University of Newcastle staff member, Leanne Elliott, sits quietly at a table at the Wollotuka Institute, armed with her laptop.

The central foyer where she waits is named the ‘Birabahn room’ - A large mural of an eagle-hawk is vibrant underfoot, stretching its wings across the sunlit meeting place.

Located at the Callaghan campus on the lands of the Pambalong clan of the Awabakal nation, the Birabahn or eagle-hawk, is a sacred totem to the Awabakal people and is the name of a well-known Awabakal leader and scholar.

It is a fitting reminder of the unbroken importance of community, as Leanne endeavours to learn the histories of her own family.

While it’s already been a journey to get here, she is confident the pieces of her ancestry puzzle are slowly falling into place.

"There was always whispers growing up but nothing really was said, and we kind of weren't meant to talk about it or ask questions,” Leanne explained.

“Before my grandma passed away, we discovered a couple of photos… And we started asking a few questions that grandma was kind of happy to answer.”

Leanne’s unfolding story of learned heritage is not uncommon.

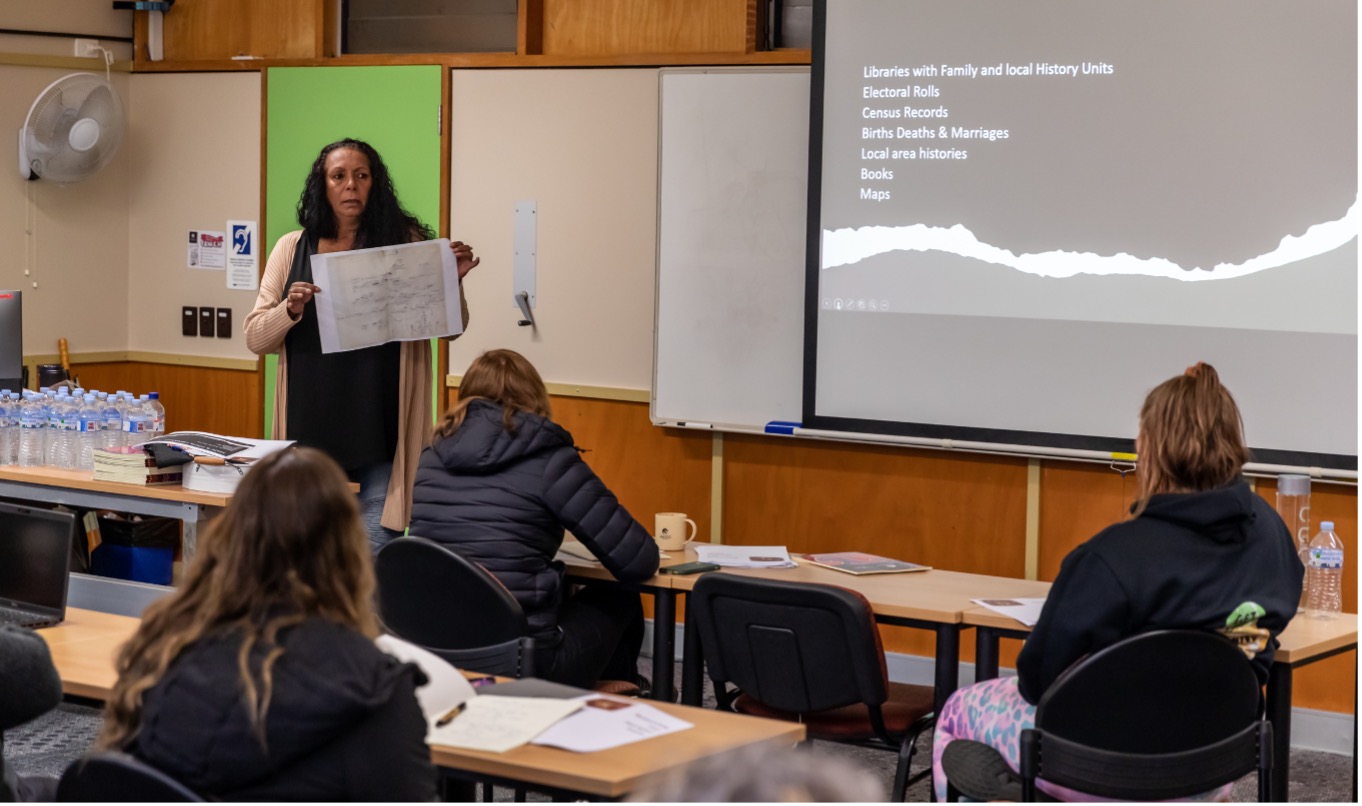

A new workshop guides participants like Leanne Elliott (pictured) on a journey to connect with First Nations identity and history.

Targeted, forceful, and deliberate attempts by successive governments since colonisation have disconnected and distorted Aboriginal family lines - For many, to an untraceable extent.

These barriers were a clear consideration for the University of Newcastle when creating guidelines for confirming Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status; a process required for specific services such as identified scholarships and professional roles.

To this end, a new workshop has been created to help people, including Leanne and other University students and staff, to know their history and connect with their communities.

"I can go and research all my ancestry online but connecting with the culture is a whole different ballgame,” Leanne said.

“I wish this workshop had been available a long time ago, I think it's a great resource for people in general who would like to find out more and just kind of don't really know where to start.”

Community Connections

Facilitated by the University of Newcastle’s Wollotuka Institute, the Family Tracing workshop is a culturally appropriate and sensitive program that assists in researching First Nations ancestry.

The session is a crucial part of the University’s over-arching goal: To create a best-practice model for tertiary institutions in ensuring identified opportunities are for First Nations people.

Accountability and a holistic approach is being fiercely prioritised by Wiradjuri man and Pro Vice Chancellor of Indigenous Strategy and Leadership, Nathan Towney.

“We want to, as a University, help people understand the complexities of identity… but then also give them the tools and the strategies to try and reconnect back into the communities where their family originate from,” Mr Towney said.

The first workshop was attended by representatives from universities across the state, hoping to witness the benefits of the unique program.

It compliments both the policy and procedure for ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander - Establishing Status within the University,’ a recently-refined process that was needed to meet community expectations.

The University’s policy is in line with the Commonwealth, defining Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to be 1) of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander descent, 2) identify as such, and 3) be accepted by their First Nations community.

For participants who are able to trace their family lineage, the University has allocated resources to help explore community connections – whether it be through further research, consultation or assistance to physically link up.

“What we're trying to do through this process is help people understand the importance of that third criteria, and the complexities around that third criteria, and then also give them the first steps to help them meet that,” Mr Towney said.

“It's really important for us that we have the structures and processes to ensure that programs and activities that are set aside for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are actually used by and accessed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.”

While there is support available for all First Nations students at the University of Newcastle, the confirmation process is only required for specific opportunities.

To re-enforce the focus on community accountability, the application process will also be witnessed by a panel to ensure legitimacy, with the final decision sitting with Mr Towney in his executive role.

Streamlining the process is also a priority, migrating applications to the online student portal so records are kept across campus programs, and individuals will not be needed to re-confirm their Aboriginality unless an audit is required.

“Stories are preserved and heard”

University of Newcastle understands the sensitivities around family, community expectations, and identity, and has created a service that is supportive through each outcome of this journey.

The process is a product of many years of consultation and reflection.

Staff, students and future students won’t be alone in their learning, while the University continues to uphold the standards required for recognised Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status.

By using online and practical resources, participants in the Tracing Family workshop are guided by Gamilaroi woman, Allison Trindall, to navigate a search through family history.

From understanding genealogies, to the permissions needed when accessing state archives – this important service is a support available to those who are looking to know more about their ancestors and themselves.

As the workshop facilitator, Allison has more than 20 years’ of experience researching and connecting Aboriginal families, having worked with peak Aboriginal research organisation Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) and assisting members of the Stolen Generations to link up with their mobs.

“Researching and recording your family’s histories for yourself and future generations will ensure our heritage and stories are preserved and heard for years to come,” Allison Trindall said.