Well, that’s certainly the hope, after researchers from the University of Newcastle and Hudson Institute of Medical Research made a discovery that is set to literally rewrite biology textbooks.

In a world-first analysis of testicular fluid, it has been discovered that – contrary to years of accepted knowledge – proteins found only in sperm can, in fact, enter the bloodstream.

It had long been assumed that these sperm-specific proteins were restricted within the sperm-producing tubules. However, this new research shows that some proteins enter circulation, with researchers hypothesising it is the body’s way of building a tolerance to what may otherwise be seen as a foreign body within the system.

So why is sperm circulating through the body such an exciting breakthrough? Early work suggests there are potentially two major benefits: one life-giving, the other life-saving.

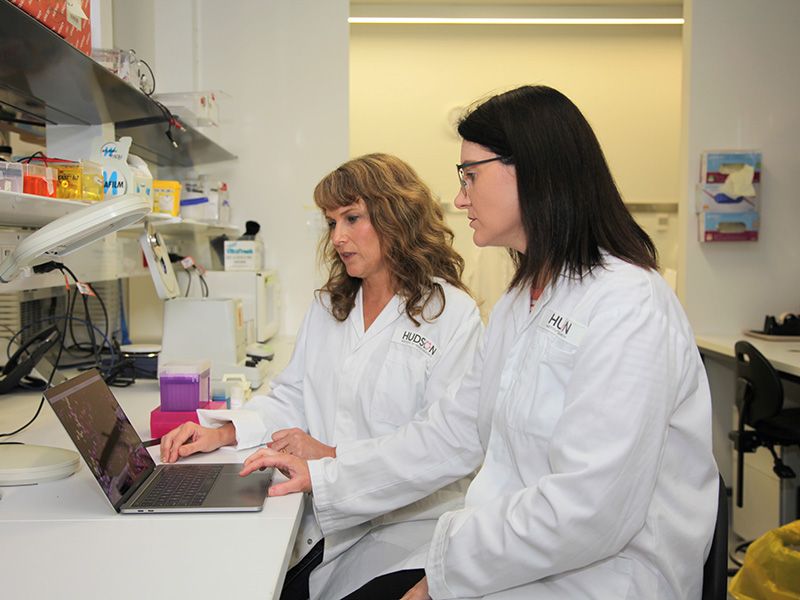

Dr Liza O'Donnell in the lab

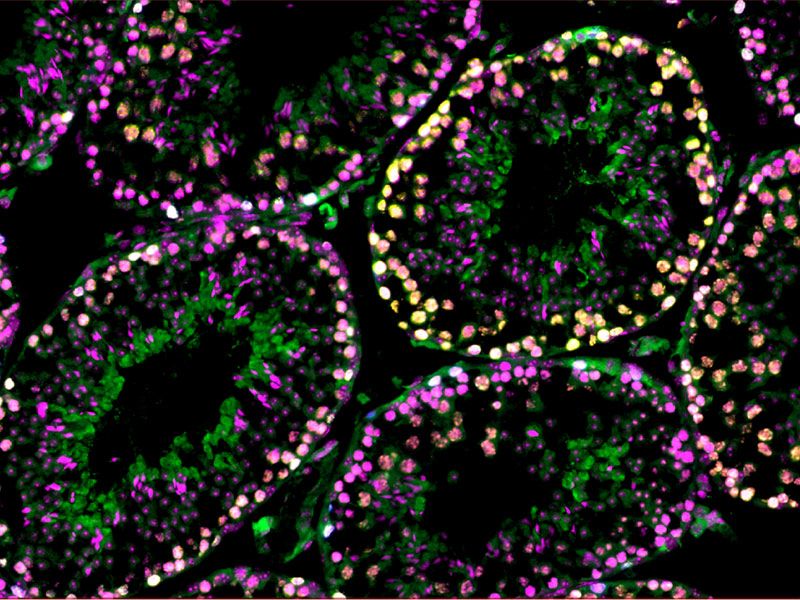

Image of testis on a laptop

Dr Liza O'Donnell (L) and Dr Penny Whiley in the lab

Testis under the microscope (Photo: Penny Whiley, Centre for Reproductive Health, Hudson Institute of Medical Research)

First – and perhaps most obvious since sperm is one of the critical ingredients in creating life – this discovery could lead to huge changes in the treatment of male infertility.

According to a 2017 article in Australian Family Physician, 15 to 20 per cent of couples are affected by infertility, with male issues contributing in 50 per cent of cases.

What’s more, research shows sperm counts fell a whopping 60 per cent in Western men between 1973 and 2011, with Professor Shanna H. Swan from the Mount Sinai School of Medicine pointing the finger at chemicals called endocrine disruptors that are increasingly common in modern life as the culprits.

