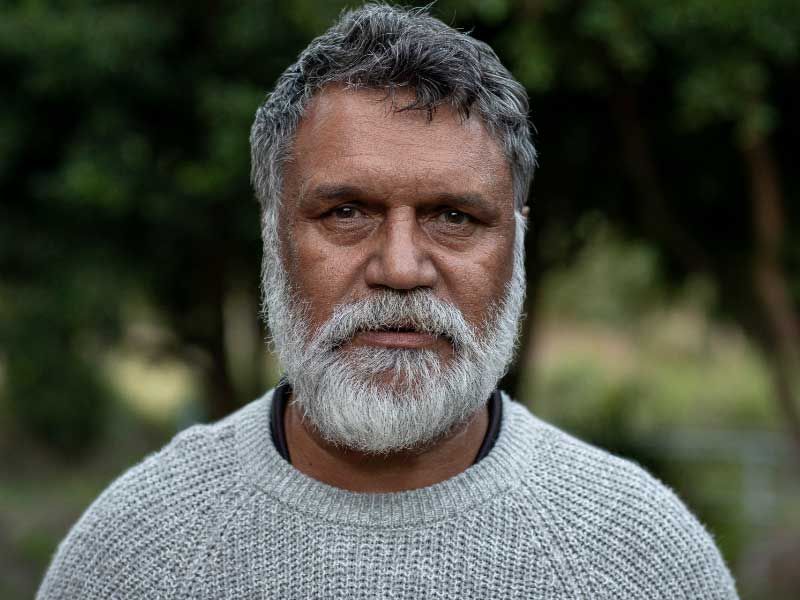

When Dr Ray Kelly was growing up in a mission on the outskirts of Armidale, NSW, he was surrounded by the languages of his family – Dhangatti and Gumbayngirr. A curious child, he enjoyed sitting around the fire listening to his grandparents tell stories. The sound and meaning of words intrigued him.

Years later, Ray continued to hear from others stories of his grandparents and their languages. He learnt that when his grandfather was once asked the word for telephone, he responded with “Muuya barrigi”. Flying breath.

Reviving Indigenous Languages

Decades later and now a leading Indigenous languages researcher and Deputy Head of the University of Newcastle’s Wollotuka Institute, Ray didn’t need to look too far when searching for a name for his innovative multi-media language program. Muuya Barrigi was launched in 2020 and draws heavily on Ray’s language skills and understanding, offering participants insights and practical application skills for pronunciation as well as word and sentence structure. Participants don’t have to have any previous language experience, but Ray says “they all want to reclaim a sense of identity”.

For Jimmy Kyle, a Dhangatti man a long way from home during Melbourne’s extended lockdown, the classes were about connecting to community and culture. “Uncle Ray’s approach is so much more than how to pronounce a word although that is part of it,” he says. “It was a brilliant exercise for your mind and it was hands down one of the best things I’ve done to serve my soul.”

COVID-19 forced Muuya Barrigi online and it was delivered over 12 weeks to a core group of students and community members, the majority of whom were Indigenous. Participants logged on throughout Australia – from Melbourne to Kempsey – for weekly classes via zoom. The program enabled participants to learn in a safe, non-judgemental environment.

The language classes helped Jimmy gain a deeper understanding of the ‘kriol’ he spoke and other traditional words he heard around him growing up at Billybyang Creek, inland from Kempsey. “You can hear elements of the way old people thought in the words we use,” he says. “You get a greater understanding of the history through language. I’ve found I’ve been able to see the connections between different Aboriginal languages and it has also helped me with my English.”

Dr Ray Kelly with students around a campfire

Dr Ray Kelly with students at the Wollotuka Institute

Dr Ray Kelly

Ray Kelly’s passion for language developed over time. “I would have liked to have been involved (more formally) earlier,” he says, “but maybe it was always going to take time for me to gain a deeper understanding of the impact it has on healing and connecting our people.”

The three particular Aboriginal languages of Ray’s childhood were at the heart of his PhD thesis at the University of Newcastle: Nganyiwan (or Unniwan), Gumbayngirr and Dhangatti. It wasn’t uncommon for dialects to evolve when people from different communities were forced on to missions.

There were more than 250 indigenous languages across Australia at the time of European settlement in 1788, compared with about 120 spoken today, according to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. The 2018 Census showed that only 13 traditional languages are spoken by Indigenous children and this is mainly in Western Australia and Northern Territory. In NSW, about 1800 people speak Indigenous languages.

Ray’s life story reflects the experiences of many Indigenous Australians. He felt alienated from his culture as a school student. “In high school in the ’70s what they were telling me didn’t make sense (about the history of Aboriginal people),” remembers the 60-year-old. “I rebelled against it. It wasn’t right.

“The ‘deficit model’ that had defined the narrative about Indigenous Australians wasn’t something I could relate to and we are still trying to resist it, even when it comes to our languages. I was being taught that we are part of a dying culture and people still believe that. The narrative about our citizenship and nationhood is dominated by this lie.”

Why does language matter? “Language is at the centre of who you are, your sense of belonging, your sense of place,” says Ray. “We’re (Indigenous Australians) forced to find our sense of identity in a vacuum. Many Indigenous people experience profound shame about their culture, and in particular their language. “From my own experience I know that that modern linguistics failed to reach deeper into the social and cultural knowledges that still existed within communities during the 1960s, ’70s and ‘80s.”

According to Ray, the single greatest threat to the reinstatement of everyday language use amongst his people “will be the failure to find common ground between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in recognising our priceless intellectual sovereignty and the power that is has to heal the deep wounds from the past.

“Preserving traditional languages is about enquiry, critical thinking, and intellectual freedom. These are the qualities that have underpinned our languages for thousands of years and we have to hold on to that.”

University of Newcastle associate lecturer James Ballangarry, a Gumbayngirr man from Bowraville, has turned to Uncle Ray for mentorship in regard to his own language learning. As an undergraduate student with the Wollotuka Institute where he now teaches, he sought out Ray’s “wisdom and guidance”. “He encourages unique thinking and he supports the growth of culture.”

James also participated in the online Muuya Barrigi program. “Uncle Ray doesn’t teach from a ‘deficit perspective’. He shows us that language is alive around us.”

Ray is now focused on how to make the language program accessible more widely. “My dream would be to have an Indigenous-led linguistics recovery program across Australia.”

It is a dream Jimmy Kyle supports. “If only we could clone Uncle Ray,” he says with a laugh. “Seriously though, when can we start (the program) again? I’m keen.”