University news

Menu

Indigenous history grounds new Australians

When Tenzin Legden welcomes refugees to Australia, one of the first things he does is run through an orientation to familiarise them with their new home.

They cover key things like how to open a bank account, to dial ‘000’ in an emergency and – most importantly to Tenzin – an in-depth history of the traditional owners of the land.

For Tenzin, it’s a ritual of great significance, as it’s one he and his parents went through themselves when they first arrived from India in 2014.

Born in refuge to Tibetan parents in the state of Himachal Pradesh, Northern India, culture and identity remain complicated topics for he and his family.

At an age when his Aussie peers were preoccupied with learning to drive, Tenzin was leaving a simple life in a Buddhist boarding school of 10,000 students for Sydney’s glittering Northern Beaches. The stark shift would be overwhelming for most, but for Tenzin, it was the moment he felt he’d found home.

“My grandparents and then my father fled the Chinese occupation in Tibet. As Buddhists, they were unable to practice their culture, religion or speak their own language in fear of the regime. People feared arrest – or worse – just for walking down the street with an image of The Dalai Lama on their person,” he reflects.

“I went to a school in India with many children whose parents had been political prisoners or killed for their beliefs. I know my father went through some dark experiences, but we don’t tend to talk about it. We look forward.”

Despite having been born in India, Tenzin’s parents’ refugee status meant he and his family would never be acknowledged as citizens, and subsequently never entitled to any kind of support or social security.

“We were essentially unrecognised in India.

“My parents wanted a better life for us, so we left just after I started high school. Although we had no family or friends in Australia, they knew we’d have access to the kind of opportunity we’d never had before.

“It was the first time we could belong to a country,” he explains.

But with new opportunity came a whole new challenge.

“When I arrived in Australia there was suddenly this overwhelming freedom to do anything, but also a pressure to ‘have a dream’. I didn’t have a dream. All I wanted was to provide for my parents and make sense of our story.”

Having limited knowledge of his family history in Tibet, Tenzin became consumed by a search for some ‘connection to place’, which and eventually led him to Deep Time – an unconventional cultural digitisation project that would deliver the connection to culture he so badly yearned for.