"Endocrine disruptors have the ability to interfere with our reproductive systems," Professor Swan told the ABC, because "they interfere with the action of our natural hormones."

Basically, male infertility is common and looks set to become even more so in the coming years, which is likely to see an increase in the uptake of modern fertility methods – such as IVF – that require the harvesting of sperm.

Many men can give a sperm sample the traditional way – in a cup. But what if you don’t have any swimmers making their way out into the big, wide world? Then you may need to have your sperm harvested in other ways.

(Gents, you may want to cross your legs before proceeding.)

While there are a variety of procedures available to harvest sperm, none are particularly gentle on an area that is packed full of sensory nerve endings (it’s a trade off – the reason things can feel so good down there is also the reason why an accidental knock can see a grown man reduced to a blubbering mess).

One of the more common methods for retrieving sperm is to stick a needle into a testis to remove tissue, although it’s not uncommon to require an incision be made to remove a larger tissue portion.

These procedures are performed under either local or general anaesthetic, but the next 24 to 48 hours are still spent in a state of, shall we say, discomfort – some men experience nausea, vomiting and are even admitted to hospital overnight.

However, for some 50 per cent of prospective parents, the real pain comes when the results are delivered.

“The surgery is unsuccessful in up to half of all patients for various reasons,” co-lead author Dr Liza O’Donnell says.

So you undergo an invasive, painful process and in the end, it has a coin-toss’s chance of being successful.

While the discovery of sperm particles entering circulation doesn’t necessarily mean this success rate will improve, the hope instead is that a far less intrusive treatment can be developed to successfully test for fertility.

"The surgery is unsuccessful in up to half of all patients."

“We found that the levels of some of the sperm-specific proteins in the testes fluid reflected the level of sperm production within the tubules, suggesting these proteins could be an indicator of fertility status in men,” Dr O’Donnell says.

“Now that we know many sperm-specific proteins are able to be released from the testes, there’s potential to predict success by a less-invasive blood test.”

So perhaps a finger prick, rather than using a scalpel to remove a literal slice of testicle? That’s a no-brainer.

(Gentlemen, as you were.)

Let's talk testes

From the cute to the crass – and from the ages of 3 to 13, it tends to go from one extreme to the other – there are no shortages of names, nicknames and misnomers for the various parts of the male genitals.

So let’s get a few of the basics straight, using academic nomenclature:

Testis: The organ that produces sperm, also known as the testicle.

Testes: Plural of testis.

Tubules: In this context, the seminiferous tubules within the testes where sperm is created.

As for the second huge boon this research could bring about, it could redefine the way certain kinds of cancer are being treated.

“Many of the sperm-specific proteins we found in the testes fluid are also known as cancer-testis antigens, or CTAs, which are often produced by cancers,” Dr O’Donnell says.

“CTAs are normally only produced by sperm in healthy men, but scientists have long believed that sperm-specific CTAs can’t enter the bloodstream.”

As to what the link is between this horrid disease and CTAs, the short answer is that cancer creates a variety of different proteins so as to have the best chance of surviving and migrating, and CTAs are very good at helping cancers to develop (because they are very good at helping sperm to function, and sperm – like cancer – are pretty tricky things).

Based on our prior understanding, certain CTAs were understood to only be found in either the male tubules, or in the broader systems of people who had cancer.

This meant that CTAs found in the broader system were thought to be a biomarker of cancer – if they can’t escape the tubules, why else would they be in a healthy man’s circulation?

But now, searching for CTAs as cancer biomarkers is going to require a rethink.

"Scientists have long believed that sperm-specific CTAs can’t enter the bloodstream."

What’s more, these CTAs are considered a great target in the development of immunotherapy, which is a form of treatment that sees the body – rather than, say, radiation or chemotherapy – battle cancer by generating an immune response.

Given the understanding that CTAs would only be found outside the tubules in people who have cancer, they have been trialled for use in immunotherapy by giving the body something to target and develop an immune response – essentially, the body would recognise that they don’t belong and attack.

However, being that they are common outside the tubules, these CTAs are likely to be far less effective as a target in immunotherapy, as the body has likely developed the aforementioned tolerance to their presence.

In short, if CTAs have been in the body the whole time, you can’t exactly turn around and try to convince the immune system that they are foreign intruders.

As a result, there will be some CTA-based immunotherapy approaches that may need to go back to the drawing board with regards to developing treatments for certain types of cancer.

This discovery may come across as a kick in the proverbials, but hey, far better to be aware of the issue and reassess, than to continue banging our heads against a brick wall.