British ships carrying plants and seeds from around the world arrived in Botany Bay on January 20 1788. This story is overshadowed by convict ships and Royal Navy vessels, but the cargo on board also had a lasting impact. Colonists, convicts and Indigenous Australians were all affected when new species transformed the landscape.

British colonists introduced plants as foreign as the people who carried them. Some of these plants, ranging from bananas to wheat, were food sources, promoting self-sufficiency.

Others were attempts to expand the British Empire.

Could the new territory be exploited as a tropical plantation?

Botanical imperialism

In the parliamentary debate over destinations for convict transportation, Sir Joseph Banks and James Matra, both members of James Cook’s 1770 expedition, spruiked the potential of the new colony as an extension of the empire.

Matra claimed the colony was “fitted for production” of “sugar-cane, tea, coffee, silk, cotton, indigo and tobacco”.

Banks claimed Botany Bay was an “advantageous” site, with fertile soil – and virtually no inhabitants.

Two plants carried by the First Fleet stand out as examples of botanical imperialism: prickly pear cactus (Opuntia) and sugarcane. Banks, as head of the Royal Society of London, selected these species as experiments to compete with European trade rivals.

His goal was to break a Spanish monopoly in producing fabric dye and to expand British cultivation of sugar outside the West Indies.

The secret of the colour scarlet

Prickly pear cactus was imported because it is the preferred food of the cochineal insect. Dried cochineal were crushed to make a vibrant, colourfast scarlet dye for textiles. Discovered in the New World by Spanish colonists, cochineal replaced kermes, another insect that had provided red dye since antiquity.

Cochineal dye was ten times stronger than kermes or vegetable dyes. From cardinals’ capes to British officers’ red coats, cochineal was a product for elite consumers signifying power, wealth and prestige.

New Spain, based in Mexico, had a monopoly on cochineal. Banks wanted to break the stranglehold on the scarlet dye by establishing production in New South Wales. Plants infested with the precious insects were imported from Brazil in 1788.

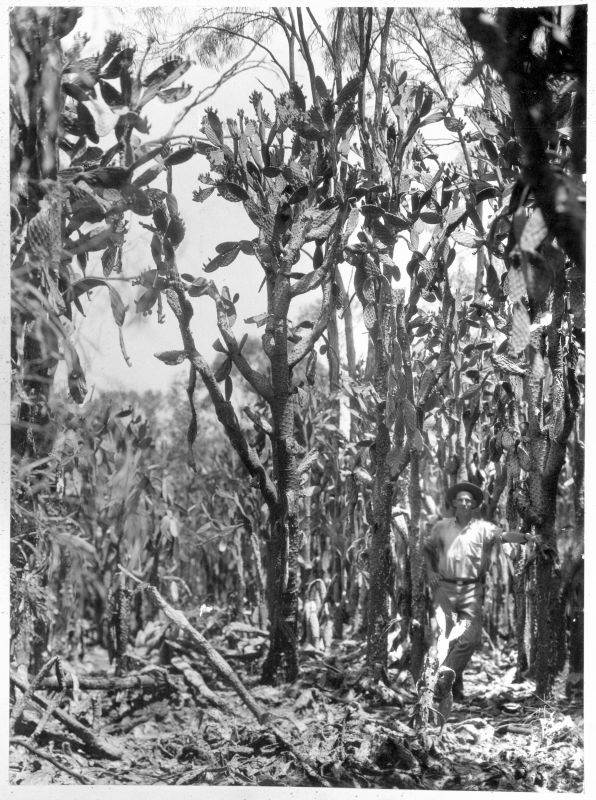

The project soon failed when the cochineal died, but the cacti survived. Colonists used cacti as natural fences and drought-resistant animal fodder. Without insects to feed on them the plants spread, uncontrolled, to cover more than 60 million acres of eastern Australia by the 1920s. Poison, crushing and fire failed to stop the cactus.

In 1926, a moth species from Argentina was introduced to eradicate the plants, but Opuntia cacti remain an environmental hazard. Trade in the plants, classified as weeds of national significance, is banned in most states.

Related articles

The secret lives of Sugarloaf koalas

“Tree stars” in the night sky revealed a hidden koala colony, nestled deep within Sugarloaf’s bushland.

Read more

Tackling the chemicals we can’t see: PFAS

PFAS contamination is persistent, but so is the determination of scientists working on solutions to remediate it.

Read more

Why are sunsets so pretty in winter? There’s a simple explanation

If you live in the southern hemisphere and have been stopped in your tracks by a recent sunset, you may have noticed they seem more vibrant lately.

Read more

Air is an overlooked source of nutrients - evidence shows we can inhale some vitamins

You know that feeling you get when you take a breath of fresh air in nature? There may be more to it than a simple lack of pollution.

Read more

Conservative governments protect more land while socialists and nationalists threaten more species

The dire state of biodiversity across the globe suggests not all governments are willing to act decisively to protect nature. Why is that the case, and is a country’s political ideology a factor?

