Historians reveal little known histories of the Spanish Flu

Two Centre for 21st Century Humanities historians have delved into different aspects of the Spanish Flu pandemic, revealing little known histories which have become even more pertinent during the COVID-19 crisis.

The 1918-19 pneumonic influenza pandemic, or ‘Spanish Flu’ was the most severe pandemic of the 20th Century. It arrived in Australia in 1918 and about a third of all Australians were infected and nearly 15,000 people died from it. Associate Professor Nancy Cushing and Dr Kate Ariotti were two of five academics to deliver online presentations on the Spanish Flu for the History Council NSW’s ‘The History Effect’ series of seminars.

Nancy’s presentation focused on the scheme of universal inoculation designed to reduce the deadliness of the disease and Kate’s presentation highlighted how the pandemic coincided with the end of the First World War and compounded the devastation of years of fighting.

Protecting People from the Flu: Inoculation

“Australia was unique in having an official national campaign of inoculation which started before the flu arrived,” Nancy said. “Then as now, Australia was fortunate that the Flu arrived on our shores after other countries had already experienced the pandemic and was able to apply lessons they had learned,” she said.

In late November 1918, it was decided that, based on the positive claims for vaccines in reducing the deadliness of the flu, the Commonwealth would pay for citizens to be inoculated with two doses, through a scheme to be delivered by the state governments.

“This was not a compulsory immunisation, like the smallpox vaccine in Victoria had been since the 1850s and people knew that what was being offered was not immunity to the flu,” Nancy said.

Many people did not put themselves forward for inoculation. Cases in which people were inoculated and then contracted the disease were publicised, causing concern.

Others, in their thousands, did roll up their sleeves. Having read about the dreadful effects of the flu overseas, many were keen to do what they could to protect themselves, their families and their livelihoods.

In the busy port of Newcastle, a genuine effort was made to enable as many people as possible to be inoculated.

“Rather than expecting everyone to attend Newcastle Hospital where the vaccines were officially received, immunisation was taken to the people with inoculation depots set up at Council Chambers and children were inoculated en masse at schools.”

Between 2 March and 10 September 1919, 494 deaths were registered as due to influenza or its complications in the Hunter River Health District, from a population of some 50 000 of whom, it was estimated, 40% had contracted the disease. Overall, the death rate was calculated as three times higher for the uninoculated than the inoculated.

“However, when medical scientists reviewed these studies they were less convinced,” Nancy said. “The widespread inoculation program showed that the vaccine was not effective in preventing the flu, although did help to ward off the secondary bacterial infections such as pneumonia which proved lethal in many cases. This helped to advance knowledge of the causation of the flu by challenging the idea that the bacillus was responsible.”

Spanish Flu, Returned Soldiers and Quarantine: Protecting Australia from an Invisible Post-War Enemy

Historian of war and Australian society, Dr Kate Ariotti, detailed how the Spanish Flu reached its peak virulence just as the First World War ended.

She said smaller, more localised outbreaks of influenza had been noted in the British Expeditionary Forces in Europe in May 1918, but in October, in the northern hemisphere autumn, it resurfaced with a vengeance on the Western Front. The very nature and the logistics of fighting the war all allowed for rapid transmission of the virus.

“Crowded conditions in trenches, the movement of soldiers from the frontlines to rest areas where they mingled with civilians, the concentration of sick and wounded in hospitals, the transient populations at military depots and training camps, and lowered resistance caused by (for some) years of fighting meant the virus spread easily.”

“It became a big problem in the Australian Imperial Force—11,700 Australian soldiers on the Western Front were admitted to Field Ambulances suffering from influenza in late 1918,” she said. Even more received treatment for the flu at Base Hospitals.

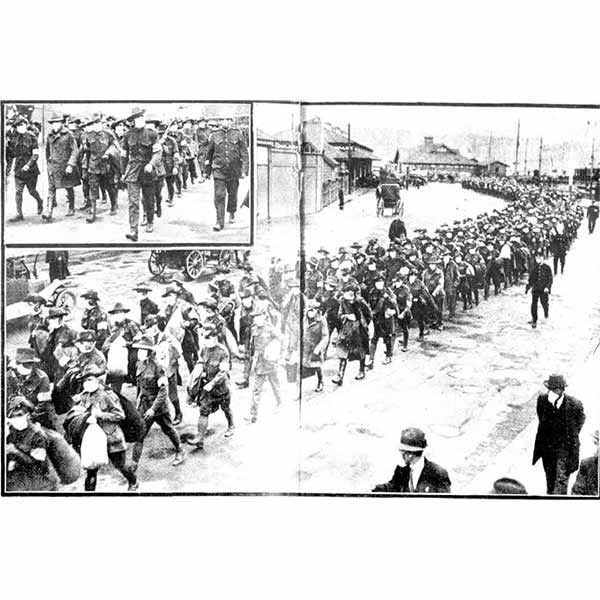

Soldiers returning to Australia after the war were therefore identified as potential carriers of the disease, andhad to follow preventative measures to try and minimise its spread including inoculation and fumigation as well as, importantly, quarantine.

In late 1918, just like today, strict quarantine measures were introduced for people entering into Australia. Many troopships had to sit out at least 7 days of quarantine in Australian ports before the soldiers onboard were cleared for disembarkation. These strict quarantine restrictions were the cause of great frustration for the soldiers and their families.

“After years of war the former soldiers were, as the Sydney Daily Telegraph put it, ‘looking forward to a glorious time as soon as they touched Australia.’ But quarantine—and other ‘social distancing’ restrictions on the gathering of people in public places, which included the cancelling of parties for returned servicemen—delayed these ‘glorious’ home-comings,” Kate said.

Frustrations came to a head in one incident in February 1919 when the Argyllshire, carrying over 1000 soldiers returning from the war, was forced to extend its quarantine in Sydney harbour when a suspected case of the flu was found on board. Around 40-50 fed-up soldiers decided to escape the quarantined ship, with some even making it home by train to Cooks Hill and Maitland.

“Despite the strict quarantine measures, hundreds of thousands of Australians contracted Spanish Flu, and an estimated 12-15,000 Australians died from the disease. Though these figures represent far fewer casualties than in other parts of the world, the flu crisis was a devastating blow to a country already reeling from the loss of 60,000 soldiers and the traumatic social, economic and political upheaval caused by the war,” Kate concluded.

Related news

- Newcastle team on mission to improve childhood cancer outcomes

- Shanae’s passion for caring delivers her dream to work in health

- Food and nutrition degree serves Keren a rewarding career

- Kicking goals on and off the field, Joeli proves you can do it all

- Proving age is just a number, Arlyn wants to inspire more women in their 50s to pursue education

The University of Newcastle acknowledges the traditional custodians of the lands within our footprint areas: Awabakal, Darkinjung, Biripai, Worimi, Wonnarua, and Eora Nations. We also pay respect to the wisdom of our Elders past and present.