daryn explains “for Aboriginal people, story is data.”

“By combining Aboriginal story and Western data, we’ve painted a much fuller picture of Sugarloaf’s koalas. Hopefully this information will contribute to protecting them,” Daryn says.

A new era for wildlife monitoring

The study sets a new global standard for monitoring tree-dwelling mammals.

“This kind of scale and precision is unparalleled in conservation,” Ryan says.

“We can now estimate how many animals are out there—and where—even in areas that are hard to access.”

Knowing where koalas are is crucial information to protect the endangered species. WWF-Australia funded the research for this reason, and because it supports their goal of doubling number of koalas in eastern Australia by 2050.

Darren Grover, WWF-Australia’s Head of Regenerative Country, says “achieving accurate abundance estimates is the holy grail of koala conservation.

“The work of Dr Witt and his team shows great promise towards that goal,” Darren says.

Back under the gum trees, Daryn still searches for tree stars.

“When those eyes blink down at you,” he says, “you know Country is alive.”

They will forever be a reminder of Sugarloaf’s best kept secret.

The study was published in the journal, Biological Conservation. It was funded by WWF-Australia and led by the University of Newcastle in collaboration with researchers from Taronga Conservation Society Australia, UNSW, and FAUNA Research Alliance.

Aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

Related articles

Could freezing koala sperm save the species?

A team of conservation scientists are banking on IVF technology to protect Australia’s endangered koalas long-term and preserve precious genetics.

Read more

“I thought I was a bad mother”: How telehealth changed a young boy’s life and gave a family hope

“I thought I was a bad mother,” says Marlie Matthews, tearfully. “I tried everything, but Marcus was getting more and more behind. He wasn’t speaking much and when he did, I couldn’t understand him. It was very hard on all of us.”

Read more

A leap of faith

Citizen scientists are teaming up with University of Newcastle researchers leading Australia’s effort to prevent the extinction of precious amphibians.

Read more