Read more

Bold climate action benefits more than just the environment - it's also great for business

As the world grapples with the intensifying challenges of climate change, businesses are under increasing pressure to take action.

Read more

The first sugar grown in Australia

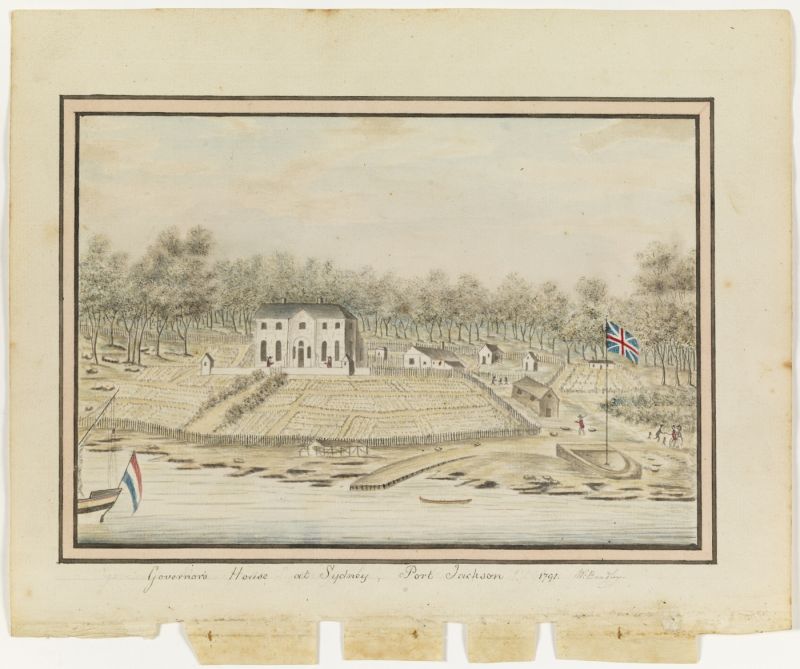

Sugarcane was imported from the Cape Colony, now South Africa. Before sugar was planted in Queensland, or even Port Macquarie, in the 19th century, sugar was grown in a small garden plot in Sydney and as an experimental crop on Norfolk Island in 1788.

The Royal Navy targeted Norfolk Island as a source of flax and timber, but it also served as an agricultural laboratory, testing tropical crops like sugar and coffee for Banks.

Philip Gidley King, lieutenant-governor of Norfolk Island, reported in his correspondence with Banks in 1790 that his four canes had multiplied into more than 100 plants. Within a few years he sent samples of sugar, rum and molasses to Sydney. By 1798, the cane was declared “prolific” and Norfolk Island was in “a state of cultivation equal to the West Indies”.

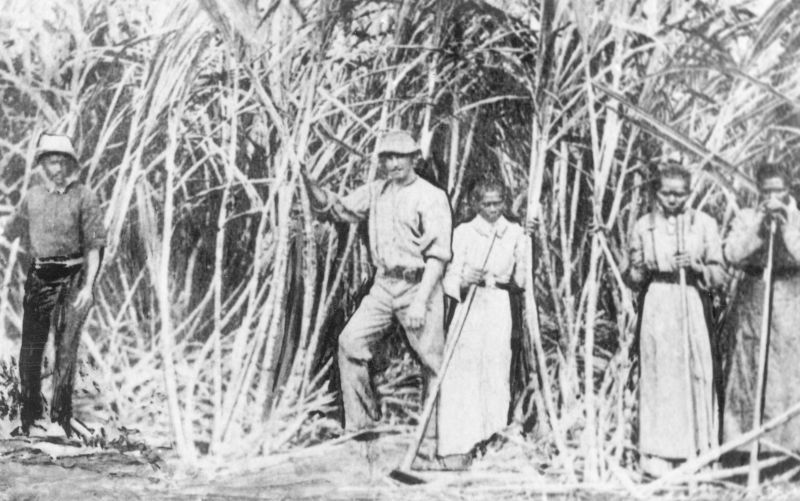

This favourable comparison with the West Indies ignores the use of convict labour in producing sugar, and foreshadows the advent of “blackbirding”, a euphemism for the abduction or coercion of Melanesian workers. Blackbirding was introduced in Queensland canefields in 1863 as penal transportation ended and cheap convict labour became unavailable.

Once essential to the sugar industry, in 1901 Pacific Islanders in Australia were deemed undesirable, competing unfairly with white workers. As part of the White Australia Policy, many were deported under the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901.

The fruits of empire

Reconsidering the impact of alien plant species on Australia gives us additional insight into the process of colonisation.

Transplanting species from around the world to create a new environment was a major endeavour in the 18th century, and a manifestation of imperial power and control.

Indigenous connections with Country were disrupted when foreign botanical landscapes displaced native species. The roots of these early imperial projects are deeply embedded in Australian culture and history, with an enduring legacy.

Header image from the Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.