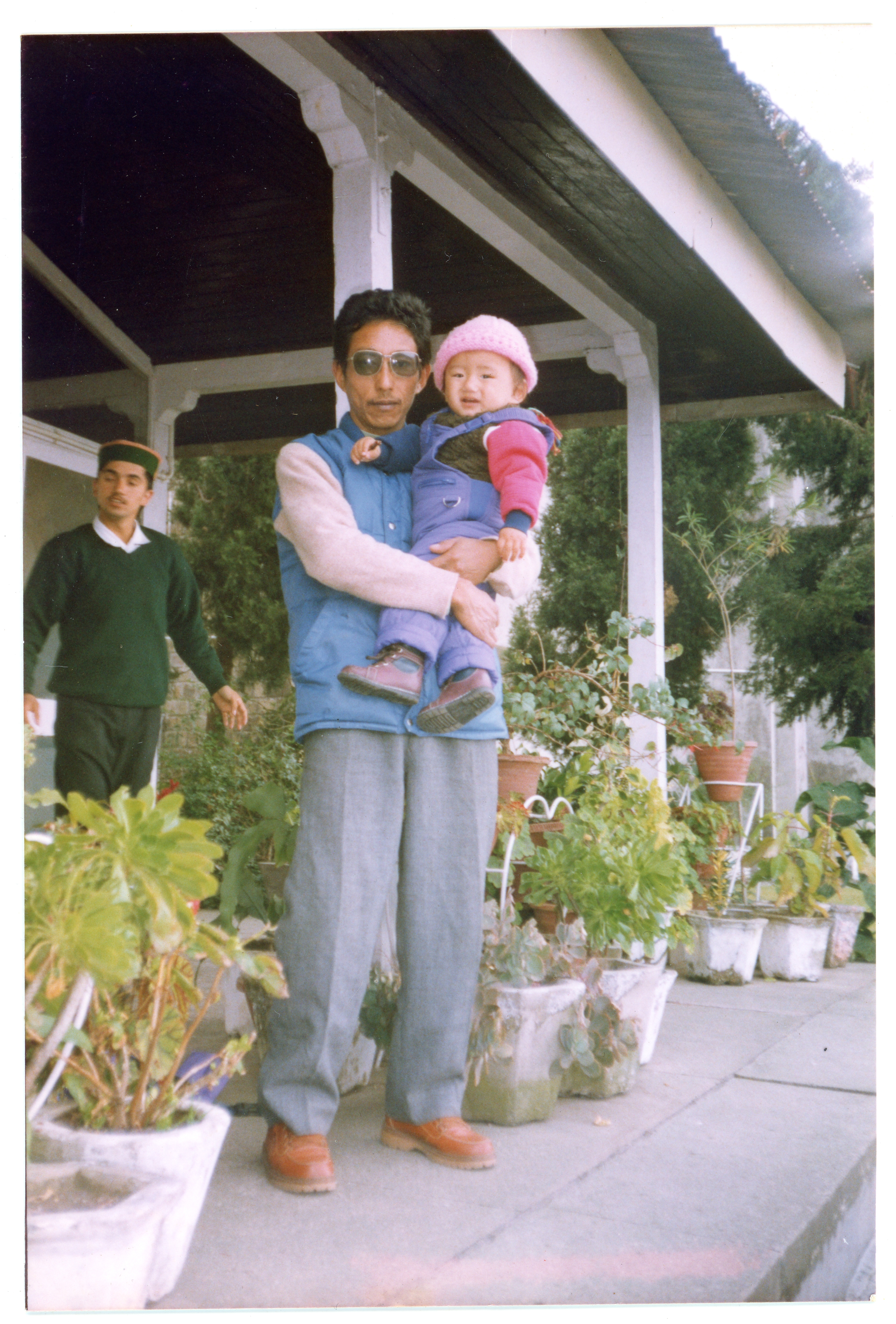

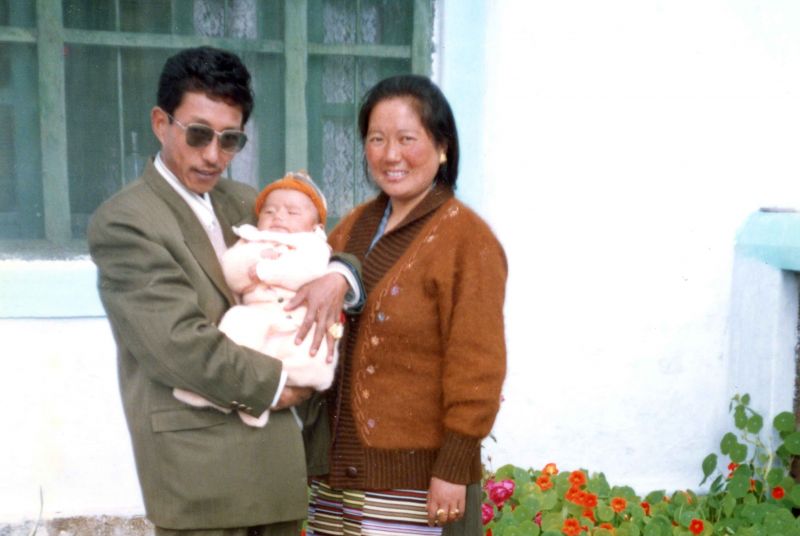

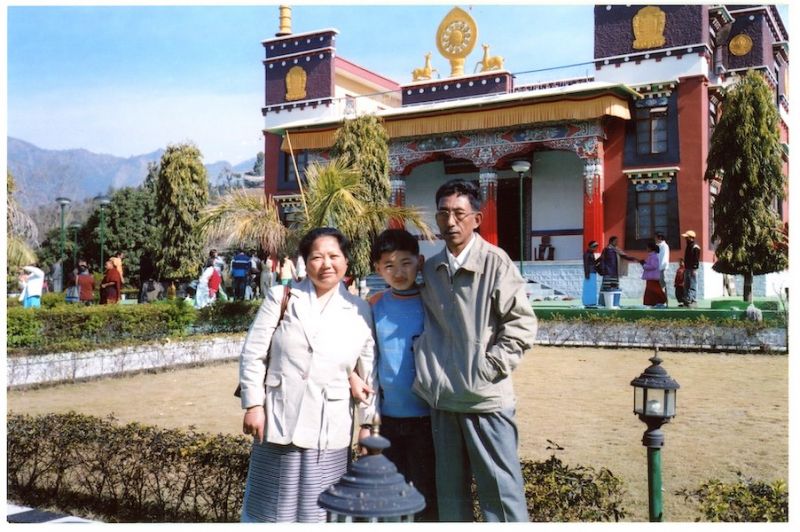

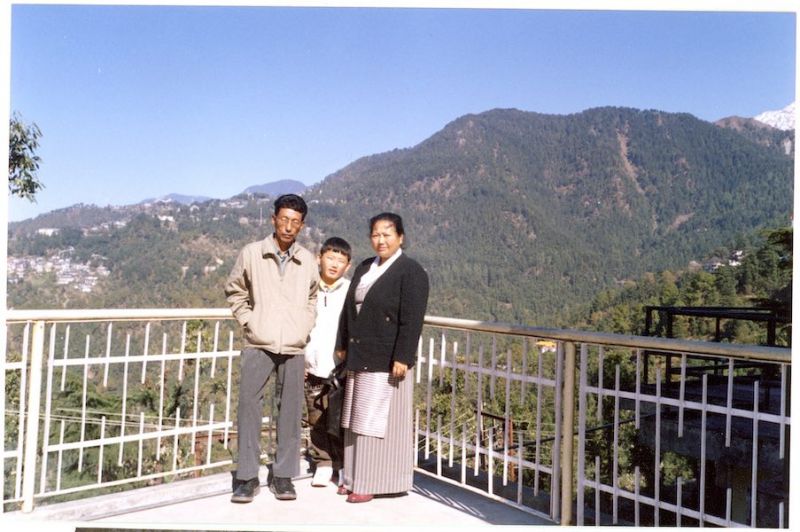

Tenzin and his parents in Dharamsala, state of Himachal Pradesh in India

Tenzin and his parents in Himachal Pradesh in India

Tenzin and his parents in Himachal Pradesh, Northern India

A unique fusion of ancient civilisation and modern technology, Deep Time is a virtual glimpse into the world’s oldest surviving culture – Aboriginal Australia.

In 2010, more than five thousand Indigenous artefacts were uncovered when works to build ‘the largest KFC in Australia’ were undertaken in Newcastle CBD. The construction unearthed tools which revealed the area was a significant 6,500-year-old work site for Aboriginal people.

“When my family came to Australia, we had a brief orientation about Aboriginal culture and how the first nations people lived here, but the extent of their history didn’t hit me until I saw artefacts for myself,” Tenzin remembers.

After some soul searching, Tenzin began pursuing studies in psychology and philosophy in the hopes of learning more about the rationale behind human behaviour.

His interest in displacement led him to a work-integrated learning opportunity in the University of Newcastle’s GLAMx lab, where a team were working to bring the uncovered Indigenous artefacts off the shelves of the library’s archives and into the 21st Century. With the permission of Traditional owner groups, each piece was being painstakingly documented and some digitised using 3D scanning technology to develop a virtual reality re-creation of the original archaeological site. One that could stand the test of time in preserving Indigenous culture and ensuring its rich history would never be omitted from Australia’s story.

With the permission of Traditional owner groups, each piece was being painstakingly documented and some digitised using 3D scanning technology to develop a virtual reality re-creation of the original archaeological site. One that could stand the test of time in preserving Indigenous culture and ensuring its rich history would never be omitted from Australia’s story.

By placing a virtual reality headset on, the user is transported two metres underground to the dig site where they can use hand controls to inspect and learn about the use of the individual objects suspended amongst grid-like layers. Great care was taken to ensure authenticity by ‘placing’ each piece in the exact location it was found on site.

“The artefacts I was working with were six and a half thousand years old. For someone searching for rationale behind place and belonging, it [the project] had a big impact on me. It symbolised that something happened here. Something had been happening here long before English history books on Australia were written,” Tenzin explains.

