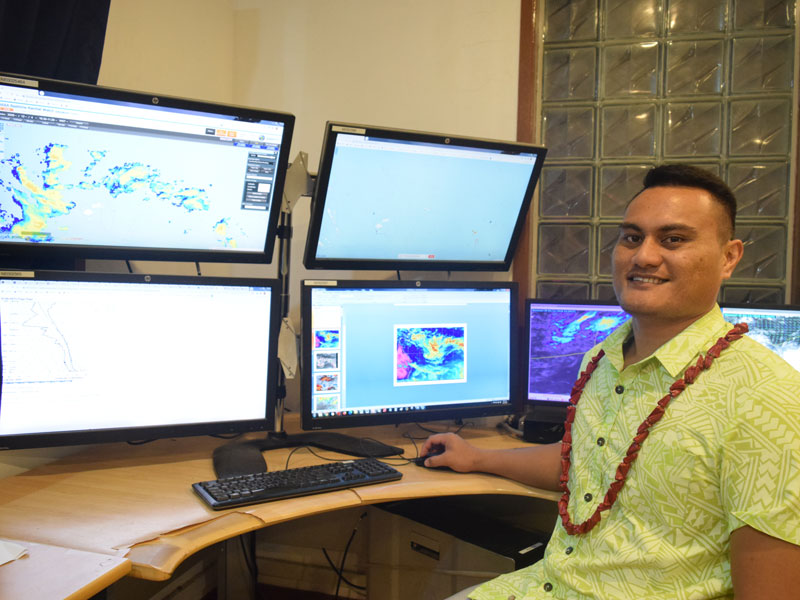

In June 2012, Silipa Mulitalo had just started a new job as a Meteorologist at the Samoa Meteorological Service. A few months later one of the worst cyclones to ever hit the country wreaked widespread havoc across the capital, Apia.

Declared a Category Three event, Severe Tropical Cyclone Evan brought with it wind gusts of up to 210 km/h, intense rainfall and caused almost complete failures in the power and water supply systems.

It lasted for five days and left in its wake absolute devastation, including a death toll of 14 people.

For most of us, cyclones are part of the news cycle – we see the wind-blown palm trees, eroded sea walls and flooded houses from afar on our TV screens each year. But to actually live through an extreme weather event like Evan is something else entirely.

“It was really scary – anyone would feel the same, especially when you’re living on a small island in the middle of the Pacific,” Silipa said.

“You feel really isolated and you don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow.”

For Silipa, Cyclone Evan was also what he describes as one of the worst times of his career.

Thrown in the deep end, with no experience, little training and having to navigate a cyclone, the likes of which hadn’t been seen in the country for over 20 years was a challenge to say the least.

Every summer people across the Pacific and in Australia’s northern states prepare themselves for cyclone season.

Some years pass and the worst that is seen is a bad storm, heavy rain and strong winds, but every now and then an event like Evan comes along.

It wasn’t the first major tropical cyclone to hit Samoa and it certainly won’t be the last.

Silipa was just one year old when Cyclone Val hit Samoa. He grew up with stories from his elders about the impact of the infamous cyclone.

“When people talk about cyclones in Samoa it’s the names Ofa and Val that the older generations reminisce about the most. I would often hear stories about how we tried to evacuate, how they carried us infants on their backs,” Silipa said.

On 7 December 1991 Cyclone Val made landfall in Samoa.

“It was a direct hit. It crossed over the big island of Savaii, made a loop and came back again. Because the eye of the storm was directly over Samoa it was the winds that had the most devastating impact.”

The cyclone lasted for five days and took the lives of 17 people.

Just 16 months earlier, Cyclone Ofa occurred off the coast of Samoa. In its case, it was the storm surge that had the greatest impact – the waves and swell causing destruction in coastal areas. Even carrying a ferry about a kilometre inland.

It was growing up in the aftermath of two of the most extreme weather events in living memory that prompted Silipa to pursue a career in the meteorological service.

“Growing up on a tropical island all year you expect a cyclone, but it makes you wonder why this is happening. We lose a lot after a cyclone hits, but I also found it exciting to try and understand how these natural phenomenon work.”

“It’s not often you hear kids here growing up saying ‘I want to be a meteorologist’, you hear lawyer, or engineer but I really saw a huge importance in the information provided by the met service in helping the community.”

United in the battle for a resilient future

The tropical climate of Samoa is worlds away from the wet and dreary climate of Northern Island that Dr Andrew Magee grew up in, and yet his fascination with the weather is as strong as Silipa’s.

“I’ve always been interested in the weather and how the natural world around us works,” Andrew said.

Completing a Geography degree at Queen’s University Belfast, Andrew was led to the University of Newcastle on an exchange program.

