Tsunami threat to Sydney intensifies need for increased awareness

Whirlpools at the Spit, inundation of Manly Corso and major disruptions are possible impacts revealed in a first-of-its-kind study into the tsunami threat to all of Sydney Harbour.

Published in Scientific Reports and supported by the NSW Office of Emergency Management, coastal researchers from the University of Newcastle and the Bureau of Meteorology have modelled the effects of tsunami inundation in Sydney, forecasting the impact of events ranging in severity.

The results showed the potential for significant changes in the water, from powerful currents to the formation of dangerous whirlpools, highlighting the need for increased community awareness.

Lead author and PhD candidate, Kaya Wilson, said the tsunami risk to Australia was under-researched and needed to be taken seriously.

“When you broach the idea of Australia being susceptible to tsunami, you’re usually met with a dichotomy – either total disbelief that we’re at any risk, or panic as to what the threat means to the individual,” Mr Wilson said.

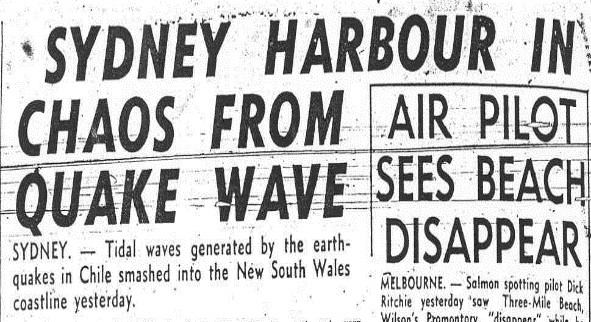

“NSW has been affected by serious events in the past – for example the Chile earthquake in May 1960, which caused major disruption to Sydney Harbour – and we need to ensure we’re equipped to best respond to all possible future scenarios.”

Hobart Mercury, 25 May 1960

What a tsunami might look like in NSW

The main cause of tsunamis is submarine earthquakes. The vast majority of these occur at ‘subduction zone’ tectonic plate boundaries, where two tectonic plates are colliding. When enough tension builds up, it is released and the force pushes the water column upward, causing waves to radiate outward.

For the east coast of Australia, one of the nearest subduction zones is the Puysegur Trench south of New Zealand. Because tsunamis can travel as fast as jet liners in the deep ocean, a tsunami originating from the Puysegur Trench could reach Sydney in about two hours.

Project lead and coastal geoscientist, Dr Hannah Power, said when considering a likely scenario for Sydney and other estuarine areas on the east coast, our understanding of tsunami needed to be accurate.

Dr Hannah Power, project lead

“A Sydney-sider will probably experience a tsunami in their lifetime, but the way we think about tsunami needs to be reframed to reflect a realistic picture of a likely event,” Dr Power said.

“Hollywood sells us images of huge walls of water and engulfing waves, but in fact we’d be looking at something more like a significant and unpredictable tide moving in and out in minutes rather than hours. The water could be rapidly rising and falling, with current speeds changing direction every few minutes. As a result, we could see dangerous whirlpools to the east of Spit Bridge, something which is reported to have happened in 1960 during the Chilean tsunami. We could also see serious coastal erosion impacting infrastructure.

“Some of the larger events we’ve modelled could cause rapid current speeds of up to eight metres per second, becoming dangerous very quickly. For context, an Olympic swimmer might swim two metres per second at their fastest.

“Although we wouldn’t expect a risk to the CBD, strong currents and unpredictable rapid water movements would make the harbour an unsafe place to be, posing a threat to swimmers, fishers, boaters and potentially those near the water.”

Dr Power stressed the importance of raising community awareness of the tsunami risk to Sydney to ensure better understanding of how to respond.

“If you think about a two metre swell, we wouldn’t feel the need for concern, however a two metre tsunami would be devastating,” Dr Power said.

“We need to put the risk in context for the general public, so that when we receive alerts warning of a potential tsunami threat, people take it seriously and act safely. That means following the instructions and warnings from our emergency services as advised, rather than trying to witness the event.”

Modelling the possibilities

The likelihood of a major tsunami impacting NSW is very low but the consequences of a tsunami can be devastating, as witnessed across the Indian Ocean in 2004, Japan in 2011 and the recent event in Indonesia.

The research team worked to model different scenarios from various source zones – locations where a tsunami could originate – at a range of earthquake magnitudes from a 7.5 up to 9.

Utilising an impressive seamless 3D map of the land and ocean floor around Sydney Harbour, which Mr Wilson developed by stitching together individual pieces of mapping information, the team were able to accurately replicate the effect of such events in Sydney.

Mr Kaya Wilson, lead author

“We looked at various likely scenarios ranging from a more likely 1 in 20-year event, to a more major 1 in 5000-year event,” Mr Wilson said.

“For example, the 1960 tsunami that came from Chile, had significant marine impacts in Sydney. We could expect a tsunami of a similar size in the Harbour once every 50 to 100 years.”

Dr Power emphasised the use of probability as a measurement should be put into context.

“When we say something has a 1 in 20-year likelihood, that doesn’t mean it happens once every 20 years. It means that, on average, there is a 1 in 20 chance of that event happening every year,” Dr Power said.

“Whilst you might think a 1 in 100-year event is infrequent and unlikely to happen in your lifetime, in reality there’s a 1 in 100, or a one per cent, chance of it occurring every single year.

“If you translate that to something people might put more emphasis on, perhaps like their health, if there was a one per cent risk of a medical procedure going horribly wrong, you might rethink whether you wanted to have that operation, which is why it’s imperative we have this research to support Australia’s emergency preparedness.”

Impact on emergency response

If a tsunamigenic event were to occur, warnings on the tsunami threat to the Australian mainland and offshore territories are provided to emergency services, the public and the media by the Joint Australian Tsunami Warning Centre. This centre is jointly run by the Bureau of Meteorology and Geoscience Australia. In NSW, the State Emergency Service coordinates the emergency response.

Mr Wilson explained that their research outcomes showing tsunami propagation in estuaries is useful for evacuation planning.

“Sydney is obviously incredibly populated, so we would want to ensure we’re responding in the safest way. In the event of a tsunami emergency, either over-evacuating or under-evacuating the area could be disastrous,” Mr Wilson said.

“This study contributes to the knowledge base that we use in Australia as part of the infrastructure we have in place to protect us from tsunamis.”

Where to from here

As a testament to the team’s investigation, emergency services have already paid close attention to the findings.

Working toward a goal of increasing public awareness around likely effects of earthquake-generated tsunami, the team hope to apply their modelling to the rest of the east coast and even further afield.

“Now we have these results from our work modelling Sydney, we can make an informed assessment that similar estuarine regions would be at comparable risk,” Mr Wilson said.

“We haven’t had the opportunity to model Newcastle yet, as we haven’t been able to access the data. We’d love to map our own backyard as we’d suspect Newcastle would be at a similar risk to Sydney.

“We hope to continue our work to ultimately ensure Australia, and even higher-risk locations overseas, are well equipped to deal with any possible scenario to help keep our communities safe.”

Related news

- Newcastle team on mission to improve childhood cancer outcomes

- Shanae’s passion for caring delivers her dream to work in health

- Food and nutrition degree serves Keren a rewarding career

- Kicking goals on and off the field, Joeli proves you can do it all

- Proving age is just a number, Arlyn wants to inspire more women in their 50s to pursue education

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.