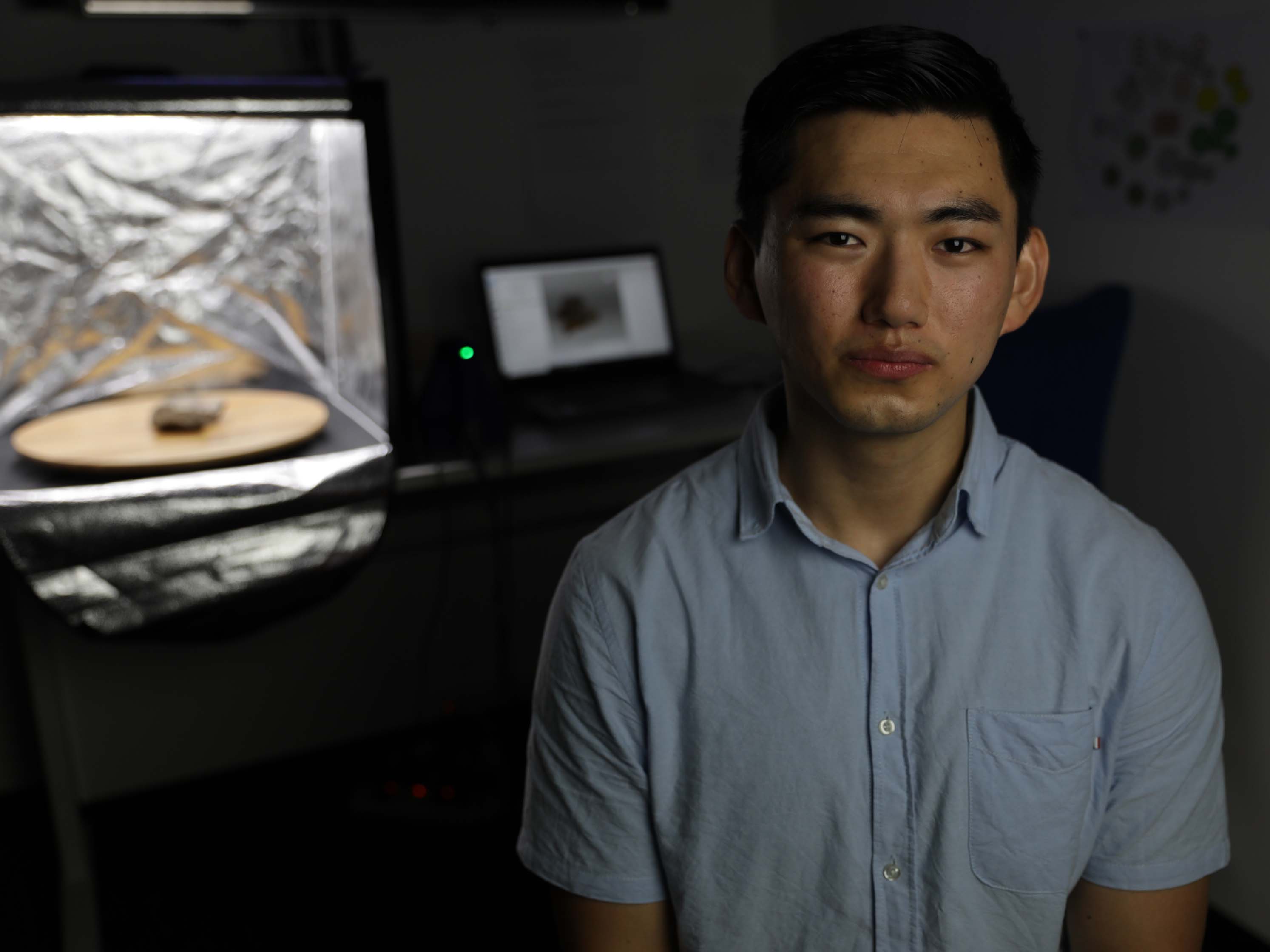

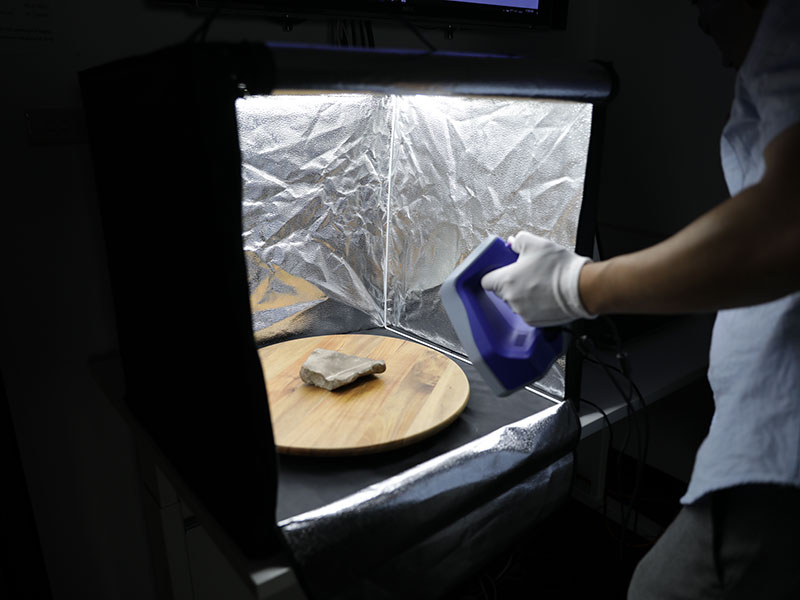

Tenzin works on ancient artefacts

Tenzin scanning artefact

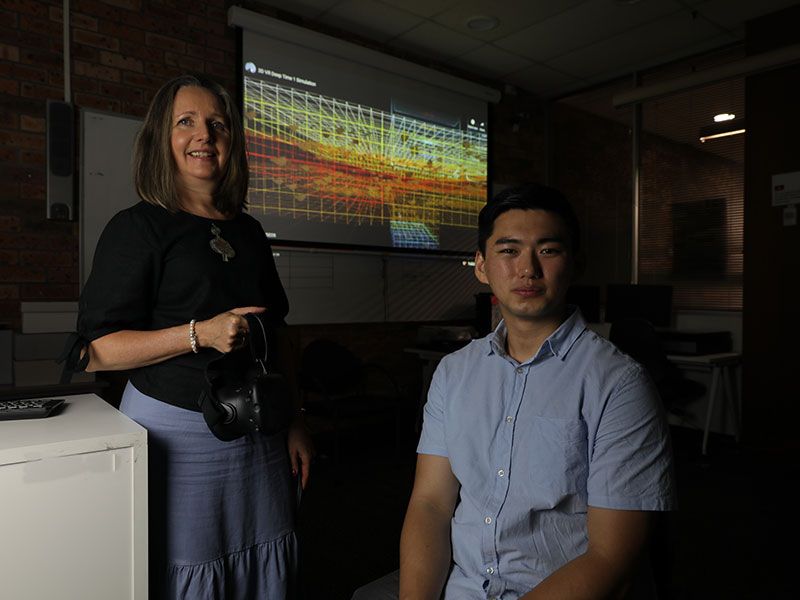

Digitisation Projects Coordinator Dr Ann Hardy and Tenzin

Tenzin with VR goggles

An urge to further his cultural capability saw Tenzin dig deeper and deeper into human history.

“I observed lectures at places like the Wollotuka Institute and researched to learn more and more about culture and displacement. Not only about Indigenous Australians, but also stories of others who had had their homes taken, including refugees.”

Driven to ensure the stories of the past continue to be relevant, Tenzin worked closely with the GLAMx lab throughout his degree on other digitisation projects. Now, it’s rare to find him without his trusty Nikon in-hand as he documents the simple moments in his daily life.

Reflecting on his journey – both physically and academically – he places great importance on reinvigorating history.