“It was a stark contrast to where I came from. Australia is the land of droughts and flooding rains. There are so many extremes and no two years are the same. My time here exposed me to that, and it was the potential to better understand what drives these changes and massive swings in extremes that influenced the direction of my research.”

Andrew experienced the aftermath of a tropical cyclone for the first time in 2016 when he was confronted by the devastation of cyclone Winston in Fiji.

Cyclone Winston damage in Tailevu, Fiji. (c) Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade via Wikimedia Commons

Cyclone Winston damage in Fiji. (c) Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission Belur Math, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Cyclone Winston damage in Fiji. (c) Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission Belur Math, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Impact of Cyclone Evan in Samoa

On top of the flattened trees and obvious physical destruction, he was struck by the impact on every facet of life.

“It impacts the whole country, from the farmer who grows the crops, to market vendors who sell the crops, to those working in the tourism industry. Food prices spike and food supply is often an issue,” Andrew said.

Tropical cyclones account for 76 per cent of disasters across the Southwest Pacific region, and since 1950, have claimed the lives of nearly 1,500 people and significantly impacted a further 3.1 million.

“They are the predominant natural disaster across the region and in terms of what we know about them there are just so many research questions left to answer,” Andrew said.

This fascination with tropical cyclones has led to years of research including time in several Pacific Island countries working alongside locals to better understand their perceptions of tropical cyclones and how they receive information to prepare for the upcoming season.

He discovered information passed down through generations, from the market vendor in Fiji who told him she predicts the upcoming season by the size of her mango crop, to the fisherman who can predict a cyclone might be coming by a decline in fish stocks or different bird species flying over his home.

Andrew’s research to date has culminated in the launch of a new tropical cyclone outlook that gives people across the Southwest Pacific months more to prepare for the cyclone season, hopefully providing a key to ensuring more effective disaster management.

Andrew’s research to date has culminated in the launch of a new tropical cyclone outlook that gives people across the Southwest Pacific months more to prepare for the cyclone season, hopefully providing a key to ensuring more effective disaster management.

“Tropical cyclones aren’t a new phenomenon, and they will continue to wreak havoc across the Southwest Pacific region, Australia and other cyclone-affected regions around the world,” Andrew said.

“And of course, it’s very easy for us to say – ‘you should be prepared all the time, you should have everything in place’. But in reality, life gets in the way.

“That’s why local meteorological services and tools for communicating with the community are really important. And it’s also why science and research play such an important role in informing what the upcoming season might look like both in the months ahead and in the days and hours before an event.”

“If we can just make small incremental steps in reducing disaster risk and informing the population of the risks associated with the coming cyclone season, then I believe it has the potential to save lives.”

Silipa agrees and it’s here in this world of extreme weather that Andrew’s research and the reality of daily life in the Pacific collide.

Assembling a Lifesaving Toolkit

The 2020/21 cyclone season (November – April) is already well underway and for Silipa that means an increase in monitoring, analysing the huge amount of weather data coming his way, translating it into easily understood language and making sure it gets to the people who need it most - women, men, children on the ground in towns and villages around the country.

A lot has changed at the met service in Samoa since 2012 and Cyclone Evan. Silipa said there were a lot of lessons learnt from that time, many improvements have been made and the met service now plays a much bigger role in helping people prepare for tropical cyclones.

This year they’ve added Andrew’s Long-Range Tropical Cyclone Outlook for the Southwest Pacific to their toolbox.

“We do have limited resources here, but we get help from people like Andrew Magee, his model backs up our existing information, it provides extra data, and the frequency of updates can really boost our confidence in the information we’re providing to our stakeholders. It’s hugely useful for the Pacific,” said Silipa.

“When cyclones are part of everyday life people do get complacent, we know that people pay attention when we put information out there about upcoming activity but there’s still more to do in terms of raising awareness and getting the community on board.”

Add to the mix the impact of climate change and the future outlook for tropical cyclones has people like Silipa on the edge of their seats.

Rising sea levels and subsequent changes to tropical cyclone related exposure and vulnerability will only amplify the impact of future tropical cyclones across the Southwest Pacific region. And while Andrew said that the jury is still out on exactly how climate change will impact future tropical cyclone activity, the science is telling us that we may see fewer but more intense tropical cyclones across the Southwest Pacific.

That could mean more cyclones like Evans and Val are on the cards.

“It certainly doesn’t leave any room for complacency,” Andrew said.

“We need to change the behaviour of people here and how we think and anticipate what climate change is going to do in a very isolated place in the middle of the Pacific Ocean,” Silipa said.

It also brings the importance of research like Andrew’s into sharp focus. Those few extra months to prepare for the upcoming season could mean the difference between complete devastation and loss of lives, or not.

This project is a joint collaboration between the Centre for Water, Climate and Land (CWCL) at the University of Newcastle and the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA).