You look at that idealised version of yourself and you just want it – you just want it to be real […] the more you do it, the better you get at it and the more subtle your editing is the easier it is to actually see yourself as that version.

Abigail was one of nearly 80 young people my colleagues and I interviewed as part of research into selfie-editing technologies. The findings, recently published in New Media & Society, are cause for alarm. They show selfie-editing technologies have significant impacts for young people’s body image and wellbeing.

Carefully curating an online image

Many young people carefully curate how they appear online. One reason for this is to negotiate the intense pressures of visibility in a digitally-networked world.

Selfie-editing technologies enable this careful curation.

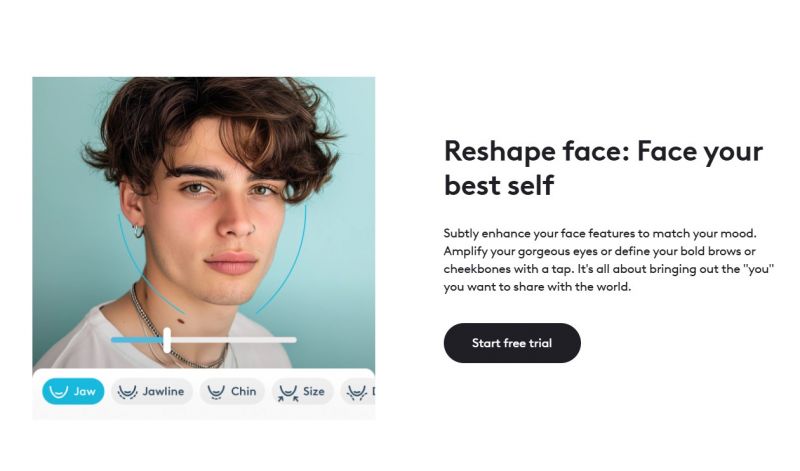

The most popular selfie-editing apps include Facetune, Faceapp, and Meitu. They offer in-phone editing tools from lighting, colour and photo adjustments to “touch ups” such as removing blemishes.

These apps also offer “structural” edits. These mimic cosmetic surgery procedures such as rhinoplasty (more commonly known as nose jobs) and facelifts. They also offer filters including an “ageing” filter, “gender swap” tool, and “make up” and hairstyle try-ons.

The range of editing options and incredible attention to details and correction of so-called “flaws” these apps offer encourage the user to forensically analyse their face and body, making a series of micro changes with the tap of a finger.

A wide range of editing practices

The research team I led included Amy Dobson (Curtin University), Akane Kanai (Monash University), Rosalind Gill (University of London) and Niamh White (Monash University). We wanted to understand how image-altering technologies were experienced by young people, and whether these tools impacted how they viewed themselves.

We conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with 33 young people aged between 18-24. We also ran 13 “selfie-editing” group workshops with 56 young people aged 18–24 who take selfies, and who use editing apps in Melbourne and Newcastle, Australia.

Most participants identified as either “female” or “cis woman” (56). There were 12 who identified as either “non-binary”, “genderfluid” or “questioning”, and 11 who identified as “male” or “cis man”. They identified as from a range of ethnic, racial and cultural backgrounds.

Facetune was the most widely-used facial-editing app. Participants also used Snapseed, Meitu, VSCO, Lightroom and the built-in beauty filters which are now standard in newer Apple or Samsung smartphones.

Editing practices varied from those who irregularly made only minor edits such as lighting and cropping, to those who regularly used beauty apps and altered their faces and bodies in forensic detail, mimicking cosmetic surgical interventions.

Approximately one third of participants described currently or previously making dramatic or “structural” edits through changing the dimensions of facial features. These edits included reshaping noses, cheeks, head size, shoulders or waist “cinching”.

Showcasing your ‘best self’

Young people told us that selfie taking and editing was an important way of showing “who they are” to the world.

As one participant told us, it’s a way of saying “I’m here, I exist”. But they also said the price of being online, and posting photos of themselves, meant they were aware of being seen alongside a set of images showing “perfect bodies and perfect lives”.

Participants told us they assume “everyone’s photos have been edited”. To keep up with this high standard, they needed to also be adept at editing photos to display their “best self” – aligning with gendered and racialised beauty ideals.

Photo-editing apps and filters were seen as a normal and expected way to achieve this. However, using these apps was described as a “slippery slope”, or a “Pandora’s box”, where “once you start editing it’s hard to stop”.

Young women in particular described feeling that the “baseline standard to just feel normal” feels higher than ever, and that appearance pressures are intensifying.

Many felt image-altering technologies such as beauty filters and editing apps are encouraging them to want to change their appearance “in real life” through cosmetic non-surgical procedures such as fillers and Botox.

As one participant, Amber (19), told us:

I feel like a lot of plastic surgeries are now one step further than a filter.

Another participant, Freya (20), described a direct link between editing photos and cosmetic enhancement procedures.

Ever since I started [editing my body in photos], I wanted to change it in real life […] That’s why I decided to start getting lip and cheek filler.

Altering the relationship between technology and the human experience

These findings suggest image-editing technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) filters and selfie-editing apps, have significant impacts for young people’s body image and wellbeing.

The rapid expansion of generative AI in “beauty cam” technologies in the cosmetic and beauty retail industries makes it imperative to study these impacts, as well as how young people experience these new technologies.

These cameras are able to visualise “before and after” on a user’s face with minute forensic detail.

These technologies, through their potential to alter relationship between technology and the human experience at the deepest level, may have devastating impacts on key youth mental health concerns such as body image.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

Related Articles

Giving men a common antidepressant could help tackle domestic violence: world-first study

In April 2024, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese declared domestic and family violence a “national crisis” calling for proactive responses that “focus on the perpetrators and focus on prevention”.The issue hasn’t really improved since then.

Read more

What is gingivitis? How do I know if I have it?

Do your gums look red and often bleed when you brush them, but they’re not painful? If so, you could have the gum disease gingivitis.

Read more

Not all processed foods are bad for you. Here’s what you can tell from reading the label

If you follow wellness content on social media or in the news, you’ve probably heard that processed food is not just unhealthy, but can cause serious harm.

Read more

Kids need to floss too, even their baby teeth. But how do you actually get them to do it?

A survey from the Australian Dental Association out this week shows about three in four children never floss their teeth, or have adults do it for them.

Read more

Pathway to purpose

From limited beginnings to limitless dreams - equity in education is giving Arthur Demetriou the chance to change the face of medicine.

Read more

“I thought I was a bad mother”: How telehealth changed a young boy’s life and gave a family hope

“I thought I was a bad mother,” says Marlie Matthews, tearfully. “I tried everything, but Marcus was getting more and more behind. He wasn’t speaking much and when he did, I couldn’t understand him. It was very hard on all of us.”

Read more