“I think digitising history is so important because lots of things aren’t in the history books. You get the perspective of the person or people writing and not a wholistic picture. Being able to preserve historical assets gives real context to the story.”

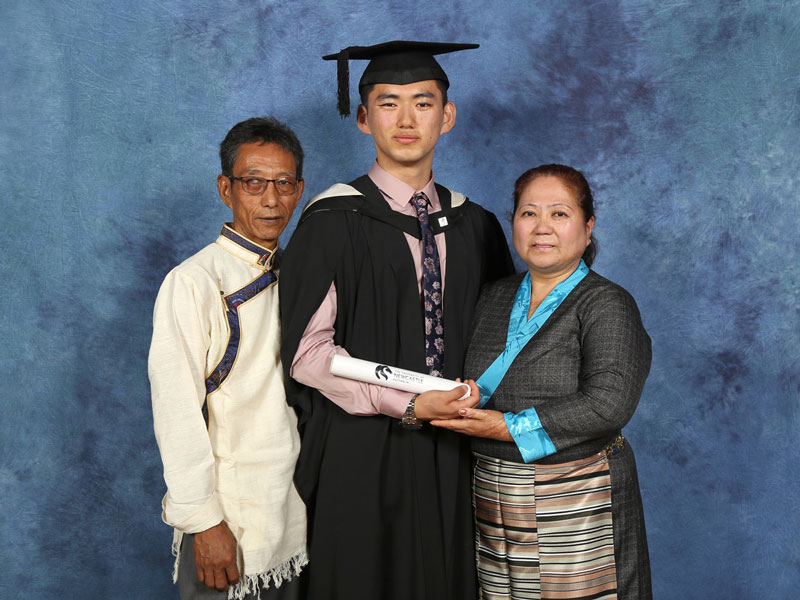

Six years on from arriving in Australia – Tenzin is 23, a university graduate and officially an Australian citizen. Yet he still remembers the first case worker who helped his family find a house and establish a new life in Australia.

Now he has the chance to play that same role for others.

Coming full circle to work with the settlement service who supported him, Tenzin is now delivering the same important orientation he once received.

“I love sharing this country’s rich history with new arrivals,” he smiles.

“I think working on the Deep Time project gave me a sense of duty here. I can’t preserve my own culture back in Tibet, but I can play a role in telling the story of who my new home belongs to. Really belongs to.”

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.