Growing up, Associate Professor Tamara Blakemore would spend hours listening to her family’s stories. Those stories existed as oral histories of times past, of tragedy and triumph, and as powerful lessons of what mattered and what made things work.

The fourth generation to live on the shores of Lake Macquarie in the NSW Hunter region, Tamara recognised her family’s experiences were deeply intertwined with the area and its resources.

“I became really interested in people and their stories – the ties that bind them and the ties that break,” Tamara reflects.

“The longer I practise, the deeper my appreciation is of the power of place in those stories.”

"The longer I practise, the deeper my appreciation is of the power of place in those stories."

Despite its revival, the Hunter region fares worse in terms of unemployment, youth unemployment and Year 12 completion rates in comparison to the rest of the country*.

Annual crime statistics continue to highlight the region's youth crime as prevalent and severe.

It’s easy to get lost in the data. But for the human service workers at the coalface, each of those numbers represents a person with a unique and complex story.

Tamara is one of the people who now sits at that coalface, and it’s those stories that form the heart of her practice.

After more than 25 years as a social worker, she has encountered hundreds, if not thousands, of stories.

The reason young people use violence is vast and complex, however as Tamara absorbed each and every individual’s experience, a pattern emerged.

“It quickly became clear to me that the young people using violence had often been victims of trauma themselves,” she says.

“In an overburdened justice system, the solution is too often one-size-fits-all. There hasn’t been consideration of the whole picture – someone’s background, their upbringing, their community. The full context.

“Until we can understand what has happened to a young person which led them to using violence, we can’t as service providers offer the meaningful and purposeful support they need.”

"...young people using violence had often been victims of trauma themselves."

Working closely with cross-disciplinary colleagues in the College of Human and Social Futures at the University of Newcastle, Tamara was determined to change the narrative. On her quest for a solution, it was a conversation with a local youth magistrate that sparked an idea.

“Magistrate Tracy Sheedy wanted to know why the young people before her on criminal matters were disengaged from the education system. So, we secured a small amount of funding and spoke with service practitioners in our region across 10 different sectors,” Tamara recalls.

“Interestingly, we heard that young people’s crime was about two things; connection – finding and forming identity, but also communication – hear me, see me, take notice of my needs.”

Hear me. Hear my story. It all leads back to stories and validating the experience of every individual.

“When you actually ask a young person about themselves, and you place them as the narrator, and as the expert in their own experience, their wisdom drives the work,” she continues.

“They’re far more likely to engage with change if they feel seen, heard and understood. This leads to increased connection – with the world and those around them – which is the other key factor identified as contributing to youth violence.

“We heard from practitioners that there was nothing available to support them to work in this way, so Triple N was born.”

Name.Narrate.Navigate, also known as Triple N or NNN, is a trauma-informed and culturally responsive program addressing youth violence. Its focus is 12 to 18-year-olds who have used or experienced violence, and the practitioners who support them.

The eight-week program harnesses ideas around validation, connection and communication by placing participants at the heart of its approach.

Informed by dialectical behaviour therapy and photovoice, small groups are encouraged to undertake activities to ‘name their emotions, narrate their experience, and navigate the complex circumstances in which violence, abuse and trauma occurs’.

“When you actually ask a young person about themselves, and you place them as the narrator, and as the expert in their own experience, their wisdom drives the work."

“When you can’t name how you’re feeling and how other people are feeling, it can be difficult to have self-awareness and it can be difficult to self-regulate. The activities allow participants to identify their emotions, and therefore name them, and then narrate their experience through that lens,” says Tamara.

“Essentially, we want to equip these young people with better communication, empathy and self-awareness skills, whilst also improving their self-regulation. Validating their personal stories encourages authentic connection.”

Harnessing Aboriginal ways of knowing and doing, the program is grounded in Country, acknowledging that place plays a key role in contextualising and healing people and their experiences.

“I think all our stories have roots, and we're all grounded in place in some way. All young people's context in terms of their community has real relevance in how they see the world, but also how they see themselves and what they see as possible for their futures,” explains Tamara.

Participant photo shows shadow crossing a bridge

Participant photo shows pair of thumbs breaking a twig

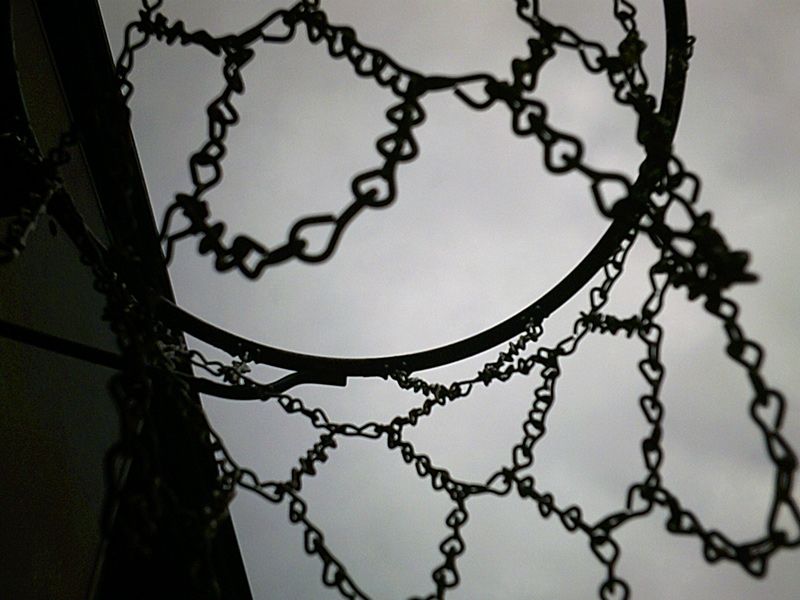

Participant photo shows chain basketball hoop silhouetted against gloomy sky

Participant photo shows two figures walking along concrete path - one throws a peace sign

Participant photo looking down at trousers and shoes

Leaving a regional community in New South Wales’ Northern Rivers, Aunty Elsie Randall had to abandon her roots as a young person to focus on survival.

“I came from a rural setting where family and connections and that kinship model really, really mattered,” explains the Bundjalung and Yaegl woman.

“But my family and my connections were really broken down and I didn’t feel safe.

“I didn't tell anyone what I was experiencing because I didn't think anybody else going through the same thing, so I carried it alone.”

Fuelling her 35 years in human services, Aunty Elsie’s own journey has motivated her support of other young people who have experienced trauma.

“I didn't tell anyone what I was experiencing because I didn't think anybody else going through the same thing, so I carried it alone.”

Working alongside Tamara Blakemore as Triple N’s Cultural Practice Lead, she strives to make participants, in particular young women, feel seen and validated in a way she wasn’t.

“What I love about the groups is that it takes out the individual and telling our stories in isolation – it's about sharing. It's also about putting these women in a room together, where they're not alone,” Elsie says.

“We see a huge shift in behaviour – it’s so much more than verbal. It’s the way they conduct themselves, the way that they use their tone and their body language. And what it tells us is that they feel safe in being vulnerable.”

Echoing Elsie’s passion, Triple N Program Manager Louise Rak has been co-facilitating sessions with Aunty Elsie for four years and revels in their work.

“The energy, it's awesome. We aim to foster this sense of trust, stability, and the elements young women need growing up anyway, but those who have gone through trauma and neglect often don't have that experience,” Louise explains.

“So, we've got a real obligation and duty to create that space with each other. And Elsie just does that just by breathing. It’s so natural.”

A researcher specialising in young women’s experiences with violence, Louise’s work with Elsie led them back to Bundjalung Country in the NSW Clarence Valley, where Louise has been welcomed by the Elders to deliver the program alongside Elsie.

“As a result of centuries of colonisation, dispossession, and subsequential trauma, there is still an over representation of Aboriginal people in the justice system, and we see the same thing in our work,” Louise says.

“80 per cent of our young women coming through the program identify as Aboriginal and we see many of them keen to strengthen their connection to their culture and country.”

“Without even really knowing, they're searching for their kinship model. They're searching for their sense of belonging,” Aunty Elsie adds.

Encouraging that connection is a primary purpose of Triple N. As an accomplished artist, Aunty Elsie’s skills lend themselves well to the creative mythologies at the heart of the program.

“We do a lot of work with creative storytelling, which we can trace back many, many moons. Photo taking and art are a great way to encourage sharing and healing,” she says.

“They’re a way to convey who you are, where you come from, all the cultural values and belief systems and all those beautiful features who make us, us. We can take that emotional content and not worry about having another person in front of us, assessing us.

“Because when you talk to a piece of canvas, there's no judgement. It's all about you telling the story.”

Aunty Elsie picks up a pen. She begins making marks on paper, expertly turned a series of unassuming circles into an intricate story of connection and kinship which she narrates as she draws.

Beside her sits 16-year-old Jasmine** who watches closely, absorbing both the story and her techniques.

Jasmine is one of the many young people who have been through the program since its inception five years ago.

At just 13, Jasmine found herself tangled in the justice system and unable to see a way out. She reflects that her attempts to find a community meant she ‘grew up too fast’.

"...when you talk to a piece of canvas, there's no judgement. It's all about you telling the story."

“I went down a bad track at school and fell in with friends in the wrong crowd,” she explains.

“Back in the day I was always like ‘I’ve got to slow down; I need to start being a child better', but I was always with older kids, and I got into trouble.”

Now a graduate of the program, the Birpai and Worimi woman is proud to share her successes.

“Since doing it [Triple N], I haven't been in trouble with the police. It's been good. Not having to worry about appointments and just focus on work. Getting life on track. Getting to places,” she says.

“I had a name for myself but it's slowly getting erased. I've got a new name coming in and better things on the way. I'm doing things other girls my age won't be able to do until they're much older, so in a way my trauma actually got me somewhere positive.”

Forming a strong bond with the team, Jasmine has remained connected to the program with a unique purpose. Part of the feedback loop integral to Triple N’s success, she helps ensure the content remains relevant for her peers.

“It's good to work with people who understand what you've been through and how to treat you, so you don’t go down that path again. Who have come from, not the same, but similar, stories and backgrounds,” she explains.

Aunty Elsie draws with NNN graduate Jasmine

Triple N session

And it’s this understanding that led to the natural evolution of Triple N.

Now boasting an accomplished portfolio far beyond the initial intervention program for young people, the team has trained more than 1000 practitioners to be able to deliver the program themselves across a range of contexts and locations throughout NSW.

Add to that a suite of educational resources ready for commercialisation and a huge body of research and evaluation, it’s a success story that remains true to its roots.

“I had a name for myself but it's slowly getting erased. I've got a new name coming in and better things on the way."

Despite the expanding scope of work, the heart and soul of Triple N always comes back to people and their stories.

“I'm still on my healing journey. I just cope better. But it's how we pass on those mechanisms to a younger generation, give them the resources to cope and get through life, that makes a difference,” says Aunty Elsie.

“This program is making that difference.”

*Blakemore, T., McCarthy, S., Rak, L., McGregor, J., Stuart, G., & Krogh, C. (2021). Postcards from practice: Initial learnings from Name.Narrate.Navigate.

**not her real name